Fiery Glacier Wars

Seething debates and torched reputations laid the foundations for glaciology

Blast from the Past

Last week, the quaint Swiss village of Blatten was happily perched amid the snow-dusted Alps. Then, in a sudden and terrifying turn, a glacier collapsed right on top of it, pretty much wiping it off the map.

Fortunately, just before the catastrophe the local government evacuated the 300 residents from the hamlet; even cows were airlifted out.

Unfortunately, this won’t be the last time we see such horror. Record-breaking temperatures are melting glaciers at unprecedented rates, causing landslides, floods, and, well, collapsing glaciers that obliterate whatever’s below.

According to Swiss media, Alpine glaciers have shrunk in volume by about 60% since 1850—but most of that shrinkage occurred in the past 25 years.

Reading about Blatten’s cruel fate got me thinking about a different kind of glacial destruction—one that started 20 miles to the northeast of that village but played out not in ice but in scientific journals, the popular press, and academia. It involved the ground-breaking Swiss geologist Louis Agassiz, the Irish physicist John Tyndall, and the eminent Scottish professor James David Forbes whose vicious scientific feud ended with a career—and a life—crushed as thoroughly as Blatten itself.

A Radical Idea

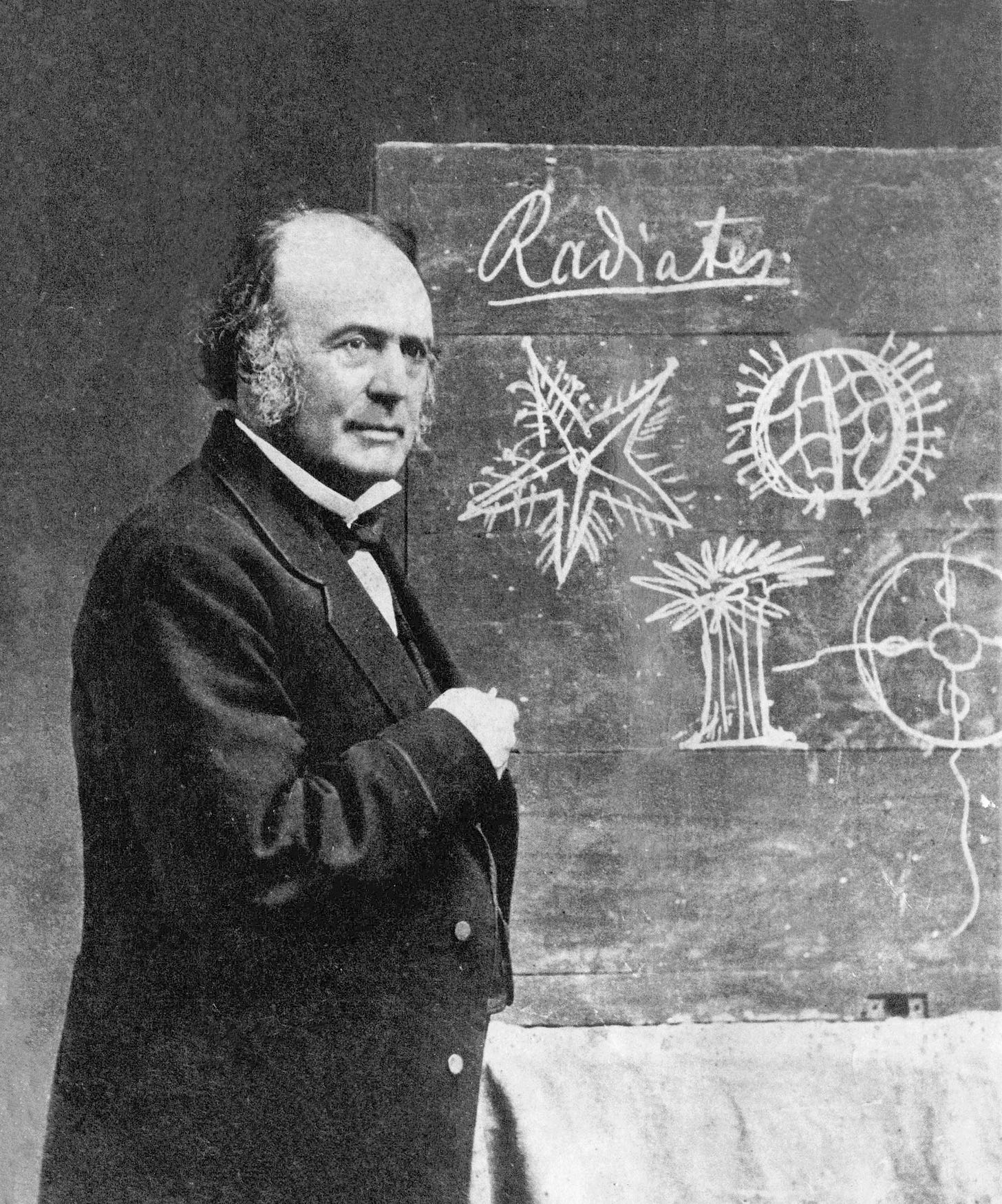

