I'd been searching for it for years. A certain jacket. A sleek, form-fitting, black jacket, something with white trim. After nearly a decade, I finally found the jacket in Seattle and brought it to Paris.

I'd never been to France, but having found myself the proud owner of an unexpected credit card, I was off to Europe to write about nightlife on the continent.

I wore the jacket my first day in Paris and was immediately disappointed.

Montmartre, the city’s hilltop hamlet crowned by the gleaming white dome of Sacre Couer, had apparently been the wrong choice.

Except for the neon-lit, windmill dance hall Moulin Rouge, the steeply-inclined village appeared shuttered-down and dead on that sleepy Sunday.

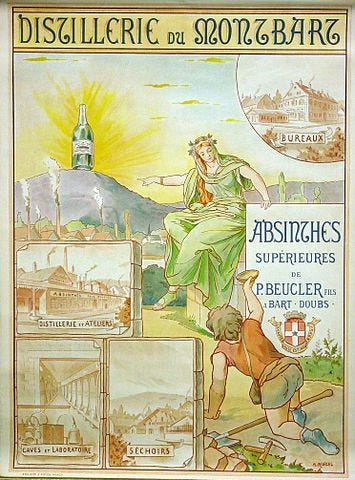

I wandered up winding Rue Lepic, past the stately Haussmann-era white apartments with mansard roofs and wrought-iron balconies, then snaked down back streets, imagining an era when Cancan girls danced from the bar, and Toulouse-Lautrec and Manet sat in cafes stirring sugar into emerald absinthe, once so commonly drunk that early evening was called "The Green Hour."

Absinthe was no more, having been outlawed a century before, and the skirt-lifting Cancan girls had long ago hopped down off their bars; that night when Montmartre was snoring, I was doubtful there'd been a scene since.

Until, there on a corner, a few blocks up from Moulin Rouge, I spied it.

Caf' Conc'.

Specifically, I saw two outside tables on the sloped sidewalk. And at one of them sat a group of devastatingly handsome French men alongside several Parisian beauties. So I sat down beside them and ordered the three-course prix fixe, happy to be wearing my jacket, which I imagined made me look très chic in a very French way.

The Parisians didn't seem to notice either me or my jacket, so I plunged into my food.

First, a composed salad with small potatoes and green beans drizzled with champagne vinaigrette. Then herbed chicken in a cognac-spiked mushroom sauce. For dessert, a wedge of creamy Camembert. And the entire meal was washed down with a fruity red wine poured from a ceramic pitcher, its painted flowers now faded. This small feast that had me in the throes of ecstasy cost about $12.

Next to me, the gorgeous French people were yukking it up, talking away to themselves. Not one stray word was thrown my way after two hours, not one faint Mona Lisa smile or curious glance tossed my direction, not a hint that they even noticed my jacket, even though I was sitting a mere half-a-baguette away.

I burrowed into The Creators, cursing myself for having studied Russian, not French.

The sound of "La Bamba" drifted out to the sidewalk. The waitress, using sign language, urged me to go inside and check out "le disco." Sated, happy, and suddenly shy, I instead ambled down to my hotel, after asking the cheery waitress her name (Linda) and sending my compliments to the chef (Gerard).

The Hamlet Snaps To

The next night, after a day spent walking through a small cemetery thick with moss, and lunching at one of those ubiquitous wicker-chaired cafés, I again strolled up Rue Lepic, searching for someplace to eat.

That night Montmartre was awake, the many restaurants hopping, white-jacketed help bustling about. Not far from the square of water-coloring artists, I peeked into copper-laden brasseries decorated with gleaming pans, then into luxe restaurants with white linen and fresh flowers, even a Mexican joint where they served bread chunks for chips and a lone taco rang up at $15.

Still intrigued by the scene at Caf' Conc', I returned to the spot where nary a tourist (except me) wandered through. When a warm rain swept across the serpentine street, I ventured inside to find the same crowd as before, plus about twenty more.

