Panama, A Presidential Obsession

A defining issue for three previous presidents, the Panama Canal is again headline news. A volcano, a Frenchman, and blood-sucking warriors have everything to do with its creation by the US.

This is the second installment of “A Country, A Colony, and A Canal,” which looks at three locales recently mentioned by President Donald Trump.

(The first installment — Greenland — can be found here.)

During his first official press conference of 2025, incoming president Donald J. Trump signaled his desire to expand America’s geographical size bigly. He pointed at sprawling Canada — the world’s second-largest country, which he covets as the 51st state — and he pointed at Greenland, a massive, mineral-rich island holding more territory than Texas, California, Montana, New Mexico, and Arizona combined.

But then he pointed at an itsy-bitsy li’l squiggle that barely shows up on the world map.

In that third case, however, size didn’t matter, since he was referring to that strategic chokepoint called the Panama Canal, which connects the Pacific and Atlantic — and is crucial for maritime trade, especially to and from the US.

Most goods traded between Asia and the East Coast of the US pass through the canal as does cargo going between Europe and the West Coast. Panama is also a major transit point for cocaine heading to Europe and beyond.

Celebrating its 110th birthday last August, “The Big Ditch” is a stupefying engineering marvel involving six pairs of locks, two dams, two artificial lakes, and a hydroelectric plant. Crossing the canal takes around ten hours from start to finish — and transit fees are steep: container ships typically pay from $60,000 to more than $300,000 depending on weight, size, and cargo.

But the Panama Canal is way, way more than a vital waterway between two continents that connects the world’s two largest oceans.

The Panama Canal is a symbol, a potent one, that represents so many things at once.

It’s a symbol of American ingenuity and of a painful French failure. It’s all wrapped up with Panamanian independence — since support of the country hinged on the US building a canal there. It’s an emblem of foreign intervention and of humans ultimately vanquishing nature after centuries of deadly struggles.

And it’s a reminder of how a volcano can alter the course of the world.

The creation of the Panama Canal and the birth of that country — and they are very much connected — had everything to do with a volcano 1400 miles away that blew its stack at a pivotal moment, a tale we’ll be getting to shortly.

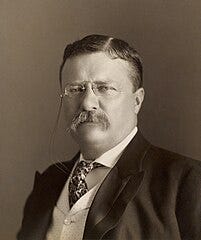

Wrapped up with a stamp, a flag, and a drug-running CIA asset turned dictator, the Panama Canal is such an emotion-packed icon that it’s been an obsession of three previous presidents — Teddy Roosevelt (who committed dubious acts to get it made), Jimmy Carter (who considered his 1977 Panama Canal Treaties his most important act in office), and Ronald Reagan (who snatched the presidency from Carter in 1980 after making the canal his signature issue.)

In 1977, Carter negotiated the Torrijos-Carter treaties, controversially ceding control of the canal to Panama, effective 1999. Reagan’s stance was “We built it. We paid for it. It’s ours.” Trump appears to be echoing that popular line.

And for Trump, too, it’s a symbol — of ingratitude and Beijing.

Trump recently alleged that the canal, which has been run solely by Panama since 1999, is “being operated by China – China! And we gave the Panama Canal to Panama, we didn’t give it to China,” Trump said. “And they’ve abused it, they’ve abused that gift.”

Panama’s president says that Panama alone controls the canal, which appears to be the case.

However, China does indeed have its fingers in many Panamanian pies.

China is now Panama’s biggest trade partner, for starters, and a Hong Kong (i.e. Chinese) outfit, CK Hutchison Holdings, leases two ports along the canal — on its Atlantic and Pacific sides — seen by some as threats to US security, particularly if war erupted with China. A Chinese consortium is also building a $1.4 billion bridge over the passageway among numerous other Chinese projects in Panama and across Latin America that the US press often ignores.

It’s unclear if Trump simply wants reduced tolls — which he’s called “exorbitant” — for US vessels crossing the canal or if he plans as well to demand that Panama disentangle itself from the many Chinese investments there. Trump’s incoming “border tsar” has further stated that the administration wants to close off the Darién Gap, the danger-filled jungle bordering Panama through which 300,000 migrants, mostly Venezuelans, traveled last year to the country en route to the US.