It all started in 1837, an era when glaciers were still mostly feared and climbing them was just coming into vogue. Agassiz, a big, burly naturalist praised for his work on fossils, stood before the Swiss Society for Natural Science that July, ostensibly to lecture about fossilized fish. Instead, in a booming voice, Agassiz announced he now agreed with a fringe idea: a vast ice sheet had once covered the Alps, scraping out valleys and gouging terrain in its slow passage.

The response from his scientific colleagues: cries of horror, howls of disdain. Most Western thinkers at the time believed that a great flood — probably Noah’s — had been the force that sculpted Earth.

To be fair, floods did shape parts of the world, such as the Mediterranean and parts of the Pacific Northwest. But tectonic forces and glaciers were much bigger players planet-wide.

While Agassiz wasn’t the first to suggest glacial expansion—Goethe, for instance, thought only glaciers could explain “erratic” boulders found far from their origin—Agassiz went further.

In 1840, he published Studies of Glaciers, arguing that much of the planet had once been buried under vast ice sheets.

“Never did an idea make a more profound disturbance in the scientific world,” wrote Henry Smith Williams in A History of Science. Scientists responded with “ridicule, contempt, and rage.” Even his mentor, the famous naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, recommended that he promptly drop his silly glacial ideas and go back to fish.

But Agassiz pushed on.

Planting Seeds Further Afield

Seeking more geologic proof—and converts—Agassiz took his glacial gospel to the UK, claiming even Scotland had once been ice-covered. Most scoffed. But a few listened.

