How the top hat kept Afghanistan in the dark: PART ONE

A deep dive into newspaper reports from 1928 reveals a startling story about the first attempt at modernizing the change-resistant Central Asian country.

With the three-year anniversary of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan fast upon us — and the whip-cracking Taliban back in power, girls over age 10 no longer attending school, and women forced back into burkas — it’s clear that Western attempts to permanently yank the Islamic and tribal country into the 21st century have spectacularly failed.

But while fingers point at any number of Western officials for Afghanistan’s return to the past, they should be pointing at the silk top hat.

Because when trunks of European top hats first arrived in Afghanistan 95 years ago, along with an edict to wear them, they brought a screeching halt to a vast modernization scheme, which until 1928 had been chugging along.

The failure of that 1928 plan was so resounding that it set Afghanistan on an anti-progress course that it’s never veered from for long. And, unlike later attempts at reform, these original plans to bring Afghanistan out of the dark and into the present came from within — being the ideas of Afghan king Amanullah Khan.

If only he’d sidestepped the issue of headgear and clothes, the country could have a solid foot in modernity by now.

The 1928 decree to trade in turbans and Pashtun caps for fancy silk hats standing six inches high was only the latest demand of King Amanullah, then 35. He was respected for bringing independence to his country after the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919, but he’d been acting peculiarly since his recent tour of Europe.

The stout monarch with dark inquisitive eyes and neatly trimmed mustache was a progressive, especially for Afghanistan. His grandfather was fond of shooting foes out of cannons, but King Amanullah wrote a new constitution banning torture, slavery, and child marriage, and he championed women’s rights, not a popular cause among Afghanistan’s Muslim preachers, who also didn’t like him opening schools for girls. He was, they thought, getting too many ideas from the infidel-ridden West.

Before he’d even set out on his grand European tour, the country’s mullahs were already stewing about what to do about Amanullah’s latest symbol of Westernization: Kabul’s new movie theatre, Afghanistan’s first, and just one of the king’s introduced novelties that they loudly opposed — and they didn’t see the need for Amanullah and Queen Soraya to travel and study the innovations of Europe.

By the time the king, who’d never before left his land, returned after seven months overseas, the mullahs looked at him as an agent of Satan.

The 1928 European sojourn of the Afghan monarchs that began in Italy and ended in Turkey seven months later was so extraordinary that every state banquet, every parade, every day in the itinerary warranted front-page coverage in the New York Times, the Times of London, even Isvestia in Moscow. In fact, the welcome given to King Amanullah from European VIPs was so over-the-top that other world leaders became furious; the U.S. press huffily noted that never had any American president traveling anywhere rated such hoopla and fanfare.

King Amanullah and Queen Soraya — after crossing over the mountains that effectively divided their country from the twentieth century, traveled to India, where the king rode his first steamer ship, this one to Egypt. And he and the queen immediately caused a stir: Amanullah for wearing a top hat in a mosque and the queen for taking off her veil — in a devoutly Muslim country.

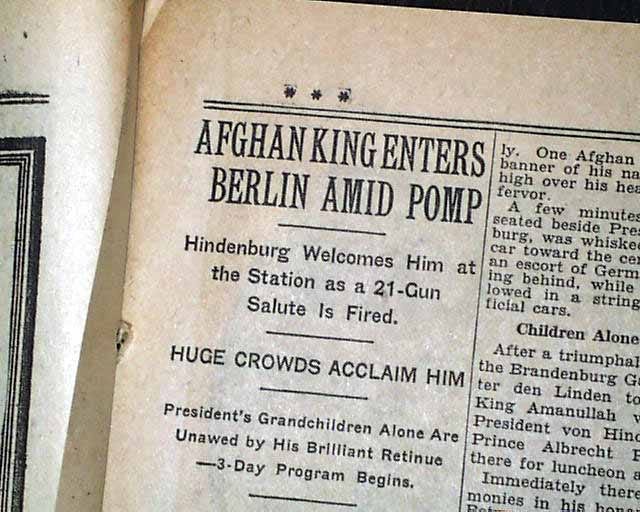

From Egypt they traveled to Rome — meeting the Italian king, the pope, and Prime Minister Mussolini. They toured France’s wine country with the French president, and they were welcomed in Germany by a screaming mob of fifty thousand, a 21-gun salute, and the hovering airship, The Hindenburg, which was renamed The Duke of Afghanistan that day.

The German president was so thrilled to meet the monarchs that he gave them a plane.

When Europe’s leaders looked at the Afghan king they saw telegraphs and telephones, railroads and dams, lighted streets and stores brimming with European goods; they saw a leader in need of shiny, new arms.

The Afghan royals were feted by King George and Queen Mary at state dinners in England, where they lodged at Buckingham Palace, with a side trip to Oxford University, which presented Amanullah with an honorary Ph.D.

British officers wheeled out their latest toys — taking them for rides on submarines, on bombers, and on warships, and rolling out tanks to show how easily a house a mile away could be reduced to flaming dust. King Amanullah, a fierce warrior himself, was visibly shaken by the demonstration, calling Western war “unromantic and terrifying” and noting that he’d never before been so amazed or so frightened by arms.

