The curse of the Nobel Prize: the cases of Albert Camus and Karen Blixen

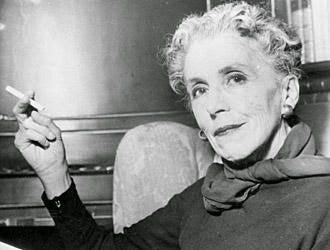

The witchy author of "Out of Africa" believed she would win the 1957 Nobel Prize for Literature, but it instead went to young Albert Camus, whose life did a nosedive shortly thereafter.

On Thursday, Oct. 5, the Swedish Academy plans to announce the winner of this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature, the world’s most prestigious honor for writers — and one of the most profitable with a purse of around $1 million.

And, as happens every year to me, the Nobel announcement evokes Isak Dinesen — the pen name of Danish baroness Karen Blixen — best known for her memoir Out of Africa, which was made into a lovely 1985 movie starring Robert Redford and Meryl Streep.

The baroness comes to mind not because Blixen won the world’s most prestigious literary award, but because she didn’t win it — and because I often think of the fates of those who beat her out in the years she knew she’d been shortlisted.

On Oct. 28, 1954, when a New York Times reporter telephoned Ernest Hemingway, requesting a comment about just winning that year’s Nobel Prize for Literature, his reaction was memorable.

“I would have been happy — happier — today if the prize had gone to that beautiful writer Isak Dinesen,” Hemingway began, also mentioning two others who’d been Nobel Prize contenders.

Was Hemingway simply being magnanimous? Perhaps.

Or had Hemingway been tipped off by his good friend, the late Bror Blixen, to be wary of his ex-wife Karen Blixen, who dreadfully longed for the medal and was not someone you wanted to vex?

Did Hemingway know that the Baroness told friends that she’d sold her soul to the devil to become a famous writer or that they considered her a witch? That in Africa she’d bitterly fought with Denys Finch Hatton — who was leaving her for another woman — just before he died in a fiery plane crash? That bad things, she claimed, befell those whom she cursed?

Whatever prompted Hemingway’s kind words — gallantry, admiration, or fear — the Danish baroness was thrilled. His comment, she wrote to him, gave her “as much heavenly pleasure — even if not as much earthly benefit — as would have [winning] the Nobel Prize.”

It was an award Blixen would be nominated for many times. However, according to the biography Isak Dinesen: The Life of a Storyteller, Blixen was apparently aware of only two times when she was told she was the most likely to take it: 1957 and 1958. And trouble certainly befell the two writers that snatched it those years, at least one of whom had help from the CIA.

“Witch, sibyl, lion hunter, coffee planter, aristocrat and despot, a paradox in herself and a creator of paradoxes, a desperately sick but indestructible woman, she steps forth from these pages with all the force of legend.” — From the New York Times review of the biography of Dinesen by Judith Thurman.

Karen Blixen, born in 1885, failed with her coffee farm operation in Kenya and her romantic life was tragic: she’d married the twin of the man that she loved, and her husband gave her syphilis, then incurable. The mercury and arsenic used to treat the disease left her in severe pain for the rest of her life — she may have been suffering from the effects of heavy metal poisoning — but she never stopped writing, or at least dictating to her loyal assistant, Clara Svendsen.

Whether due to Lucifer’s help or not, Blixen was talented, her descriptive skills captured in haunting short stories set in 19th-century Europe of sibyls, pirates, ghosts, and the occasional monkey. Margaret Atwood praised her “elegant prose,” Eudora Welty called her tales “the last outreach of magic,” and filmmaker Orson Welles was a fan, making a movie of “The Immortal Story” in 1968.

Her collection of supernatural stories, Seven Gothic Tales, was published in 1934 becoming a Book-of-the-Month selection, selling millions, and was soon followed by her acclaimed memoir Out of Africa, also tapped as a Book-of-the-Month, as were three other of her books. Blixen’s later works continued to enchant, particularly “Babette’s Feast” published in 1958 — and made into a sumptuous movie three decades later.

Blixen was first nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1950, the year it went to Bertrand Russell, and several times afterward, but in 1957, she was led to believe victory would be hers.

According to her biographer, when a famous Swedish journalist traveled to her Danish estate for an interview just before the 1957 Nobel winners were announced, she was certain that she had clinched the award — all the more when he assured her that she was the favorite among the judges.

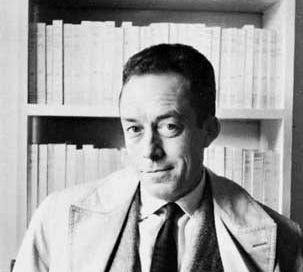

As she sat before the radio on the evening of Oct. 17, 1957, holding hands with her assistant Clara, the crackling voice of the radio broadcaster announced the news: the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature would be awarded to…Albert Camus, then only 43. He was the youngest wordsmith, after Rudyard Kipling, to ever win it.