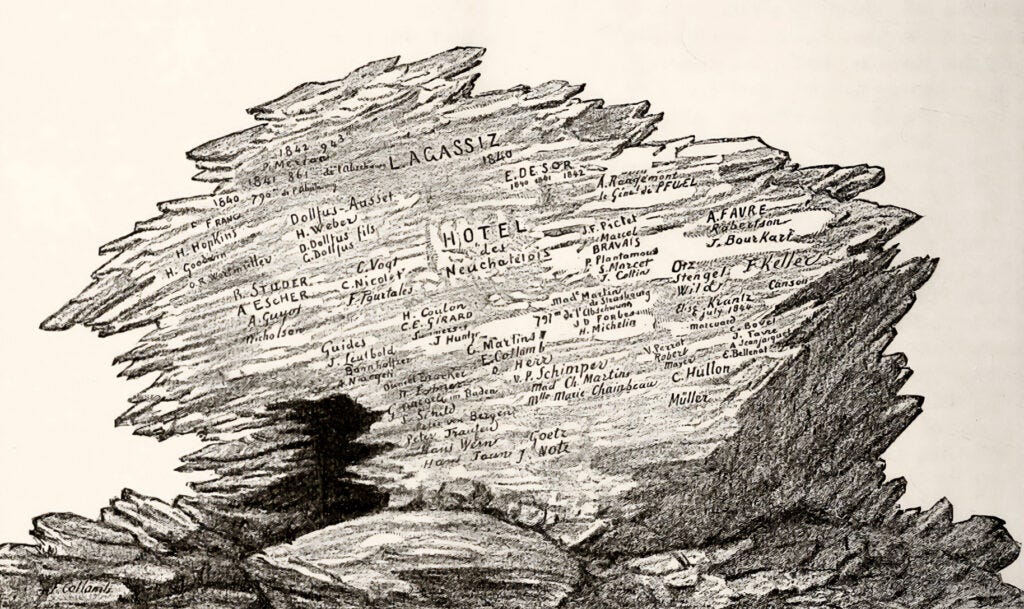

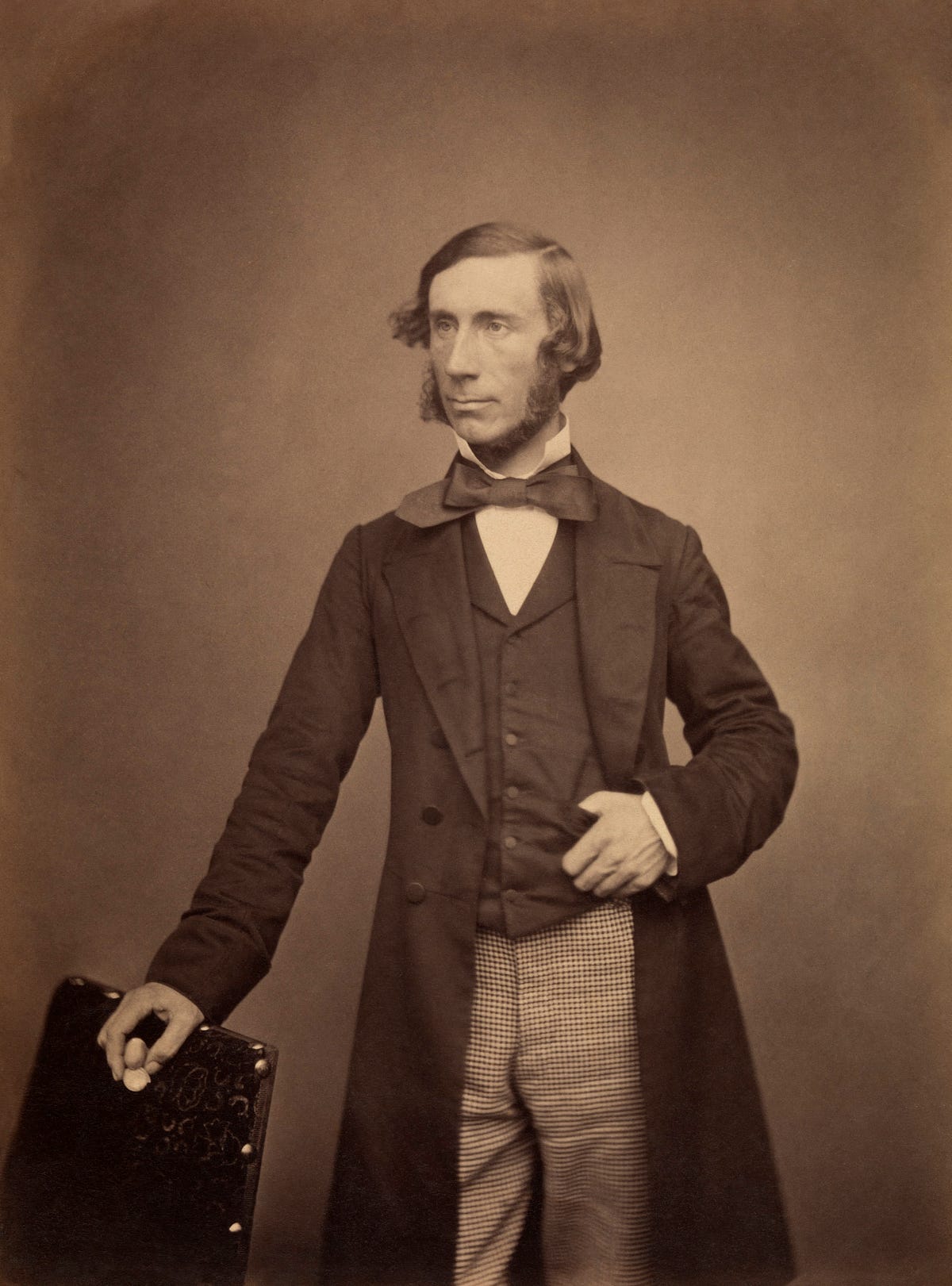

Among them was Scottish physicist James David Forbes, known for his work on heat conductivity and earthquakes. He accepted Agassiz’s offer to visit Switzerland and inspect the Unteraar Glacier firsthand.