A Geographic Standout from the Start

Since about the second it was first spotted, the crooked finger of land known as the Panamanian Isthmus has grabbed attention thanks to its strategic location.

Once Europeans moved in starting with Vasco Núnez de Balboa in 1501, the then-mostly undeveloped territory quickly became a major transportation route.

For more than 300 years, the Spanish and their slaves crossed the land via the rugged Camino Real — the Royal Road — hauling gold, silver, and everything else across mountains, swamps, and jungles, to get from the Pacific side to the Atlantic, or, more specifically, to the Caribbean Sea as the Atlantic is known here, where the goods were loaded onto European-bound ships.

In 1821, residents of the Panamanian isthmus declared independence from Spain; for protection, they forged with other territories, known at points as New Grenada and Gran Colombia — with the isthmus ultimately becoming a province of the Republic of Colombia.

Panama was Colombia’s golden territory — because everybody who glimpsed it began wracking their brains on how to make it navigable.

And starting in 1848, its enticements gleamed even more brightly — when gold was uncovered in California, kicking off a migration to the West.

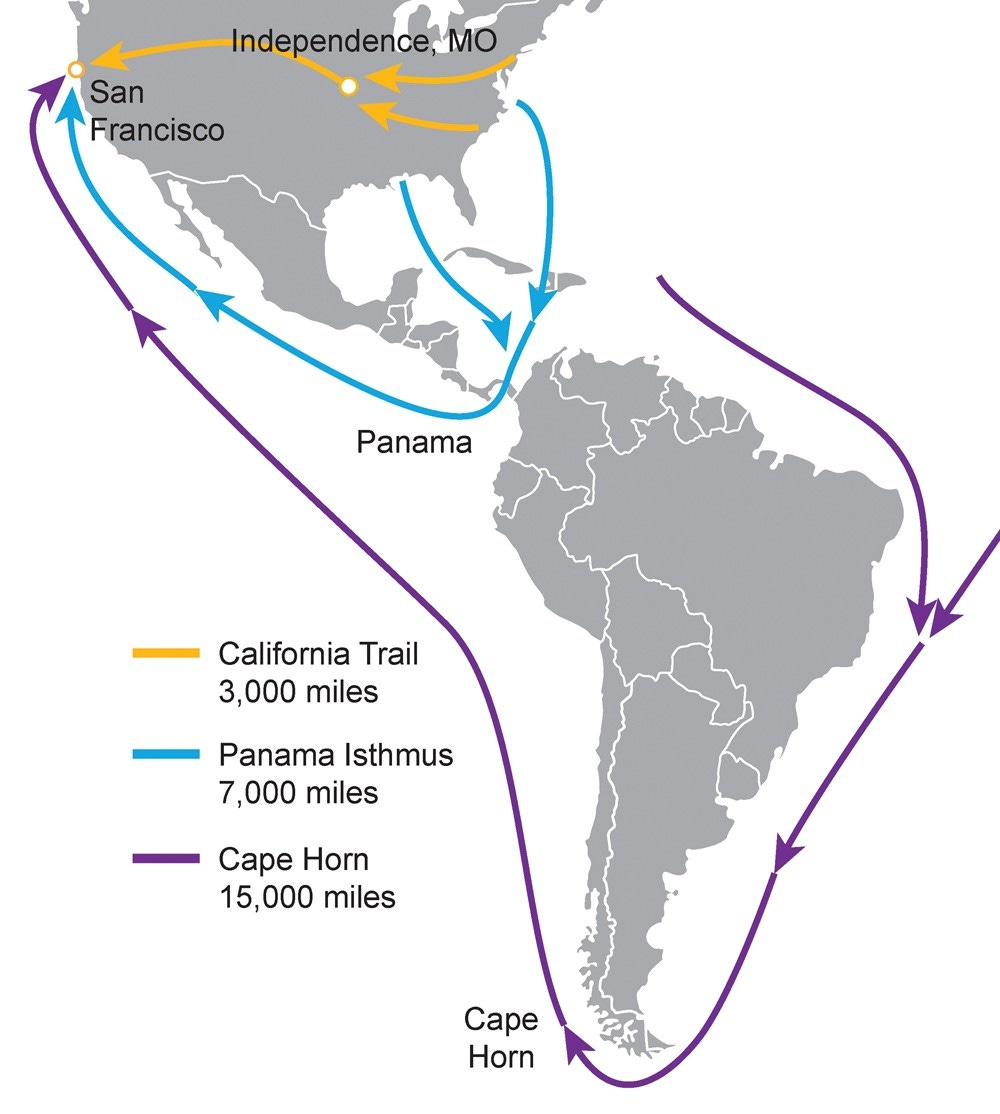

Getting there via the “California Trail” was arduous and danger-filled, as transcontinental railroads did not yet cross North American— they wouldn’t be running until 1869. Most of the 150,000 who ventured out over the land did so in oxen-drawn wagon trains that crossed mountains, rivers, and vast plains, where indigenous tribes lived and buffalo still roamed.

The overland route adventure took half a year. And it also took six months, maybe nine, to travel by steamboat from New York around the cape of South America to California.