In the closet-sized front room, an Edith Piaf song crackled from the small plastic radio on the curved metal bar that comfortably fit three alongside an ice bucket just large enough for five cubes. Ice, carefully tonged from the bucket, seemed a precious commodity, lending a feeling that I'd stepped into another time.

Beyond, the dining area was divided into two parts. One step up was a small chamber, tinier than a boudoir, its stone walls cluttered with ticky tack: yellowed prints of bridges, tattered 50’s postcards, and watercolors of Sacre Couer hanging crookedly. Three gouged-up wood tables for two filled the cramped space; the rickety chairs didn't match, nor did the silverware, plates, or odd-sized wine glasses tinted a rainbow of shades. The whole eatery seemed to have been furnished by a mad dash through a flea market.

Up a few steps, another group of Parisians gathered around a long glass table with a vase of burnt orange gladiolas in its center, laughing and gesturing in that flamboyant French way that made me think they were close kin of the Italians.

I sat at a table for two and ordered the prix fixe. This time the main course was a perfectly-puffed omelette folded over butter-drenched asparagus and smothered with cheese. And the salad had white corn in it. And this time the locals were noticing my presence, though no one except Linda actually talked to me. I presumed because they didn't speak English.

A New, Cool World Opens Up

On my third night there, while I was taking my first bite of fish in a sauce of white wine and capers, a raucous folk song came over the radio; everyone swung their arms around each other and joined in singing. Having come from stoic Seattle, where denizens wore glazed looks of ennui, the sight of these Parisian hipsters hamming it up and singing along to an accordion tune was startling. I nearly felt embarrassed for them, until I recalled this was France and people were allowed to be festive.

I was even more shocked when a dashing young man with gray eyes and curly, raven-black hair pulled me away from my meal and led me out to the sidewalk to dance.

All I could think as he twirled me around was, "This is why I came to Europe. They have a different kind of fun."

After the sidewalk dance, Jean-Paul and his friend, a handsome actor, sat down at my table, and several more of the regulars pulled up chairs, with everyone stopping by to officially meet me. Even the cook Gerard, a gruff, heavily-tattooed ex-merchant marine, emerged from the kitchen with a broad, yellow-toothed smile and kissed my hand.

And that night I discovered most of these French people spoke my language, the most heart-stoppingly lovely English I've ever heard. In their melodic, sensually accented take on the Queen's version, they complimented my black jacket. They asked about the book I’d been engrossed in the previous two nights. And they insisted I accompany them downstairs to le disco.

Le disco was a très dank stone cellar with a half dozen tables encircling a dance floor not much larger than a parking space; along the back wall, about three centimeters up, was a tiny stage where Paco the DJ, wearing sunglasses, played European bands I'd never heard of, like Mano y Negra, who sounded like Dire Straits with a Spanish accent and a French flair.

Unlike Seattle, everybody was dancing, and everybody was laughing as they swirled into the morning doing the Parisian take on swing. And I kept thinking, This is it, my God, I've finally found it: the scene I've sought my entire life, where the regulars are lovely, the conversations lively, the food divine, the drink good and cheap, the setting quite cozy, the music wondrous and everyone dances and laughs. My definition of nirvana.

I didn't realize then that, there at Caf' Conc,' I'd stumbled upon the “Three-Day Formula”: if you hang out for three consecutive days in the same place you can often make your way into the local scene. Nor did I know that I'd put this party crashing technique to use all across the globe, and that sometimes the “Three-Day Formula” would take only two.

But I knew the door was open and that my prejudices about snooty Parisians were melting away.

By the end of the week, I was on first-name basis with one and all: Rosan and Daniella, the gorgeous Moulin Rouge dancers; the owner Robert, a middle-aged man with dancing eyes and receding gray hair who, as a former music manager, had booked Europe’s top acts; Kenny, the British jazz musician, who spoke deplorable French, wore baggy plaid pants and continually thanked me for Americans entering World War II, between bumming my smokes.