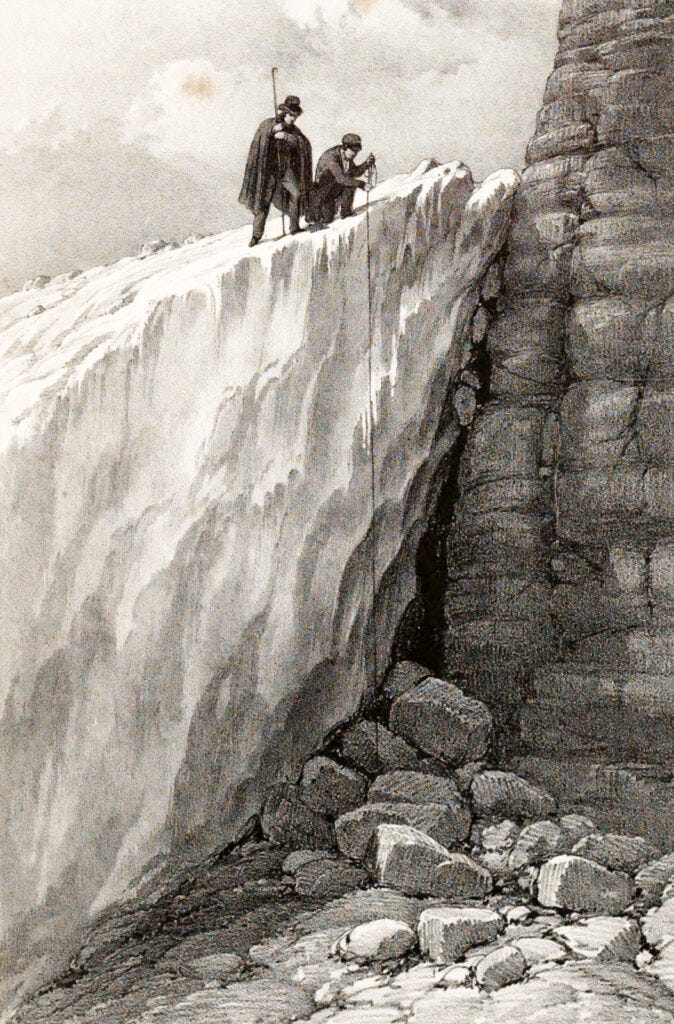

In 1841, just getting to the Alps was a feat—and once Forbes finally arrived he discovered that Agassiz’s so-called “Hôtel des Neuchâtelois” was actually a crude shelter of boulders wedged between two glaciers. Nevertheless, the Scotsman was thrilled, spending the month of August with Agassiz climbing across the glaciers, measuring anything that could be measured, and studying the icy behemoths close up.

Not only did Forbes become a convert to Agassiz’s ice age idea, he made some important discoveries himself—discoveries that would bolster glaciology and result in his demise.

Peering down into a crevasse, Forbes discerned twisted vertical bands in the ice, glistening blue. When he pointed them out to Agassiz, the Swiss scientist dismissed them, saying he’d never seen them before, sand must have fallen in quite recently. But when Forbes encountered more of the curving striations in other crevasses, he postulated that they were caused by glacial movement—that the glacier was actually viscous and folding in on itself as it traveled.

Forbes summed up his glacier theory, writing “A glacier is an imperfect fluid or viscous body which is urged down slopes of a certain inclination by the mutual pressure of its parts.”

Agassiz pooh-poohed the idea, downplaying the significance of the blue bands.

However, two months later Agassiz wrote to Alexander von Humboldt claiming he’d made an important discovery—twisting blue striations running down through glaciers—and mentioning nothing of Forbes. When the letter to von Humboldt was published, Forbes was shocked.

So Forbes wrote about the blue bands in a scientific journal and a book, Travels through the Alps of Savoy—adding that despite two years of intensely studying the glacier previously, Agassiz somehow had never noticed the striations until Forbes pointed them out.

The Swiss scientist was incensed.

Agassiz struck back, sending out 10-page letters to 500 geologists, naturalists, and other big names in science, claiming that actually he’d known about the blue bands before—Forbes hadn’t “discovered” them at all; Agassiz claimed that Forbes knew he’d planned to write about them, and Forbes wasn’t giving due credit. What’s more, he insinuated that Forbes was an arrogant know-it-all, and said he’d driven Agassiz and his team bonkers during his month-long stay in the shelter.

According to his biographer Christoph Irmscher, Agassiz was often “accused of appropriating other people’s ideas or observations.”