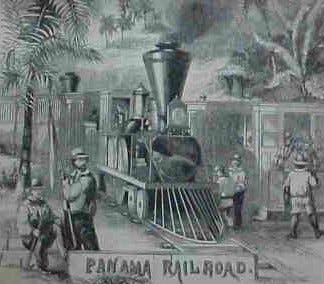

Around then, a US company backed by New York financiers shored up on the Panamanian Isthmus. Negotiating rights with the Colombian government, the New York company undertook the immense project of building the Panama Railroad across the isthmus to move people and goods that arrived (via steamboat) on the Atlantic side of Panama across the rugged terrain to the Pacific side, where passengers caught ships to California.

The 1846 Bidlack treaty also gave the US the right to protect the train in the face of violence.

Opened in 1855, the Panama Railroad quickly became the most profitable in the world, although as many as 12,000 or more workers died from malaria and yellow fever while building it.

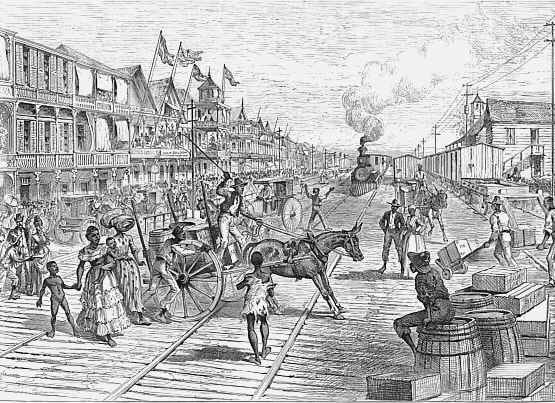

As California-bound 49ers piled in waiting for ships, they brought the “Wild West” to Panama — general unruliness, fights, even riots, often broke out.

With the Gold Rush came even more interest in building a canal along roughly the same route as the Panama Railroad.

President Ulysses Grant broached the need for a canal in his first presidential address to Congress in 1869 — sending seven survey teams to the isthmus, before ultimately deciding a canal there just wasn’t feasible.

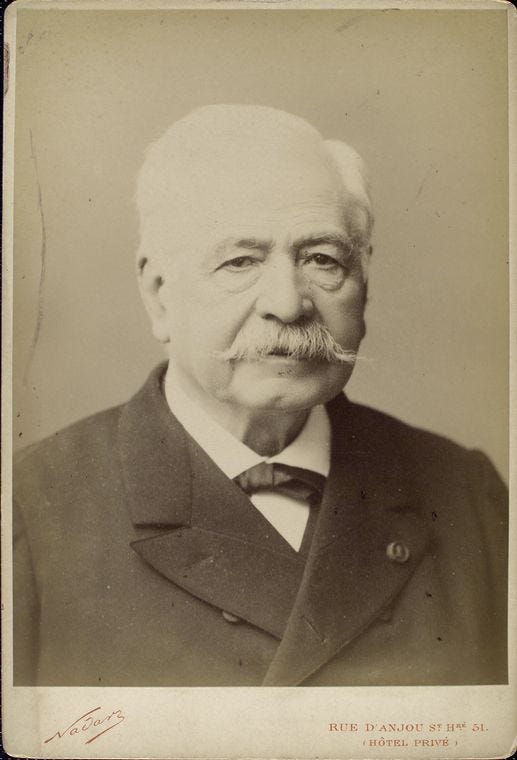

Ferdinand de Lesseps, however, had other ideas. The Frenchman, having overseen the building of the amazing Suez Canal, which was completed in 1869, now formed a new company to build another miracle — this one in Panama. A diplomat, but clearly not an engineer, de Lesseps insisted that, just like the Suez, this new artificial waterway would be a sea-level canal, built without locks.