And Gerard the tattooed cook came out every night and asked, "Très bien, Melissa?" To which I replied every night with the entirety of my French vocabulary: “Oui!"

Even Paco, the reserved DJ, who always wore a snappy navy blue army jacket with gold stripes, deigned to introduce himself. While civil, he was the least welcoming of the bunch, and I sensed a strong anti-American vibe, although it turned out most of these Parisians had distinctly warped ideas about the U.S.

America from the Paris Perspective

Sam, a wealthy, unemployed intellectual, was the most exotic, intense, and opinionated of them all, with ebony hair, sculpted cheekbones, and deep, stormy eyes that pierced you as he spilled out conspiracy theories.

"Why do you think Kurt Cobain died so young?" he demanded one night over a bottle of Cotes du Rhone. "And Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, Jimi Hendrix, and Jim Morrison?"

"Heroin does seen to be a common denominator," I noted.

"No, don't you see?" he asked. "It was the CIA!"

Sam yammered on about the plot to take down all truly talented musicians, shocked that I didn’t already know.

I was enchanted whenever Sam talked, regardless of how preposterous the subject. He could have told me I had broccoli in my teeth and I would have said, "Ah yes, Sam, tell me more!" He made English sound like a language of love.

As for his feeling of love, it seemed to be directed at Rosan. When Sam got up to greet her as she entered, his best friend Henri sat down beside me and took up the slack.

Henri’s Wild Ride in D.C.

With beakish nose, icy blue hawk eyes and a thin fringe of brown hair, Henri looked like Lebeau — the French guy in "Hogan's Heroes" — and he was obsessed by violence in the U.S.

"How can you stay there in America?" Henri asked, quite seriously. "It is amazing you are alive! The guns and the drugs and the killing everywhere!"

Then he launched into a story about his two-day visit to DC, where he'd traveled with a band that he managed. Running late after sightseeing, Henri grabbed a cab, urging the driver to hurry to the club where the band was setting up for that night's show.

"The driver he says to me it is the rush hour, we cannot make it in time — unless he drives through a very bad part of the city. I say drive through the bad part. Then he says to me when he tells me, I must duck down."

Beads of sweat broke out on Henri's forehead.

"So the driver says, 'Duck!' and I duck. At the next street, he tells me, 'Duck!' and I duck. The third time he tells me, 'Duck!" I don't duck, because I think he is making a joke on me. But then there is the gunfire and — BANG, BANG, BANG — the car window next to me is shot out! The rest of the ride when he tells me, ‘Duck!’ I duck...."

Trouble Enters the Tale

That weekend I met a photographer, Philippe, a charismatic rogue with pock-marked skin and a missing bicuspid; nevertheless, there was something alluring about him, partly because he heavily peppered his conversation with “oh la la” or, when warranted, “oh la la la la la!”

Philippe had a shaggy mutt named Gypsy and a friend with a helmet of dark hair. The friend, Denis, was descended from a famous knight, and they both invited me to Denis' inherited 16th-century estate in Normandy.

“And we will drink a Bordeaux that you will adore,” said Philippe. “Ohh la la, it is like silk!”

“To buy it now,” added Denis, “it would cost over 1000 dollars!”

"Robert, they're making it up, aren't they?" I asked.

But the owner confirmed it was true. Philippe and Denis had bought many cases of the wine when it came out and was more reasonably priced. Robert had visited Denis’ castle and said it was très ravissant — quite ravishing — and home to a dozen painters living in an artist commune.

Knowing artists as I do, I silently wondered if there would be any wine left.

We made plans to meet up at Caf' Conc' the next evening, and in the meantime I called everyone I’d known since kindergarten, bragging that I was going to a castle with two handsome Frenchmen to drink bottles of $1000 wine.

