Founding Frenemies: A Fourth of July Tale

The 50th anniversary of signing the Declaration of Independence marked a very big day for two founding fathers

A Happy Revolutionary Beginning

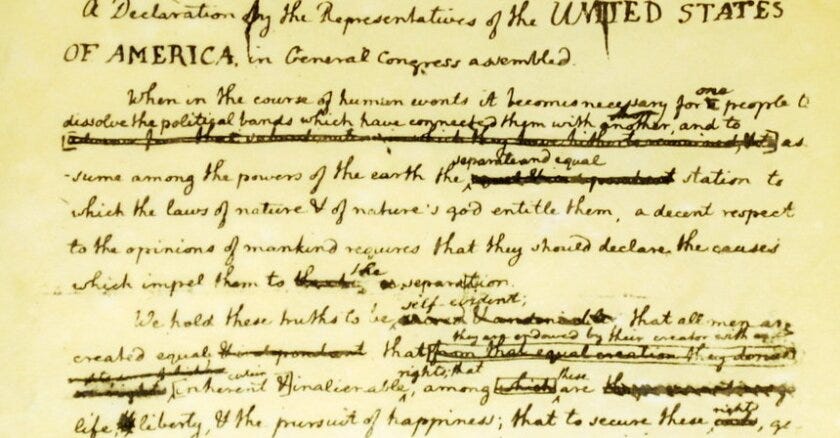

Meeting in 1775 at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia and John Adams of Massachusetts originally thought the world of each other. Both were members of the committee to draft the Declaration of Independence, and each thought the other should write it.

Adams, however, insisted that the responsibility fall to the Virginian because, as Adams noted to Jefferson, “I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very much otherwise.” Besides, Adams added, Jefferson was a far better writer.

But not long after the ink had dried on the document that formed a new republic on July 4, 1776, the two founding fathers began to clash, their ideologies turning them into bitter foes. Adams, who signed up with the Federalist Party, favored a strong federal government and presidency, while Jefferson wanted more power vested in the states — in part due to his vision of agrarian independence, but also reflecting his personal stake in a slaveholding economy, unlike the more anti-slavery Adams.

The Friendships Frays Further

During Washington’s second term, Adams supported the Jay Treaty of 1794, which smoothed over remaining issues with the British and encouraged more trade with the former foe. Jefferson vehemently opposed it.

Jefferson wrote a letter to Italian wine maker Filippo Mazzei, slamming the Federalists and portraying them essentially as foot kissers to the British. When Mazzei sent the so-called “Mazzei Letter” to a publisher and it was eventually published in New York, it became a source of huge controversy and humiliation for Jefferson.

Their rivalry turned more dramatic when both Adams and Jefferson were running for president in 1796 — an election Adams won — and Jefferson, who received the second-most votes, became his vice-president, despite being of a different party.

Their relationship was icy: Adams sidelined him, all the more when Jefferson bad-mouthed Adams for signing The Alien and Sedition Acts.

The Alien Act gave the president the right to eject any foreigner believed dangerous, while the Sedition Act prohibited scandalous and malicious writing against the president and US government. Even though it violated the freedom of speech guaranteed by the First Amendment, the act allowed Adams’ critics to be rounded up.

Among those jailed: James Callender, publisher of the Richmond Examiner — an anti-Adams newspaper that Jefferson just happened to be secretly bankrolling.

Incendiary Attacks

Until he was put behind bars, Callender had been going hog wild in his attacks on Adams, writing that he was a “repulsive pedant” and "hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman” in between intimating that Adams wanted to wear a crown. While he painted Adams as a “gross hypocrite” and “egregious fool,” he fawned over Jefferson, calling him “an ornament to human nature.”

In 1800, Adams and Jefferson again vied for the presidency and the mud-slinging only grow more intense — with Federalist newspapers painting Jefferson as an untrustworthy atheist who wanted to torch the Constitution.

When Jefferson won — promptly pardoning Callender, who went back to his newspaper — Adams criticized him on everything from downsizing the navy to his naivete and huge ambition, though his sharpest barbs were in private letters. “I shudder at the calamities, which I fear his conduct is preparing for his country,” Adams wrote in 1804 as Jefferson was gearing up for his second term.

Kissy-Kissy, Nicey-Nice, and An Irony

Finally, not long after Jefferson stepped down as president in 1809, Benjamin Rush, another founding father, got the two ex-presidents to give their hostilities a rest and rekindle their friendship. Their letters, sometimes witty and sometimes philosophical, would continue for the rest of their lives.

However, July 4, 1826 — the 50th anniversary of their signing of the Declaration of Independence — proved momentous for both. At his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, Adams died, just after uttering "Thomas Jefferson still survives.” But in fact, unknown to Adams, his frenemy Jefferson had passed away earlier that same day — about six hours before.

I guess as someone who is also obnoxious, suspected and unpopular, I'd have to choose Adams, but glad I wasn't old enough to vote in 1800.

Thomas Jefferson was heavily influenced by the Enlightenment, the subsequent French Revolution, and Napoleon. While John Adams was worried that the American experiment would fail if radicals and opportunists took control and replicated another Reign of Terror with guillotines working at full speed. Hence, they drifted apart to become political adversaries.

Moreover, the brutal 80% mortality of the first settlers in the Tobacco Coast due to contaminated water, famine, and conflicts with Native Americans was the main reason to resort to the use of African slaves, which was undoubtedly immoral, but it played a crucial role in the progressive enrichment of the Southern colonies. And without the immense riches of tobacco and also cotton which they produced heroes like George Washington and also the financier genius Robert Morris, I guess the Declaration of Independence would have been drafted fifty years later and after crushing defeats.