How mattresses, mysticism, and mesmerism saved Buddhism

A Russian, an American, and a love of comfy beds worked together to revive an ancient faith at a very shaky moment

Young Buddhist monks in Sri Lankan temple. (Photo: Melissa Rossi)

Buddhism, originally an Eastern religion, has become trendy in the West. It’s slipped into the mainstream, with concepts like “nirvana” and “mindfulness” now part of the common vernacular, and meditation is practiced everywhere from grade schools to prisons. A deeper appreciation of the faith, one of the world’s major religions with more than 500 million adherents, is evident: The Metropolitan Museum’s just-opened exhibit of ancient Buddhist art, in New York, is garnering rave reviews, with the Washington Post critic, for one, calling it “spellbinding” and “inexpressibly moving.”

But most people don’t connect today’s popularity of Buddhism with a swirling-eyed Russian mystic or an American journalist with a long snowy-white beard, and most people entirely miss the connection between Buddhism’s spread and the British fondness for comfortable beds, for that matter.

However, in an odd twist, the eerie spiritualist Madame Helena Blavatsky, the New York reporter Colonel Henry Steel Olcott, and a furniture store in Sri Lanka all played crucial parts in keeping Buddhism from extinction in South Asia, its birthplace, as well as boosting its spread across the planet.

Blavatsky (1831-91) and Olcott (1832-1907) revived Buddhism in South Asia. (Wikipedia)

Based on the teachings of wandering prince-turned-seeker Siddhartha Gautana, who achieved enlightenment after meditating under a Bodhi tree for 49 days, Buddhism originated in India in the 5th century BC. It focuses on avoiding suffering and disentangling from the desires of the physical plane. Sharing some concepts with Hinduism, such as reincarnation, Buddhism nevertheless played second fiddle to Hinduism on the subcontinent.

However, in modern-day Sri Lanka, the tear-shaped island to India’s southeast, the religion took root and the land became Buddhism’s spiritual heart.

On the island then known as Ceylon, the religion’s first holy book, the Pāli Canon, was penned, and likenesses of Buddha are chiseled into mountain faces, painted in grottoes, and spectacularly carved into giant sculptures.

Local lore has it that Buddha himself, who’d visited several times, had predicted this spiritually-charged island would be the place where his illuminating ideas would most brightly shine. And for millennia Buddhism thrived in this spice-rich land, where rivers once glittered with precious gems and statues of the Buddha still rise from mountain peaks and hide away deep in the jungle.

But colonial powers sought to change that.