Never mind the spine of mountains they’d have to cut through, never mind the jungles and swamps, never mind the snaking “monstrous” Chagres River that violently flooded every rainy season and crossed the route 14 times.

And never mind the diseases, like malaria and yellow fever, that plagued those who stepped foot on the isthmus. Despite the rigors and challenges, the French would be victorious in this Mission: Impossible, de Lesseps insisted. And he kept on assuring the public that the sea-level canal would succeed year, after year, even though that wasn’t how it appeared on the isthmus.

Meanwhile in Panama…

Thousands of workers died from malaria and yellow fever right off the bat. The construction firm, realizing that a sea-level canal without locks was sheer folly, pulled out. The river kept flooding into the huge ditch the French were digging — causing mudslides and forcing workers to re-dig what had already been dug. Estimates for how long it would take to finish the canal stretched to eight years, maybe 12. Costs skyrocketed; corruption abounded. Workers kept falling ill. Corpses were piling up of those killed by malaria and yellow fever.

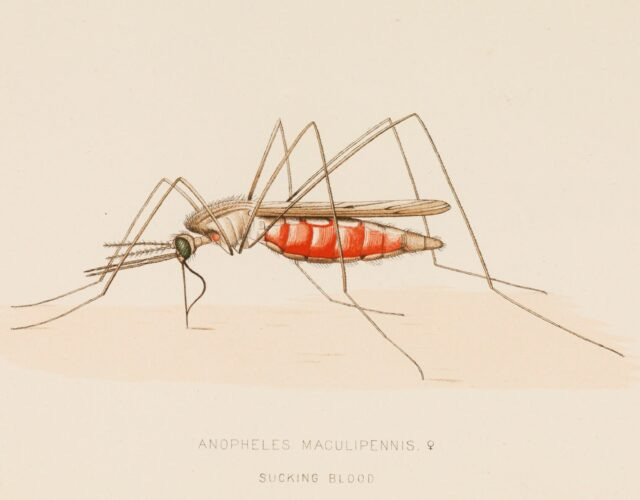

It wasn’t until the early 1900s that medical researchers realized that mosquitoes were the vehicles transmitting malaria and yellow fever, which previously were believed to be caused by bad earth and foul air.

But no problem, said de Lesseps, who wasn’t there.

Except for two short visits, he stayed in France with his young second wife and their twelve children — sending his eldest son, Charles, to oversee the mega-project.

Without informing investors of the many woes, the elder de Lesseps sought out more financing to contend with the challenges. French newspapers kept cheering him on and painting the project rosily; French officials and parliamentarians approved his bond sales and “lotteries” that raised many millions more for the canal cause.

When the French minister of public works, Charles Baïhaut, realized how miserably the company was actually doing, he blackmailed de Lesseps not to reveal it, demanding he pay some $50,000, according to the chief engineer of the project.

But despite the charade, by 1889, the truth came out and the canal company went bankrupt. Over 22,000 workers had died — for naught, it appeared. Charges of corruption and bribery soon emerged — with assertions that de Lesseps and his son had paid legislators to allow more lotteries and bribed newspapers to give glowing reports and mislead investors.

Some of those involved in “The Panama Affair,” committed suicide or fled France; both Lesseps and his son were found guilty and fined, though the latter’s prison sentence was suspended. The elder de Lesseps, his brilliance now tainted, descended into silence, dying in 1894, age 89, when his youngest child was 4.

Only the minister of public works, Charles Baïhaut, served time — three years of his five-year sentence.

It was a blow to the French spirit. Nearly $400 million had been squandered, and 800,000 French citizens lost their investments.

Beyond his insistence that the canal be made without locks, de Lesseps didn’t take into full account the region’s fierce warriors. known as Anophelines and Culicines. Which is to say mosquitoes, symbols of doom — especially to the French.