The Turning Point

The next night, I waited and waited and waited at Caf' Conc', until it was painfully obvious that Philippe and Denis were standing me up and guzzling their stupid $1000 bottles of Bordeaux with somebody else.

I nearly started crying.

Everyone stopped by to express their condolences.

Gerard said, "Non très bien?" and mimed tears from his eyes.

Robert bought me brandies. "What do you expect?" he said. "They are Frenchmen!"

The Moulin Rouge dancers simmered, telling me Philippe was the worst kind of French playboy who’d broken hearts all over town. I wrote Philippe a scathing note and sealed it with candle wax.

Except for that night, I was in love with everyone there (except Philippe and Denis, henceforth absent as was the mongrel Gypsy), but even more with Caf’ Conc’, this character-rich, merry scene where I seriously considered dropping anchor for the rest of my life.

Every day, one or another of my new pals took me to their favorite haunts. Rosan, a leggy brunette with topaz eyes and a sweet smile, bought me lunch at a posh restaurant, where the lasagna was served in a copper pan and came bubbling in béchamel sauce; she urged me to move to Montmartre, though warned that rents for cold water flats cost far more than a bottle of Philippe’s wine.

When I ran into Henri, he took my arm as he threaded through the maze of a flea market, where he rummaged through albums and old cameras.

Buying a baguette which, as is typical, he carried without bag or plastic wrap, Henri ran into friends outside the patisserie. It was then I realized the utility of this long narrow loaf. Henri used his baguette for gesturing, for pointing, for waving, I kept waiting for him to brandish it as a sword and wouldn't have been surprised if, when he walked off, he used the multi-purpose baguette as a cane.

Sam took me to a mustard-colored café plastered with pictures of French movie stars and bought me pastis, the anise-flavored liqueur that clouds when you add water. Daniella showed me her favorite parfumerie, where the woman sprayed liquified spices and flowers from crystal bottles and we sniffed neutralizing coffee beans between scents.

Even Paco, the DJ who wore sunglasses whatever the hour and state of the sun, finally thawed: whenever I saw him on the terrace of his favorite café — next to a butcher shop where yellowed chickens dangled, their bedraggled heads and gnarled claws still intact, he yelled over, "Come Melissa! Sit with us! I buy!"

And at night, we all met up for more boisterous talks and more disco. My planned two days in Paris quickly turned into four, then a week, until finally, after ten days of dancing until six, I forced myself to carry on.

Au Revoir Paris, Ciao Venice and Prague

I took a night train to Venice, the Neptunian city of dreams sinking into the sea. Although surreal and enchanting, I discovered Venezia has hardly any nightlife, at least outside of the honeymoon suites. I felt idiotic wandering through its romantic alleys alone, passing goo-goo-eyed lovers in gondolas, the sound of “Amore” echoing from under bridges.

Although I did have one rousing evening of singing with gondoliers in a hazily lit square, I soon traveled on to Prague, a city that sounded so intoxicating that the previous year I’d almost moved there sight unseen.

Upon arrival in the eerily beautiful hometown of Kafka, its bridges and hilltop castle swathed in a swirl of fog, I was quickly disillusioned.

"Negotiate the price with taxi drivers before you get in," the guidebook said. So I did. But once we got to the destination — whether tea house or Golden Lane where alchemists once toiled and boiled their brews — the rate routinely quadrupled. And between the naked lady pictures dangling from their rearview mirrors and the cabbies' lecherous grins intimating that I could work off the price difference, I paid up and hopped out.

I almost forgave Prague for its thieving taxi men because the city was stunning in that gold-domed, forbidden, treasures long-hidden Eastern European way; just crossing the romantic Charles Bridge and looking onto the skyline of dramatic towers, the slender spires of the castle rising in the distance, was enough to make me want to live there, if I overlooked that the marble statues lining the bridge were now dressed in graffiti.