One can only imagine the response of the sickly 72-year-old baroness at the news.

Born into a poor family of colonial farmers in Algeria, chased out of the country for his articles about the underclasses, and moving to France just weeks before the Nazis invaded in 1940, Camus was himself noteworthy and accomplished: he’d been chief editor of an underground resistance paper in occupied Paris, and he was the first writer to publicly condemn the 1945 use of the atomic bomb, pointing out while Hiroshima still burned that since we could now wipe out cities with weapons the size of soccer balls that civilization had entered its “ultimate phase of barbarism” and now faced the very real possibility of “collective suicide.”

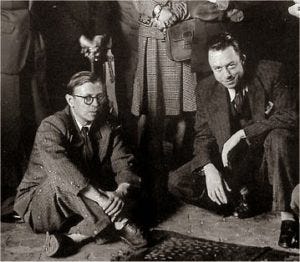

Previously close with philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and feminist Simone de Beauvoir — the Parisian king and queen of the literary elite — Camus had published a handful of novels, most notably The Stranger, The Plague, and The Fall as well as absurdist philosophical tracts, such as The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel.

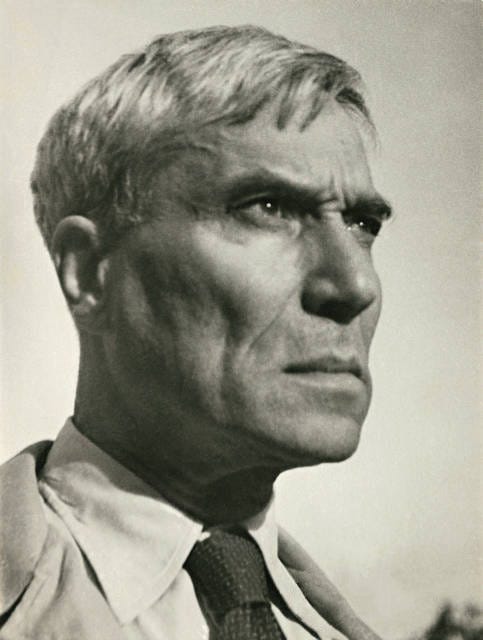

When asked about his response to winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1957, Camus demurred that the prize should have gone to French writer Andre Malraux, also a nominee.

But Camus never mentioned Isak Dinesen/Karen Blixen, who’d been certain that she would be the victor that year.

And shortly thereafter, Camus’ life went to hell.

I’m not suggesting a causal relationship, just noting what happened.

On the upside, for the first time in his life, Camus had money — winning around $400,000 in today’s dollars — as well as gaining a mighty platform to issue calls to humanity “to prevent the world from destroying itself.”

On the downside, his award prompted chronic anxiety attacks, and in the wake of being named a Nobel laureate, Camus developed an intense and long-lasting case of writer’s block. He would never publish another book during his lifetime.

(Such reactions from Nobel laureates of all sorts, including scientists, aren’t rare, being known as “The Nobel Prize Effect.” As Hemingway once surmised before winning the prize himself, “No son-of-a-bitch who won the Nobel Prize wrote anything worth reading afterwards.”)

Just as bad for Camus: his award was scorned and mocked across Paris, where Camus — once cheered and adored — had become a pariah.

The problem was Communism: in his writing and conversations, Camus had loudly denounced Stalin’s purges, gulags, and forced relocations, saying he was no better than Hitler. His then-dear friends, Sartre and de Beauvoir, however, were loud supporters of Communism, saying that Stalin’s actions were unfortunate but necessary for Communism to flourish.

The friendship with Sartre and de Beauvoir, which Camus had cherished through the 1940s, began unraveling over the doctrine — all the more in 1951 when Camus published The Rebel, a tract likening Communists to blind followers of a godless religion that justified violent means to a dubious end. Sartre’s influential literary journal Les Temps Modernes slammed the book and the author.

In his printed reply to the nasty review of The Rebel, Camus jabbed at Sartre’s anemic contribution to the French Resistance. Sartre’s printed response accused his former friend of “pomposity,” “philosophical incompetence,” and “dismal self-importance,” concluding 19 scathing pages later that Camus had once been relevant, but was now “only half-alive.”

The war of letters evolved into a Sartre-led smear campaign against Camus that lasted through the 1950s. Winning the Nobel only spiked the ire, making Camus even more of a target for attack. “Camus was despised — by universities, by Sartre, by surrealists,” the late Gallimard editor Roger Grenier, who knew the gang well, once told me. “He was held in low esteem everywhere.”

However, thanks to his Nobel Prize winnings, Camus could afford to move — to Lourmarin, a fetching Provençale village in the south of France. He relocated to the hamlet in 1958 to escape the hissing and muttering in Paris, which included rumors that Camus’ victory was due to American influence, perhaps even on the Nobel Committee.

On that point, his critics may have been right.