Two French Failures That Helped the US

Every country has its problems with disease-carrying pests, but the French experience with the world’s deadliest animal, the mosquito, led to two of the biggest embarrassments ever in that country’s history — both of which greatly benefited the United States.

In 1802, Napoleon’s French forces amassed on the Caribbean island of Santo Domingo, today’s Haiti, planning to move on New Orleans, wrest control of the Mississippi, and extend the French empire into land west of the river. But plans went seriously awry because of the deadly ankle biters, which carried yellow fever and permanently felled thousands of his troops, forcing Napoleon to abandon the plan.

That failure prompted Napoleon to instead sell the land west of the Mississippi to the US in 1803, in the Louisiana Purchase that doubled the fledgling country’s size.

And mosquitoes were largely responsible for the second French washout in the region: de Lesseps attempt to build the Panama Canal. Halted due to worker deaths, a ridiculous design, and bankruptcy, it ultimately was taken over by the United States.

It should be noted that in both cases, some Frenchmen made money on the deals.

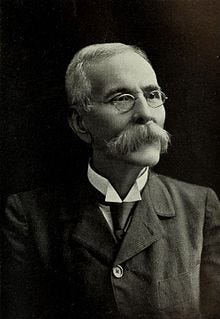

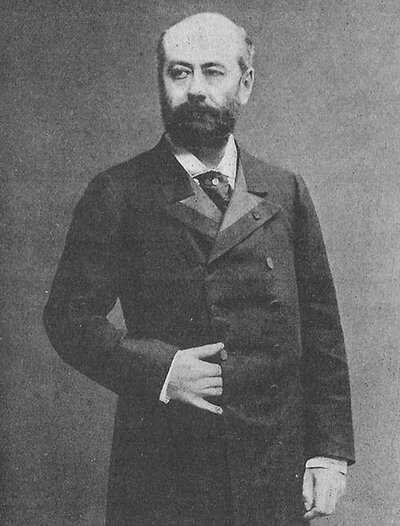

Despite the humiliation of the halted canal, one man thought the project could still fly — at least if locks were added the design. And he knew the project well, being the former chief engineer: Philippe Bunau-Varilla.

Hired by de Lesseps to work on the canal fresh out of engineering school in 1884, Bunau-Varilla had quickly ascended to the top post, simply because unlike so many of his colleagues he hadn’t quickly died. He tried to talk sense into the old man, insisting the canal needed locks and a dammed river. But by the time de Lesseps listened to him, the company was belly up.

“The Man Who Created Panama”

When French liquidators moved in to sell off whatever canal assets could be sold, forming a new company — Compagnie Nouvelle — Bunau-Varilla saw his opportunity and swooped in, becoming the majority stockholder.

And then the Frenchman set out to resurrect the Panama Canal, hoping to sell off the whole kit-and-kaboodle for a mere $109 million — that included machinery, housing, land already dug and the still-valid rights to the land.

The engineer-turned-salesman traveled to Russia, where Tsar Alexander II took a deep interest — and the project looked like it might yet fly — until the tsar was promptly assassinated in 1888. Bunau-Varilla hit up the British, but they were consumed by the Boer War in South Africa.

So in early 1901, he sailed to New York and began lobbying across the United States — giving lectures and bending the ears of anyone and everyone in power, and getting through to quite a few. He was an influential speaker and a social charmer as he worked his way into well-heeled and political circles.

The Spanish-American War Makes Case for a Canal

In the US, interest in building a canal had recently been revived. During the Spanish-American War of 1898, the warship Oregon, docked in San Francisco, was called for battle in Cuba. Since it had to go around the cape of South America to get there, the Oregon didn’t show up for nearly ten weeks.

President William McKinley appointed a commission to look into where to build a canal. However, his assassination in September 1901 catapulted Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, 42, and the youngest president ever, to the top seat. And Roosevelt was gung-ho on naval power — and a canal.

By late 1901, when Frenchman Bunau-Varilla showed up, it was clear that the United States most definitely wanted to build a canal – it was the talk of the White House and Congress and headline news in the burgeoning press.

However, the US was going to build the canal in Nicaragua — 700 miles northwest of Panama.