The show-stopping 15th-century astronomical clock in the cobbled main square, where a devil and the apostles whirled out on the hour, was likewise less charming when I read that the clock’s designer had been blinded by the town’s councilmen to prevent him from making such a masterpiece for any other town.

Heralded as the happening European scene in the American press, Prague soon felt melancholic, frosty, and bitter to me, the scars from Soviet-styled Communism still fresh. Young Americans — snotty, silver-spooned types — seemed as plentiful as the natives. They’d bought up buildings all over town and a cloak of anti-American resentment hung in the air.

Most locals did not speak English. When I tried speaking Russian, the fiery ice in their eyes told me more of the Soviet era and Prague Spring than any history book ever could.

The Ice Thaws, Briefly

So at a dim swankster bar with low couches and floor pillows, where I sipped a glass of the fabled (and mouth-burning) absinthe — legal there — I was relieved to meet a cherub-faced American journalist, Richard, who'd lived in Prague for three years. Richard said he and his girlfriend would show me the town for my article about European nightlife.

Then he introduced me to Zlad, a great hulking Serb with greasy black hair and a contemptuous expression. The journalist assured me that Zlad was a "great guy" and a frequent source for his articles. "Trust me," Richard said, "Zlad is who you want as a guide. He knows all the hot spots, he knows the true Prague." So when the journalist and I made arrangements for the next night, he invited sulking, hulking Zlad to come along. Alas.

A Chilling Night

The next night I discovered two things, both disturbing: My black jacket was missing — I must have left it in Venice. And the journalist was not going to show.

Instead, Zlad was waiting. "Richard can't come," Zlad told me. "He asked me to show you around."

Zlad’s first suggestion: his apartment. I emphatically declined, saying I needed interesting clubs for my article. Then he suggested a club with live sex acts. I told him to forget it and was walking away, when he ran up assuring me he had the perfect place — with live music in a bohemian setting, I would love it.

So we got in a cab, Zlad telling me how hip this club would be, and we drove out of the old city, into the creepy Communist-era parts, where the buildings were all concrete high-rises that needed only barbed wire, searchlights, and machine gun-touting soldiers to complete the disturbing effect.

"Ah, here is the club!" said Zlad, and we got out.

As the taxi soared off, I looked around: no club, no restaurant, no café, no store, no phone booth. Only a lonely boulevard along which cars full of men were cruising as if looking for prey.

"Where's the club, Zlad?"

He started laughing. "Actually, this is my apartment!"

I started screaming at him and a look of shame crept across his face.

I gazed up and down the dark boulevard. Not a taxi anywhere. And I doubted there would be a taxi: this was not a touristic part of town, if it was even still Prague. I recalled an alarming item in my guidebook: "Prague has the highest sexual assault rate in Europe..."

As if reading my mind, Zlad said, "It's dangerous out here. Come in, I will call you a taxi."

I yelled at him some more — threatening that if he pulled anything, I'd call the journalist and ensure that Zlad became headline news. And then, praying madly, I went in.

We climbed many precariously curving stairs, and once in Zlad's stark apartment, he flashed a let's-get-cozy smile.

"I love American women!" he began, stretching out on the couch.

"Zlad, just call me a taxi!"

At this Zlad's smile pulled tight, he got up, and picked up the phone. And handed it to me.

"Fine!" he said. "You call!"

I pulled out a card with the taxi service number, thinking I'd request a cab in Russian, and hoping the dispatcher wouldn’t slam down the phone.

"What's the address, Zlad?"

"I'm not telling!"

So I ran out the door and into a pitch-black hallway, where I felt my way in the dark down three sets of very hazardous stairs, not knowing that unlike in the US, where apartment hallways are always lit up, in Europe you have to turn on the lights manually.

Zlad peered out, and seeing my struggles, let out a laugh befitting of Lucifer and slammed the door.