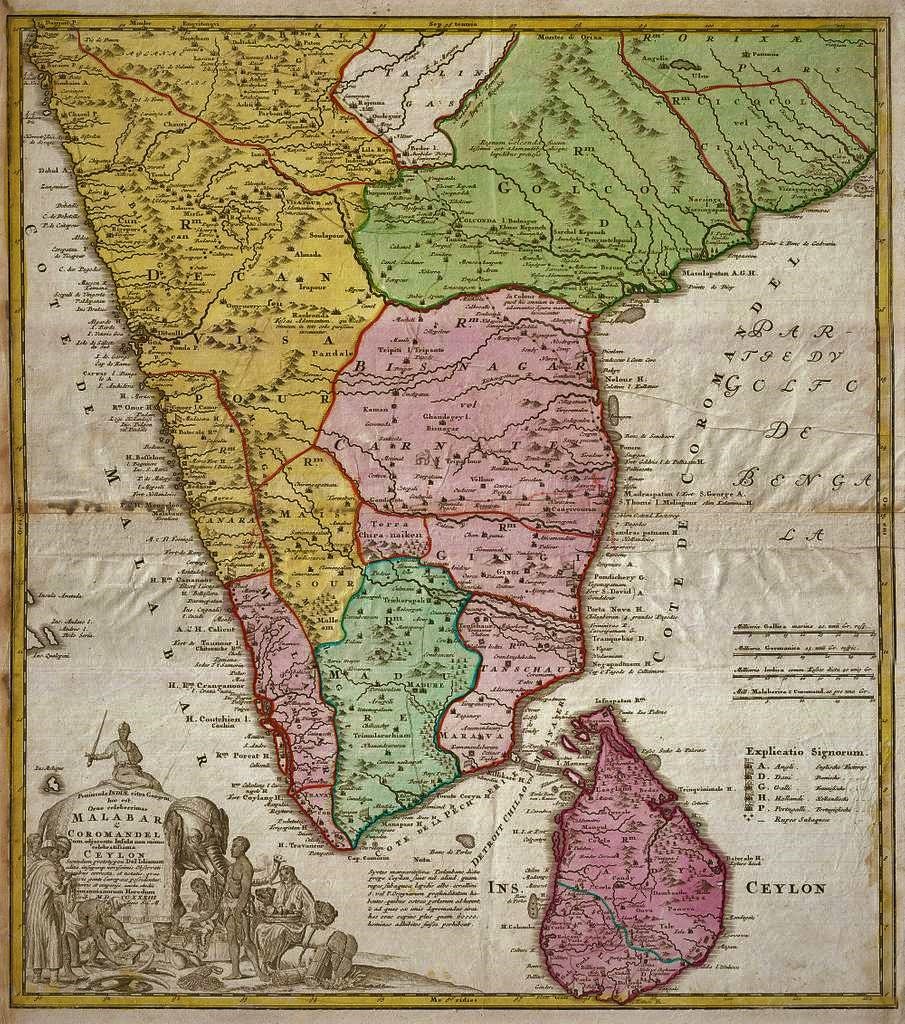

1733 map of South Asia, showing part of India, and Ceylon to the southeast. (Map by Hormann Heirs via Wikimedia Commons)

Starting in the 1500s, the Portuguese, then the Dutch, and finally the British who claimed this tea-rich isle tried to convert locals to Christianity. And little by little, it worked. By the late 1800s, Buddhism was teetering at near-extinction on Ceylon, particularly after the British colonial government discouraged locals from providing monks with the alms from which they survived and also banned monks from their long-held posts as teachers, instead filling local schools with Christian missionaries.

However, the colonial Brits had a weakness, an expensive one. They loved their imported iron beds with spring mattresses — and their purchases made local furniture store owner, Don Carolis Hewavitarana, quite rich.

As one of the few locals who had remained a Buddhist, Hewavitarana fought back against the Christianization of his homeland, funding assorted endeavors to resuscitate the dying religion — including staging public debates between monks and missionaries, debates which the monks invariably won. Nevertheless, his efforts appeared for naught, and Buddhism in Ceylon continued dangling by a thread.

Until Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott showed up.

A fascination with spiritualism had brought the Russian and the American together a few years before, in 1875: A New York newspaper had dispatched Colonel Olcott — who was also a lawyer specializing in fraud — to the Eddy Farmhouse in Vermont, where reports of seances, table rappings and messages from the dead had New York society intrigued. Sent there to debunk the happenings, Olcott instead was entirely fascinated by Madame Blavatsky, a world-traveling medium famous for levitation and talking with ghosts, whom he did not view as a huckster. They returned to New York together and founded the Theosophical Society — dedicated to bringing the wisdom of the East to the West.

With plans of expanding their Theosophical Society worldwide, the colonel and the mystic sailed to India in 1880, promptly reading news reports of the battle to keep Buddhism alive on Ceylon. So they wrote to the furniture store owner, announcing that they were coming.

Buddha himself might not have received a more enthusiastic arrival on Ceylon, where local VIPs, especially the few who were still Buddhist, looked upon Olcott and Blavatsky as potential saviors: the foreigners were feted like gods and shown the island’s holy treasures, among them the yellow “tooth relic” from the ancient kingdom of Kandy; when asked to use her psychic powers to discern if the tooth had indeed been Buddha’s, as was claimed, the madame mystic diplomatically replied that of course it was — back when Buddha was incarnated as a tiger.

Both Olcott and Blavatsky promptly converted to Buddhism, becoming awe-struck as they traveled the country to sacred sites. They were so stirred that Olcott — scarcely an expert in the religion — gave an impassioned speech the next night in Colombo, the island’s capital city. And that was how the furniture man’s son — David Hewavitharana — would first get the idea to save Buddhism on a global scale.