Nicaragua wasn’t as developed as Panama, but it appeared more politically stable than the isthmus where rebels had made several attempts to secede from Colombia. And Nicaragua didn’t have the taint of disease or the stench of French failure that still hovered in Panama. Some articles painted Nicaragua as a disease-free utopia, with regions so salubrious, they said, that nobody died.

However, a few, engineers among them, believed Panama was the more viable option. After all, the French had excavated extensively, their machinery was still on the site (and maintained), their buildings still stood. Not to mention that they held the still-valid concession granted by Colombia to dig the canal.

As Bunau-Varilla kept pointing out, the Panama route would be shorter and straighter than in Nicaragua. A canal in Panama would require fewer locks, the isthmus had better harbors, and it would cost less than starting anew in Nicaragua. But the point that Bunau-Varilla kept hammering home — so much that friends implored him to stop as they didn’t think it relevant — was that Nicaragua has 13 volcanoes. Panama was volcano-free.

Nicaragua remained the top pick by Congress, by the people, by the press — all the more when the Canal Commission released its report, saying Nicaragua was the way to go.

Bunau-Varilla was about to pack it up and slink off with his “pick up the broken pieces” canal package for $109 million, when he received a surprising query through the DC grapevine. Would he drop the price to $40 million? If so, the US might indeed be interested.

So the price tag was slashed and the Frenchman stayed in the US and carried on with his fight.

Roosevelt now favored Panama, but legislators, influenced by the commission’s report, still wanted Nicaragua. Roosevelt called in the commission’s members and ordered them to publish a supplemental report — and unanimously support Panama, which they did.

Legislators weren’t buying it, though. To help dissuade them from Nicaragua, which they were sticking with, Bunau-Varilla sent them a pamphlet he’d written illustrating why Panama was superior from an engineering point of view.

It didn’t move the needle.

But that spring when US senators were closing in on a final vote, the Caribbean Island of Martinique changed the course of the world when Mount Pelée spectacularly erupted — killing 30,000 onlookers in minutes.

Causing mudslides and three tsunamis in the days before, Pelée loudly exploded on May 8th and belched a huge and horrifying black cloud of searing ash that darkened the skies for 50 miles and blanketed the island town of St. Pierre — killing almost everyone, leaving only a handful of survivors. The world was stunned.

A few days later, a volcano on St. Vincent rumbled. Then, Mount Momotombo in Nicaragua erupted as well, though not so dramatically.

Seizing on the terror of the moment, Bunau-Varilla headed to collectors’ shops and bought up 90 Nicaraguan 1 centavo postage stamps — which showed Mount Momotombo emitting a plume of smoke. He sent a stamp to every senator, with a note: “An official witness of the volcanic activity on the isthmus of Nicaragua.”

This ploy worked.

For the last count, eight more senators voted for Panama than for Nicaragua. Uncle Sam wrote out a check for $40 million to the French Compagnie Nouvelle, the biggest government expenditure at the time.

A treaty was quickly negotiated between the US and Colombia — that gave the US a 100-year renewable lease and control of the canal and a six-mile strip alongside it in exchange for $10 million and an annual payment of $250,000.