My heart was rattling and I feared Zlad would grab me, or I’d fall down the stone stairs, or be assaulted instantly once I got out on the ominous street that looked like a scene shaken loose from Mother Night.

Luckily, a taxi came by after five minutes, and even though it was on the far side of the boulevard, my hysterical screaming prompted the driver to whip right around and pick me up. And I liked this cabbie: His taxi was not filled with photos of nude women, and he even spoke with me in Russian, apologizing over and over, saying all people in Prague weren't like Zlad.

The other good news was that this taxi driver charged me the locals’ rate — $5 for a thirty-minute ride to my hotel. I gave him $50, grabbed my bags, and hightailed it to the station to catch the next train to Paris.

As the train roared through the German countryside past dense forests and dreary cities, I thought only of Caf' Conc' and my missing black jacket. Wherever my jacket was, it had evaporated as thoroughly as my dreams of moving to Prague.

Paris Again

I returned to Montmartre, immediately heading back to Caf’ Conc’ to pick up where the party left off. Upon my first step inside, it was obvious: the party was over. Instead of the usual twenty or thirty people standing around there were three, including two employees.

The Moulin Rouge dancers had stopped coming by after work; they'd found new beaus. Jean-Paul, who'd waltzed with me on the sidewalk, had shipped out to sea. Sam, who sported a black eye, was surly and more conspiratorial than usual and now had a bodyguard. He'd gotten into a fight with Henri, who now had a broken hand and was avoiding Caf' Conc'. Kenny, the previously charming British jazz musician, was now simply a hideous mooch, pulling a chair up to my table just as dinner arrived, his pro-American sentiments — "You Yanks saved our arses" — apparently entitling him to eat off my plate. The cheery owner Robert hardly stopped by.

Worse, claiming that he wasn't getting paid, Paco had shut down le disco.

Like many of the key players, the DJ — like my jacket, like the goodwill that once filled Caf' Conc — seemed to have gone the way of Atlantis and vanished. My mood followed suit and sunk.

What the scene lacked in joviality, however, was nearly made up for by the kitchen. Gerard — who still came out asking "Très bien, Melissa?" — served me portions that towered higher each night, so I didn't mind so much when Kenny dug in. But even gargantuan servings of fine food couldn’t negate the fact that in the few days I'd been gone the whole damn scene had collapsed.

Gypsy Returns

My penultimate night in Paris, an evening so dreary at Caf’ Conc’ that even Kenny had gone elsewhere to bum dinner scraps, I looked up to see Gypsy, the mutt of Philippe.

“You!” I said, pointing at the Frenchman.

“No, you!” he said, pulling up a chair. “You have ruined my life in Paris!”

Philippe said he’d been rotisseried every day since I left. “In every café, at every party, every time I stop my car at a stoplight, someone comes over yelling at me for breaking the heart of that sweet little American! People that don’t even know you, people that I don’t even know, have been screaming at me from every corner of this city!”

And my candle wax-sealed letter, he claimed, had wounded him deeply.

I couldn’t hide my smile.

Philippe wore his guilt well, and made up for depriving me of the castle and thousand-dollar wine by giving me an impromptu tour through the city.

A Late-Night Adventure

We started out in a candlelit bar where wire spirals held up hard-boiled eggs and the only music on the jukebox was Serge Gainesbourg, the gravel-voiced Bob Dylan of France. We stopped in a hazy but hopping jazz club where the air was so thick with smoke that oxygen masks should have popped out, and the velour couch was so close to the screeching horn section I could see my reflection in the sax.

We drank champagne on the marble steps of Sacre Couer looking out over the city glittering through the inky night. We strolled under the Eiffel Tower and past Notre Dame, its sculptural lace illuminated by a blue-tinged full moon, and then we wandered along the river, stopping at the home of the man who invented the multi-use baguette — a discovery so important that a brass plaque bears his name.