To Forbes’ chagrin, Agassiz kept up the ruse and kept slamming him—and by then the Swiss scientist’s stature was growing: his “ice age” idea drew more big-name converts—and Harvard hired him as a professor of natural science. Louis Agassiz was suddenly a rock star, giving well-attended public lectures, starting a Harvard science museum, writing for The Atlantic, and being besieged by fans when he went out.

Forbes’ until-then glistening reputation was already in question when Irish scientist John Tyndall jumped in, for some reason gunning for the Scotsman, whose work on other matters he’d also viciously attacked.

Beyond the historic tensions between the Irish and Scottish, Tyndall’s antipathy to Forbes may have been rooted in Forbes’ religious devotion, a quality Tyndall disapproved of in scientists.

In 1859, the week before Forbes was due to win an award from the Royal Society, Tyndall made a bogus claim that Forbes had plagiarized the work of recently deceased glaciologist Louis Rendu—an accusation that Rendu had never made while alive. Unable to disprove the allegation before the awards ceremony, the society at the last minute awarded someone else.

What’s more, Tyndall smashed up Forbes’ theory about glacial plasticity and movement. Glaciers cracked and refroze, announced Tyndall—that was the force that propelled their movement, end of story. He mocked Forbes and his ideas about glaciers’ viscosity privately, in print, and in public speeches at scientific societies, reveling in his attacks. In Tyndall’s book, Glaciers of the Alps, he slammed Forbes’ theories, repeatedly gave others credit for Forbes’ ideas, and kept falsely implying Forbes was a plagiarist.

Tyndall bragged in a letter that he “so utterly annihilated” Forbes’ viscosity theory “that its author will hardly acknowledge it.” A friend wrote back heartily agreeing, saying Tyndall had “run an oiled rapier” through Forbes.

Poor Forbes, who continually maintained that his theory and Tyndall’s were complementary, would have agreed. The attacks, which Tyndall kept up, made a nervous wreck out of sensitive Forbes. Previously fit, he grew weak, falling suddenly ill, and becoming terribly depressed.

‘‘For about three years,” Forbes wrote to one of his remaining scientific allies in 1864, “I have felt disheartened and hopeless as to stemming the popular tide of propositions against my Theory of Glaciers—or I should say against me personally as its author.” He never recovered from it.

As Alfred Wills, the friend at whose house Forbes passed away in 1868, wrote of the matter, “He fell into hopeless difficulty and embarrassment, which so preyed on his sensitive and remorseful nature that he literally died of a broken heart at age 54.”

Obituary writers were so confused about his accomplishments that Tyndall had so thoroughly clouded, that they essentially wrote that Forbes did some work on glaciers, but they weren’t sure what they meant.

Even then Tyndall wouldn’t let up, for years bashing the dead man as a fool, falsely accusing him of plagiarism, and leaving Forbes’ legacy in tatters.