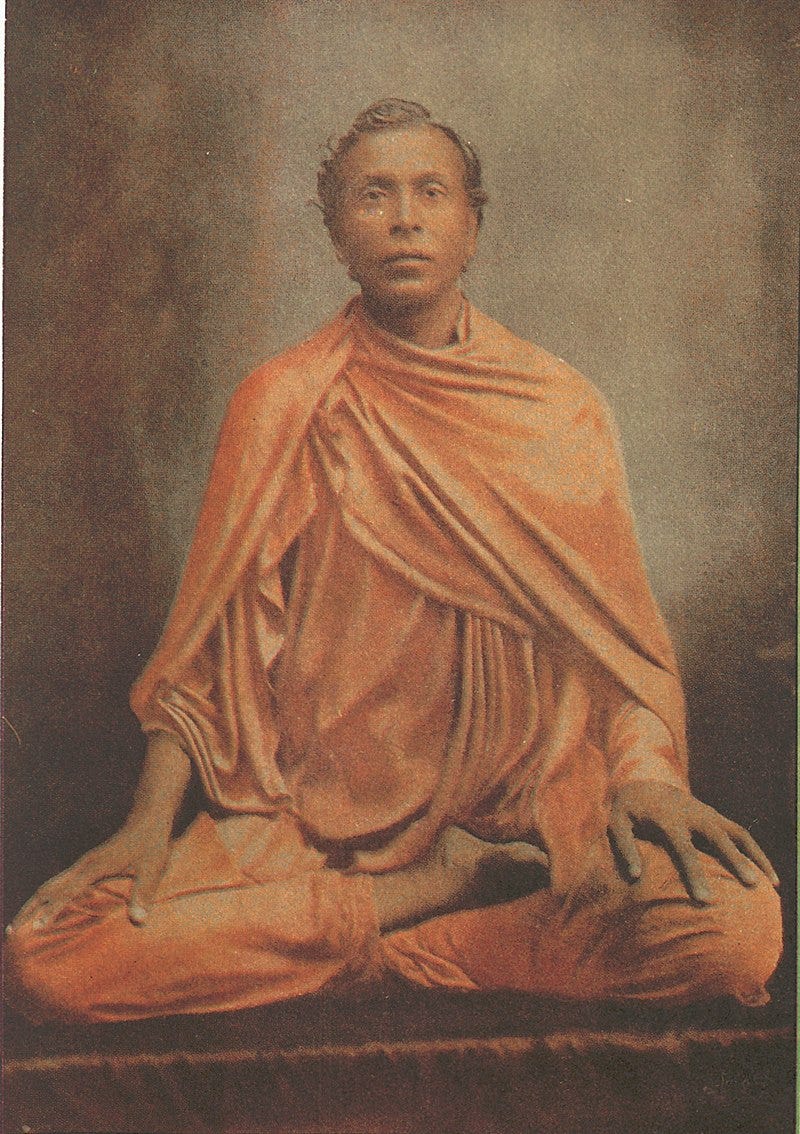

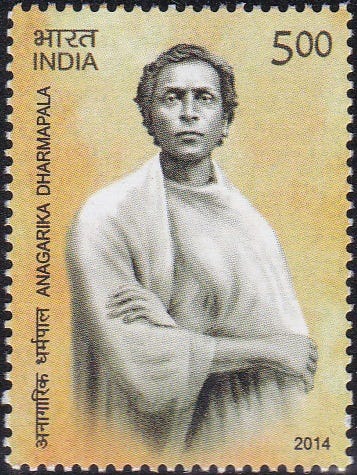

Son of a wealthy furniture maker, David Hewavitharana (1864-1933) is considered the first global Buddhist missionary. His fund-raising abilities helped bring Buddhism to far corners. (Wikipedia)

With an early philosophical bent that reflected in his soulful eyes, David was only sixteen when he took in Olcott’s initial speech, a life-changing event that marked the first time he’d heard an English speaker extol his religion; his British teachers had mocked and condemned it.

Buddha, said Olcott, “found that the pleasures of the eye, the ear, the taste, touch, and smell are fleeting and deceptive: he who gives value to them brings only disappointment and bitter sorrow upon himself. The social differences between men he found were equally arbitrary and illusive; castes bred hatred and selfishness; riches [created] strife, envy, and malice. So in founding his faith, he laid the bottom of its foundation-stones upon all this worldly dirt, and its dome in the clear serene of the world of Spirit.”

Beyond applauding Buddhism for attempting universal connectedness by stripping away desire and vice, however, Olcott spoke of how humans across the planet were inherently linked in a universal reality, and how spirits could communicate across time and space. The audience was stunned and stupefied at his words, so much so that when the speech wound up, nobody clapped. Ceylon was steeped in magic and folklore — so-called “devil dancers” were still summoned to drive away spirits that caused illness, and horoscopes were cast on special palm leaves — but nobody had spoken of philosophy and cosmology in such poetic, flowery terms.

Young David, then 16, was enthralled. These foreigners — the bearded American, a Civil War veteran, so earnest in his search for world unity and divining the secrets that would catapult humanity into higher consciousness, and the electrifying Russian in babushka scarf around whom objects appeared and disappeared — jolted his world, their arrival making previous plans of taking over his father’s furniture store now appear an empty exercise in the worldly and vain.