"And now I will take you to where I once lived," said Philippe as we hopped back into his chocolate-brown Mercedes and Gypsy jumped into her now-customary viewing spot -- my lap. "It is the most beautiful building in Paris —ohh la la, you will see!"

So we wound around the curving streets of an outlying arrondissement, the smell of baking bread drifting from bakeries as the first fingers of sunlight pushed through the blackness.

"You will not believe this!" said Philippe as he turned down a stone street so narrow I didn't think his Mercedes would fit. "Perhaps I will ring an old neighbor so you can see inside. I have not been here for too long. It is incredible!"

Philippe turned down another side street, this one ever skinnier, then slammed on the brakes.

I expected another "Oh la la," but instead he wailed, "OH MY GOD!"

There shooting up before was an ugly, gray concrete condo.

"It is gone!" he cried. "Goddamn Chirac and his developer friends. They are destroying this city!”

For the next hour, Philippe was both despondent and furious, screaming about then-mayor (soon to be president) Chirac, who Philippe said had sold his soul to real estate men.

"It is not the City of Light anymore," he said. "It is the city of glass and concrete and modern despair."

"You know," said Philippe after he’d showed me several more cold, industrial-age monstrosities and concrete condos, "this is it! I can not sit and watch the destruction of this beautiful city. I am going to move! Finis!"

And with that his mood greatly lightened.

"Now," he said, reaching over to pat Gypsy's head, "we are going someplace very special. We will go to see Jim Morrison, the most famous American to be buried in Paris!"

The weary watchman was just opening the gates as we drove up to Cimetière du Père-Lachaise. At the risk of sounding morbid, I found this mammoth garden-like cemetery quite lovely, deciding that one of the smartest things that Jim Morrison ever did was die in Paris so he could be buried there.

The French aren't content with mere gravestones; their resting places are brimming with statues and sculptures and strange sitting-room chambers next to the graves and sepulchres and crypts where the whole family is laid out under stone. In the same way that the French polish up English to make it sound quite romantic, they present death in a manner that seems most refined.

Philippe led me to the burial place of Colette, dripping with flowers, and then Chopin’s, where sheet music rattled in the morning breeze. The flashiest was Oscar Wilde's, an Art Deco design of an Egyptian etched in its face. Roses and daisies, bottles of booze, wrinkled and mildewed books were piled before it, as if to atone to the man who died a pauper.

Disappearing Act

"And now," said Philippe, "we shall see the grave of the greatest American, Jim Morrison." I didn't mention that I wasn’t wowwed by Morrison’s repetitive lyrics, which I was prone to mock at parties.

"Yes, he should be right here!" said Philippe turning down a row of lichen-blanketed graves, many bearing monuments, as I hummed "Riders on the Storm."

"Or perhaps he is here." Philippe led me down another row of ornate graves as I hummed the lofty-minded "Light My Fire." After an hour of searching, we still could not find Jim and I had exhausted my repertoire of Doors’ tunes.

"But I swear Jim Morrison is usually buried here!" said Philippe, while I razzed him, saying Jim couldn't have just walked away.

“This is true,” said Philippe, thoughtfully. “But he may have been stolen.”

A Must-See Paris Ritual

Near the Louvre, we stopped at a sidewalk café and tossed back a café au lait. As we were about to leave, there was a sudden screeching of brakes and the sound of metal meeting metal. Right before us, a delivery van had physically bonded with a shiny red Jaguar.

"Oh a wreck!" said Philippe, clapping his hands together and sitting back down. "This is my favorite thing about Paris! We must take another coffee and watch!"

It was merely a fender bender, nobody hurt, but the long tail of traffic knew what to expect. The drivers all turned off their cars, pulled out their phones, and smilingly ran over and sat at sidewalk tables to watch.

What unfolded was a slapstick comedy, making me understand why the French love Jerry Lewis so.

First, the driver of the Jag went to the door of the van — and the driver would not get out or roll down his window or communicate in any way. Then the Jaguar driver went to assess the damage, gesturing unkindly at the van driver and screaming. Then he returned to his car and made a call on his phone.