The British parliament gave women the right to vote during their 1928 stay; Queen Soraya’s exposure to that idea was sure to have a backlash once the couple got home, opined the New York Times, noting that the veil the queen was forced to don in Afghanistan had entirely disappeared during the European trip.

In Russia, wherever they appeared — state banquets or horse races — the band played the Afghan national anthem over and over, and they were continually rushed by screaming mobs. When their steamer ship left for Turkey, Soviet warplanes pummeled the vessel with hundreds of decorative “bombs” that exploded flowers.

The grand salutations and five-hour-long feasts, the dazzling military displays, the operas, and the endless parades weren’t simply shows of European-style hospitality; the acts were laden with expectation, the gifts tied with sticky strings.

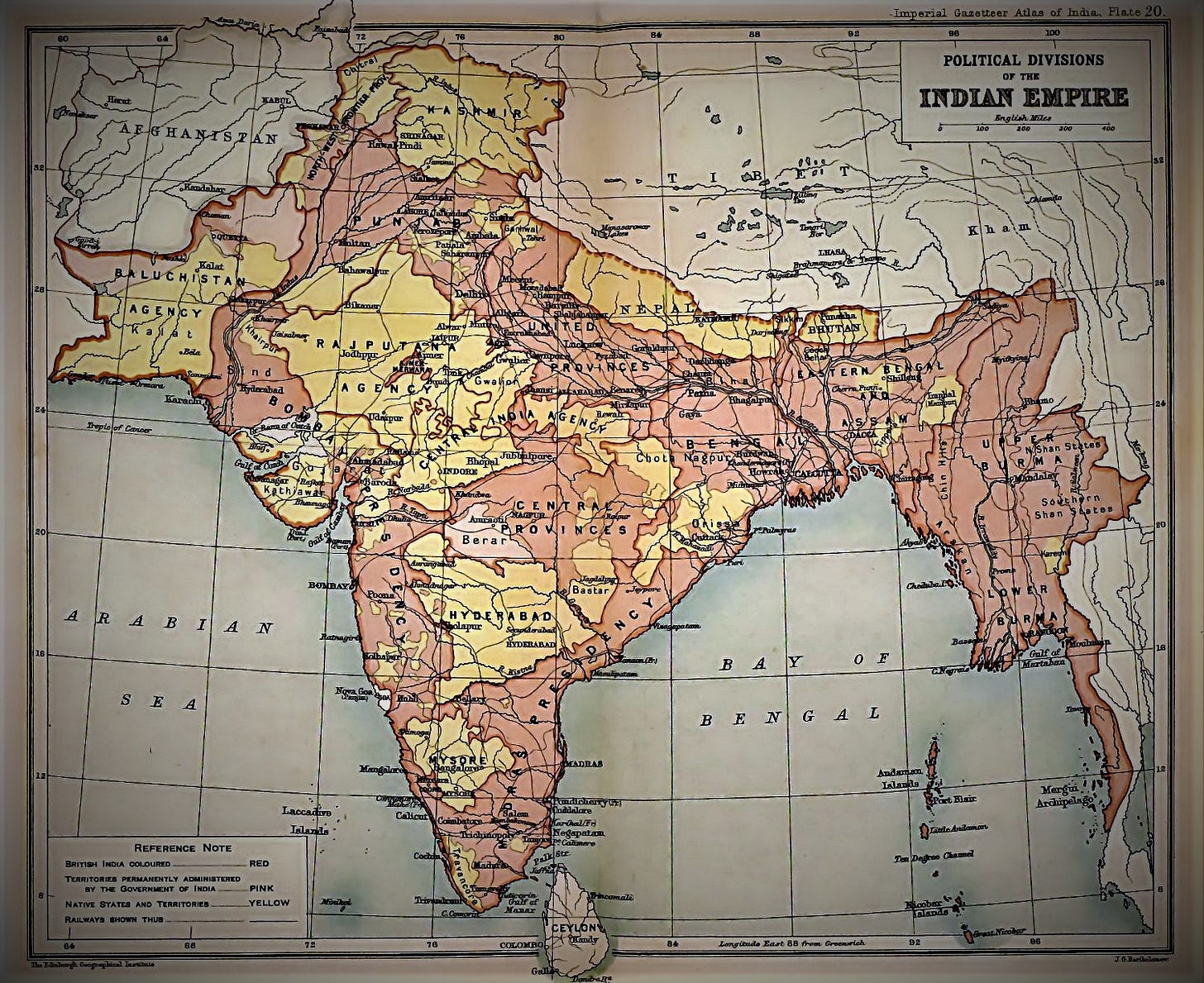

For one thing, Afghanistan lay at a crossroads of central Asia — just south of the Soviet Union and just west of British India, Great Britain’s most important colonial holding.

Both Russia and Britain maneuvered to control this strategic chunk of land, as they had for centuries in what was known as “The Great Game.”

But now other countries wanted in, too: being rail-free and largely road-free, Afghanistan was a geographical trade barrier to the East. Besides, Western Europeans were on a development kick and angling to build up Afghanistan — a surefire means to replenish the coffers depleted by World War One.