As documented in The Cultural Cold War, in the years following World War II, the CIA delved into the world of arts and letters, supporting journals, publishers, and writers expressing anti-Communist ideas — and Camus, who railed in articles at what the Soviet Union was doing, had so loudly condemned their violent quashing of the 1956 Revolution in Hungary that even Sartre was forced to distance himself from Moscow. Camus’ diatribes certainly got him noticed by the CIA.

Whether the CIA or the U.S. government at all played a role in shoving Karen Blixen out of the winner’s circle in 1957 and pushing in Albert Camus is difficult to ascertain.

However, the CIA’s role in helping out the 1958 Nobel Prize winner is well-known.

When the Nobel Committee asked Camus to nominate a writer for the 1958 Prize, he put forth Russian poet Boris Pasternak, recent author of the novel Dr. Zhivago and another Soviet-questioning writer who was of great interest to the CIA.

One snag: to win the Nobel, writers must be published in their own language — in Pasternak’s case, Russian — and the Soviets wouldn’t print it, since they thought it attacked the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution that brought them into power.

However, in a case now well documented, the CIA had the book smuggled out of the Soviet Union and had it printed in Russian.

Boris Pasternak was thus eligible for a Nobel, and — though it’s not clear if the CIA unduly influenced the Nobel Committee or not — Pasternak won the prize in 1958, another year that Isak Dinesen had been told by the Swedish press that she would assuredly win.

It must have been doubly vexing for Dinesen when she learned the 1958 award was wasted: the Soviets wouldn’t even allow Pasternak to accept it — a move that made Moscow look draconian, to the CIA’s delight.

In Lourmarin, where he bought a former silkworm farm, the house still thick with fluttering moths, Camus was finally making some progress. He adapted Dosteyevsky’s novel, The Possessed, into a play that premiered in Paris in January 1959 to critical acclaim.

Buoyed by the response, Camus returned to the farmhouse in Lourmarin, finally writing an original work as the fierce Mistral wind blasted through the village, knocking at his door and rattling his windows like an unseen demon.

Through most of 1959, he often holed up there alone, composing while standing, writing with a fountain pen as he roughed out The First Man, a novel interweaving one family and two countries, France and Algeria. He described it as a modern-day War and Peace, a work he promised would be his finest.

But his post-Nobel insecurity still lingered: Camus kept burning draft after draft, week after week. When his wife Francine and their 14-year-old twins, Catherine and Jean, traveled to Lourmarin from Paris to visit Camus for Christmas 1959, Francine found him trying to torch the latest version, a mere 144 handwritten pages, but she stopped him.

It was a horrible holiday visit, his son Jean later told me, filled with fights, tears, sharp words, and talk of divorce. Camus had planned to travel back to Paris on the train with his family at the first of the year, but at the last minute changed plans when his best friend Michel Gallimard, who was also his publisher, roared into Lourmarin in his sports car, a Facel Vega. Camus hopped in the passenger’s seat, his manuscript at his side.

Camus returned to Lourmarin two days later — in a casket. Gallimard’s car blew a tire and slammed into a tree on Jan. 4, 1960, instantly killing Camus, who’d accepted his Nobel only two years and three weeks before. Seriously injured, Gallimard was in a coma for a week, waking only to ask “How is Albert?” before joining him. Camus’ incomplete manuscript, found in the mud near the wreck, was published by his twins in 1994.

A recent book suggests that the Soviets — specifically the KGB, which loathed Camus for his Pasternak nomination and his critical writing about the USSR — may have been behind the blowout, though the evidence isn’t solid.

In May 1960, four months after Camus was buried in his beloved local cemetery, Boris Pasternak, who hadn’t been ill when notified about the Nobel, died of cancer, having been awarded the prize only 17 months prior. In July 1961, Ernest Hemingway killed himself.

Outliving those winners even though she was far older, the Baroness, by then emaciated and unable to eat, passed away at age 77 in October 1962 — another year she was short-listed and appeared the favorite for the Nobel — her death making her ineligible for the cursed prize that she so desired. In recent years, the Swedish Academy has taken the rare step of saying that Blixen deserved the medal, but that the committee of judges feared that too many Scandinavian writers were winning, thus they had blocked the Dane who craved it from receiving the prestigious award.

In 1964, when the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Jean-Paul Sartre, he understandably refused it.

The 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature went to Jon Fosse, a Norwegian playwright. Which is to say, another Scandinavian.

Always loved Karen Blixen. Lately, I found a Danish movie directed by Bille August about one of her last works: Ehrengard, 1963. And there is a lot of Kierkegaard in that comedy. I guess she was expecting something in exchange for Kierkegaard's exhaustive reading and devotion that went beyond. With Carnival, The Dreamers, The Pearls and Babette's Feast. Anyhow, if the Nobel Prize ignored her because she was Danish, and they wanted to be open to other writers, like Camus or Pasternak, guess what? Marcel Proust and Virginia Woolf were also ignored!