Then the van driver got out, looked at the damage, and he screamed the same things and made the same wild gestures. Then he went to the window of the Jaguar and the driver would not get out or roll down his window or communicate in any way.

"Isn’t this great!" said Philippe, chomping into a croissant.

Finally, they both met at the dented fender and yelled and screamed and wildly gestured for twenty minutes. Then they both laughed, slapped each other on the back like old pals, and hopped back in their vehicles and all the bystanders ran back to theirs, and the morning proceeded as usual.

“It is always like that," said Philippe, wiping powder crumbs off his mouth. "If you understand a wreck here, you understand Paris!"

Last Night, Last Day

It was nearly noon when Philippe dropped me back at my hotel, and we made plans to meet at Caf' Conc' that night, my last. That evening the word had gone out that I was leaving, and many of the old crew, including the Moulin Rouge dancers, stopped by to bid me adieu, making it nearly as rowdy a night as was common not long before, though minus the dancing, since Le Disco remained closed and Paco was still MIA.

Gerald heaped my dinner so high it could barely stay on the plate, Philippe brought a rose, everyone plied me with drinks. At six, when the bartender kicked us out, my notebook was filled with numbers, addresses, wine spills, French poems, and doodles, and everyone kissed me goodbye on the cheek the French way — three times for good luck.

The next afternoon, I packed my bags trying not to think of my missing black jacket. Oddly, the jacket mirrored the scene at Caf' Conc'. I'd searched for both for years, finally found them, only to lose them again.

Both the jacket and the scene — like travel itself — seemed intangibles that could never really be owned, just experienced briefly.

“C'est la vie,” I thought, looking at my word processor, a cheap number that worked only on European current. I didn't want to bring it back home, and considered leaving it for the housekeeper.

Walking up the snaking streets of Montmartre, lightly veiled in fog from a chilly afternoon rain, I ran into Paco, the newly unemployed DJ.

"Paco," I said, "I come back to Paris to dance, but you closed le disco. It was my favorite dancing place ever."

I'm not sure he fully understood, but his face lit up, even more when I gave him a twenty for all the fun his disco parties had provided.

I felt honored when Paco invited me for coffee at his apartment.

Until I walked into the sad hovel.

Paco’s apartment was actually a cage, a tiny dump with a loft and layers and layers of clothes hanging from the walls. There was only cold water and it rented for $1000 a month.

Within minutes, the situation turned awkward. Paco spoke little English, I spoke less French. Fortunately, his roommate Henri soon arrived, sporting his fabled broken hand, of which he had little to say except, “Sam! Some friend!”

Like Sam, Henri spoke spine-tingling English. He quickly went off on a brilliant discourse about European politics, and then the media, and I suggested he write an article.

"Ahh, if only I had something to write with," Henri said with a sigh.

"You want a word processor?" I asked.

"Of course!"

"I'll give you mine."

"Are you joking? Well, come on, let's go."

And it was when I stood, and looked more closely at the many layers of clothes hanging from Paco's wall, that I saw it. What had been hanging directly in front of me for the past hour.

My jacket.

I snatched it from the wall, as though reuniting with a long-lost friend written off as forever departed.

Paco said he'd found it draped on a chair when he’d closed down le disco two weeks before. Not knowing to whom it belonged, he claimed, he’d taken it home, not knowing of course that he'd ever see me again or that I'd ever end up in his cage-apartment. Looking at the many garments lining the walls, I wondered if they were all perks of his freelance disco business.

And so I departed Montmartre — with my jacket, a promise to return, invitations for places to stay when I did, and a book brimming with drunken drawings and odd stories.

And I left changed — with the knowledge that life, predictable though it may seem, can be strangely magical. Though perhaps a little more so in Europe.

From Global Party Crasher, one of my memoirs.