Afghanistan, where electricity had barely arrived, most lived in mud shacks, and an outdoor latrine served as bathroom for those who weren’t royalty, appeared to Europeans to be a perfect place to put their engineering know-how to use.

The royal trip, in fact, was a research mission: King Amanullah was investigating rail lines, factories, and armament plants, figuring out how best to modernize his land, and to whom he should hand out development contracts. He hoped “to plant all of the good things of European civilization in my country," he announced in Berlin.

And European leaders were ready to help. When they looked at the Afghan king they saw telegraphs and telephones, railroads and dams, lighted streets and stores brimming with European goods; they saw a leader in need of shiny, new arms.

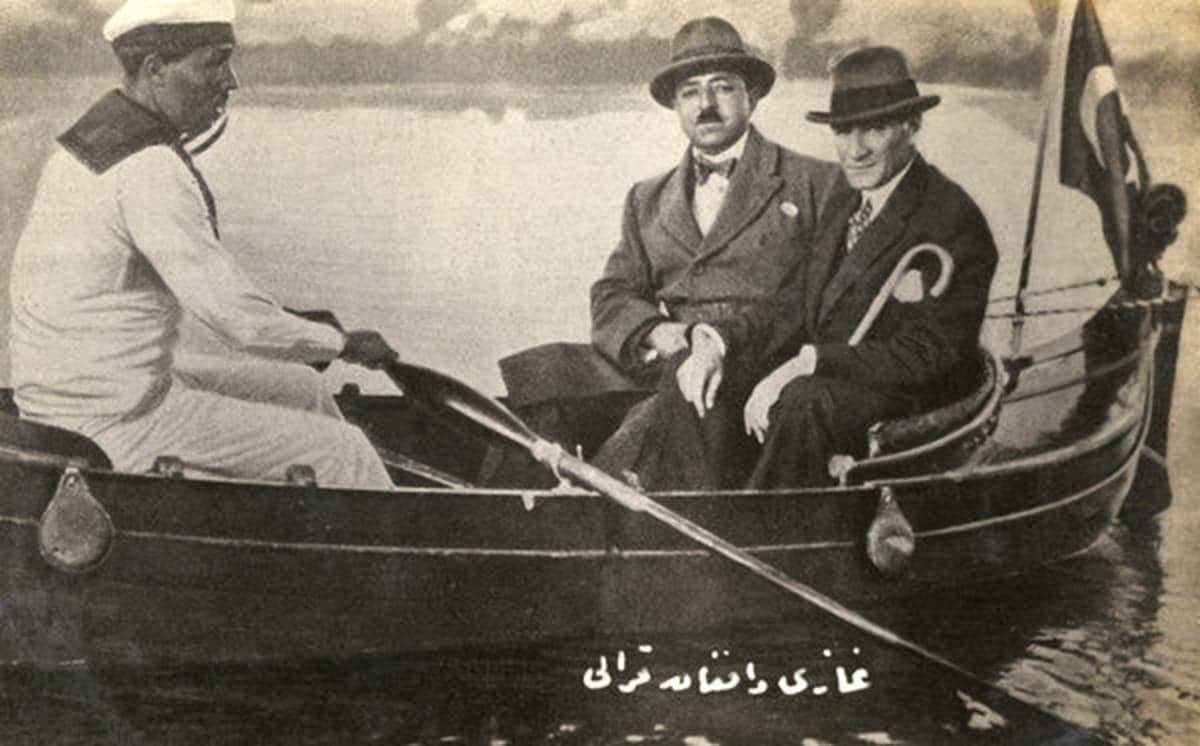

While most continental VIPs salivated to snatch up the king’s business, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the president of Turkey, presented himself as a friend and mentor, being the leader King Amanullah most admired. In Ankara, where the two leaders signed a friendship treaty, Amanullah told reporters that in Turkey he felt that he was among brothers. “The Turkish nation is one eye and Afghanistan is the other,” he explained.

In Istanbul, the Afghan monarchs lodged in the lavish Topkapi Palace, previously home of the ruling Ottoman sultan, and were taken to the palace’s inner sanctum holding relics of the prophet Mohammed: his sword, his grail, even a hair from his beard, treasures that certainly held sway over King Amanullah, leader of an Islamic land.

Of all the monarchs who had wined and dined Amanullah, nobody influenced him as much as Atatürk. The Afghan king was awed and inspired by the Turkish leader’s success in westernizing his country, the shrunken, post-WWI remains of the once-expansive Ottoman Empire.

In bringing Turkey up to speed, not only had Atatürk separated the Islamic religion from government, he’d even ordered that Turks, who’d been writing in Arabic script for 1000 years, instead adopt the Roman alphabet used for writing English.

Atatürk’s cultural transformation was greatly bolstered by his ordered changes in the Turkish dress code: he banned the fez for men and forced Turkish women to unveil.

And he urged the Afghan king to make exactly such a symbolic demand of his people — to take off their turbans and shed their veils.

Fashion is power, Atatürk taught. Control the clothes, control the people. Unfortunately, upon his return to Afghanistan, King Amanullah heeded his advice. And that’s when the situation turned truly bizarre…