Olcott opened the Buddhist Theosophical Society in the island’s capital Colombo and gave stirring lectures as he traveled from village to village, fund-raising to build new Buddhist schools where monks would again be teachers. He lobbied the British officials, finally convincing them to make official holidays of Buddhist holy days and to lighten up on their treatment of monks. With a Buddhist revival apparently well underway, Olcott — by then known as the White Buddhist — set off traveling for a year.

Upon returning, he was chagrined to find that the Buddhist revival on Ceylon had fizzled out. The Theosophical Society had withered, already forgotten, few had delivered on the money they’d pledged, and schools weren’t being built.

Olcott set out again lecturing across the island — this time with David, who served as translator — the two traveling in a fancy two-story carriage that in itself generated awe. This time Olcott added a new twist: to stoke interest in the religion, he claimed he could heal — channeling the holiness of Buddha — and he worked his magic by employing his skills as a hypnotist.

His traveling show, more than anything else, proved to be the needed spark to reignite a fervor for Buddha’s teachings on Ceylon. David crisscrossed the countryside many times in Olcott’s two-story cart, astounded by the showman’s effects, as he witnessed former Christians converting to Buddhism in numbers not seen in centuries.

As new Buddhist schools by the hundreds began shooting up across Ceylon, Olcott himself wrote the needed Buddhist textbooks — catechisms that would soon be printed worldwide.

Thanks to the Buddhist schools that Olcott helped build, Ceylon’s Buddhist flag that Olcott helped design, and the Buddhist calendar with Olcott-designated holidays — not to mention his Buddhist Theosophical Society and his frequent lectures — Buddhism had once again taken root on Ceylon.

But Blavatsky helped it grow further.

As much as Olcott influenced young David, Madame Blavatsky exerted more of a magnetic pull. Over protests from his parents, David ran off to study with the occultist in India, where Buddhism was almost forgotten.

In between falling into trances, when she spoke with “the Invisible Masters” — evolved ghosts transmitting their thoughts from the Himalayan mountains, she claimed — Blavatsky impressed in David the need to learn Pali, the lost language of Buddhism, once widely spoken on Ceylon.

While in India, she also took him to the fabled Bodhi tree under which Buddha had found spiritual enlightenment. David was horrified to find the temple vandalized, falling apart, and now a Hindu shrine. He vowed to restore the temple and place it under Buddhist care, becoming famous for starting a foundation to do it — and for reviving the religion in India, where it had been dead for over a thousand years.

Bodhi Tree temple in India (Photo: Ken Wieland via Wikipedia)

Immersed in Buddhist texts, meditations, and studies with Blavatsky, David grew ever more impassioned, ultimately donning monk’s garb and taking a new name, Anagarika Dharmapala — which means “homeless defender of Buddhist ideals.”

The Buddhism that Anagarika Dharmapala promoted to the world was shaped by Olcott and Blavatsky, whose views, lectures, and writings weren’t entirely traditional. Emphasizing meditation and giving as much power to individuals as monks, the somewhat modified religion was widely popularized by Dharmapala during his visits to far corners of the world as the “first global Buddhist missionary,” as he is called during his trips across Asia, Europe, and the US. He reinvigorated the religion, attracting new followers, wherever he stepped foot.

He met with the Princess of Siam (now Thailand) and the emperor of Japan, he bonded with the Buddhist leaders in Burma. He lectured at the prestigious Conference of World Religions in Chicago in 1893, standing out not only because he was dressed entirely in white, while most other attendees wore robes of black, but because the 29-year-old speaker was so handsome and extremely persuasive.

Before returning to Ceylon to start a Buddhist newspaper, Dharmapala visited Hawaii, meeting Mary Robinson Foster, a wealthy American living in Honolulu, 49, and recently widowed. Foster quickly became so enamored of the man and the religion he touted, that she built the first Buddhist temple in Hawaii and became his lifelong patron, funding whatever projects he suggested, writing out checks for $100,000 here, $300,000 there for the next 40 years.

Those checks funded new hospitals and schools on Ceylon, helped with his newspaper and foundation, and also paid for the transformation of the land holding the bodhi tree in India, where Buddha first saw the light, into a temple that is now a Buddhist pilgrimage site.

Gaining independence from the British in 1948, Ceylon changed its name to Sri Lanka. Buddhists remain the majority on the island, which now boasts statues of both Olcott and Dharmapala, the men who replanted the religion on the isle long ago picked by Buddha as a land where his ideas would thrive.

This a very illuminating piece you just wrote. I misguidedly thought this particular religion always had a certain degree of popularity, and the ease of travel was responsible for that '60s era when Oriental teachings became widely known. I always loved that Buddhist notion of extreme frugality that has been with me during tough times.