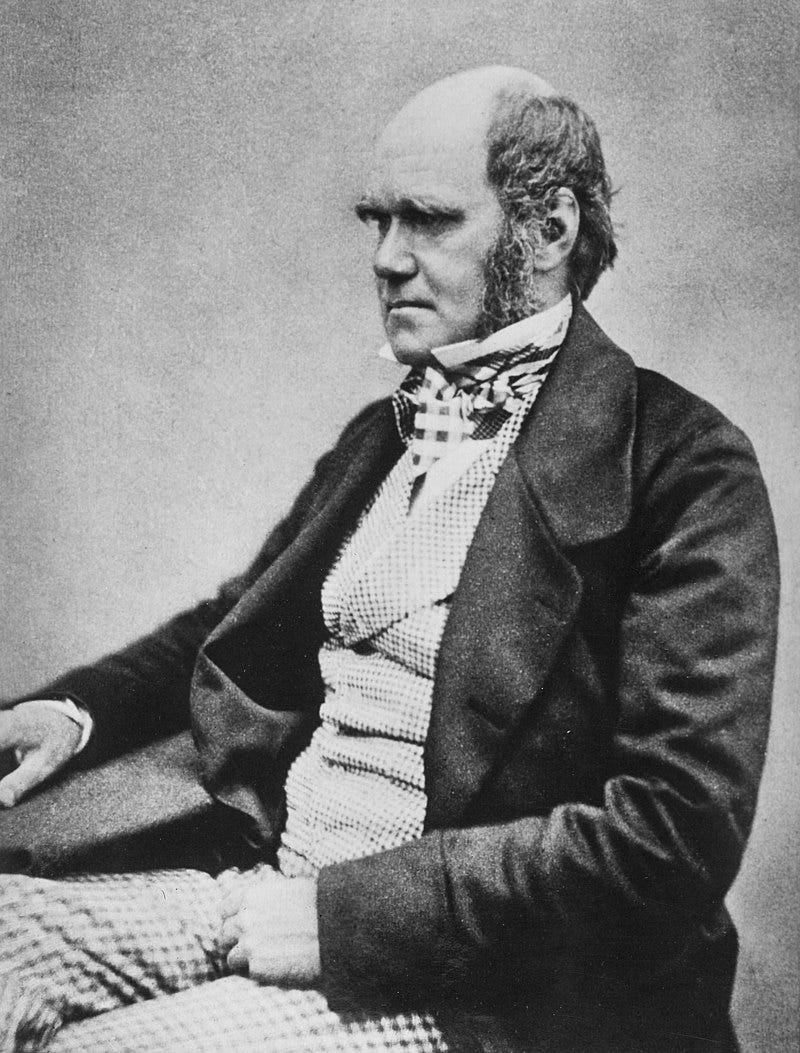

While Tyndall was busy erasing Forbes’ contributions, Agassiz—now the most influential scientist in the U.S.—had a bigger fish to fillet: Charles Darwin.

Agassiz v. Darwin

Agassiz—who’d become obsessed with his research on turtles and jellyfish— originally began on friendly terms with Darwin, corresponding with the English scientist, even sending him barnacles for study. But in 1859 when Darwin published his theory of evolution and ideas on natural selection and adaption to environments, Agassiz was aghast.

A creationist, Agassiz believed that all species had been perfectly formed by God, didn’t change, and didn’t travel from their original site of creation. He appeared such a barrier to consideration of Darwin’s revolutionary ideas that Darwin had to figure out a means to sidestep Agassiz. His method: he courted Agassiz’s colleague, the esteemed Harvard botanist Asa Gray, who by then was totally sick of the Swiss windbag, and annoyed that Agassiz kept framing science from a biblical perspective.

As noted on History Cambridge, Gray wrote a review of Darwin’s Origin of Species in the Atlantic in July 1860, “providing a pivotal victory for Darwin: It gave his highly controversial theory, which he had published the previous December, the support of one of America’s most respected scientists.” Gray proved a crucial American advocate for Darwin; in 1860, he publicly debated Agassiz on three occasions, each time winning, coolly ripping apart Agassiz’s arguments against evolution and natural selection.

Shortly thereafter, former supporters and fans started ditching Agassiz, whose ideas—outside of his Ice Age theory—appeared washed up.

So despite his great influence on American science, the Swiss-born scientist got his karmic takedown, going down as a has-been when he died in 1873.

Of the trio, only the reputation of Tyndall remained sterling (well, if you overlooked his cruelty), when he passed away in 1893—but his ideas on ice would eventually be smashed up, too.

The Final Tally

While Agassiz was correct about the ice age, he erred in the extent of land that was once glacier-covered and how quickly the ice age arrived—he’d said it happened overnight.

Forbes was correct that glaciers are viscous and move due to their internal pressure, but he didn’t factor in their cracking, refreezing, and the effects of meltwater and slippage.

And Tyndall’s ideas about cracking and refreezing were correct when the icy masses push through narrow passages, but Forbes’ fluid model better describes the majority of glacial movement. Modern glaciology holds that Tyndall’s ideas were in fact complementary to those of Forbes—just as Forbes maintained all along.

Yet, despite all the fury and the attacks, like some massive glacier the passage of time has crushed the accomplishments and mostly eroded the names of these hugely important scientists from societal memory. The only one who still holds name-brand recognition is Charles Darwin, who wisely sidestepped the glacier controversy altogether.

Science has walked a long way to ditch religion as the fairy tale that it is. Moreover, the academic world is full of these stupid feuds because money and prestige play a big role in financing these studies. I am concerned about the melting of glaciers and the Siberian permafrost as well for the viruses and bacteria frozen since 400K years ago. In August 2016, a teen died, and dozens were hospitalised due to an outbreak of anthrax released by the thawing of a layer of permafrost on which a reindeer carcass was lying. So many viruses that have plagued humanity throughout its history lie dormant in this frozen stratum.