Still More Hoops to Jump Through

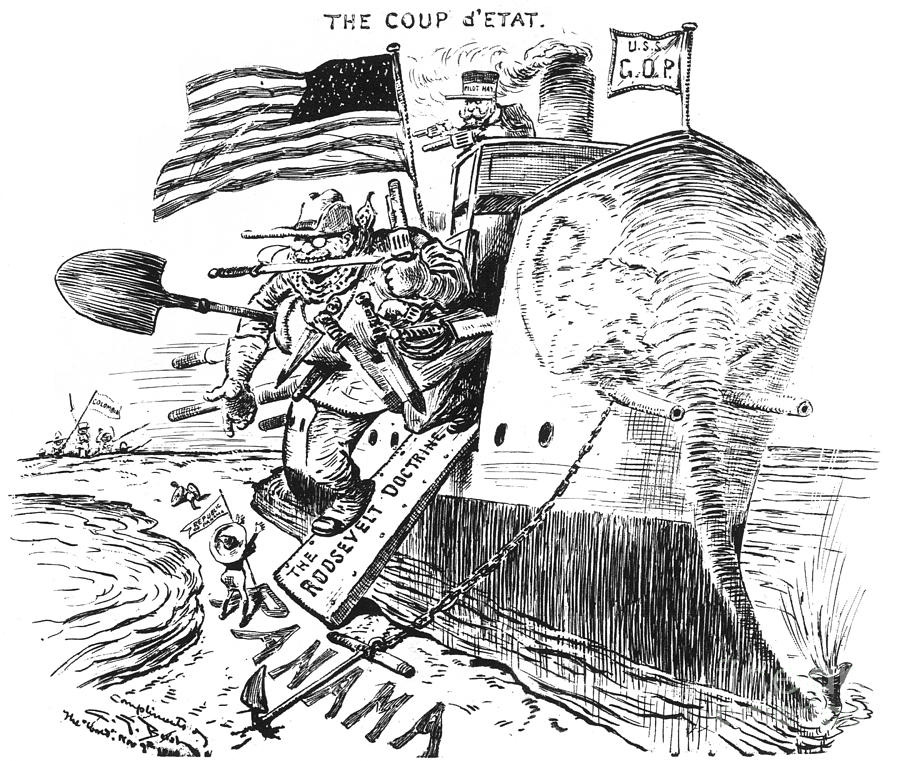

Quickly ratified by the US Senate, the treaty was rejected by the Colombian Senate. Roosevelt was livid and refused to renegotiate it.

Besides, Bunau-Varilla had a new trick up his sleeve.

Having worked in Panama, he was well acquainted with wealthy landowners on the isthmus, and he knew they were ticked that the Colombian senate had nixed the treaty. Talk was beginning anew about seceding from Colombia. Secessionists had even come to the US recently looking for support and funding. At one point, the rebels thought they had both, but they were ultimately rebuffed.

In October, the Frenchman summoned Manual Amador a 70-year-old physician and one of the leaders of the potential secession movement, to DC. Bunau-Varilla offered to pay the rebels $100,000 of his own money, if they broke off from Colombia very soon and agreed to a treaty with the US for a canal in their new country of Panama.

Nothing if not prepared, Bunau-Varilla formulated and put together the whole secession package. He devised a battle plan for securing the isthmus, he wrote a constitution for the new country (based on Cuba’s), he penned Panama’s proclamation of independence from Colombia — he even supplied Amador with a silk flag that Bunau-Varilla designed.

And though nothing was ever committed to paper, he extracted a commitment from the Roosevelt administration to send gunboats to Panama to protect it from a Colombian incursion when the rebels seceded.

The thinking was that the 1846 treaty gave the US the right to intervene.

The only catch, beyond acting very quickly and giving a nod to the canal, was that the leaders of the new Panama had to agree to name Bunau-Varilla as Panama’s Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States, thus giving him the powers to negotiate a treaty for the canal.

With US warships watching on from both the Pacific and Atlantic sides of the island and blocking troops from Colombia from arriving, the rebels seceded bloodlessly — using some of Bunau-Varilla’s money to buy off Colombian generals and troops already on the isthmus.

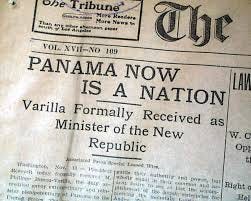

On November 3, 1903, the rebels proclaimed the formation of the country of Panama with Amador as their president — and reluctantly named Bunau-Varilla as their minister. Fifteen days later, a new canal treaty — between the US and the new country of Panama — was signed.

In negotiating the treaty, Bunau-Varilla gave the US even more rights than the earlier one rejected by Colombia. As put forth in Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty of 1903, in exchange for a one-time payment of $10 million, and $250,000 to be paid each year thereafter, Panama gave the US the right to control the canal and 10-mile-wide canal zone as if it were sovereign — in perpetuity.

Panamanians weren’t thrilled with the terms, but Bunau-Varilla pushed their new Senate to quickly ratify it, saying the US would pull back its naval support if they didn’t. The treaty was ratified in two weeks in Panama and in the following February in the US.

And having completed his task, Bunau-Varilla stepped down as Panama’s minister, and sailed back to France.

But, as we will see in the following post, the Panama show was just beginning…