The Sexy and Sublime Second French Empire: Part 2

Mid-1800s Paris was a swell time for courtesans and Parisian high society

The beautification of Paris, which would soon be regarded as the most dazzling city in the world, began in 1852 when the very new emperor, Napoleon III, transformed what had been royal hunting grounds and bandit-thick forests into a vast public park — nearly three times the size of Central Park in New York.

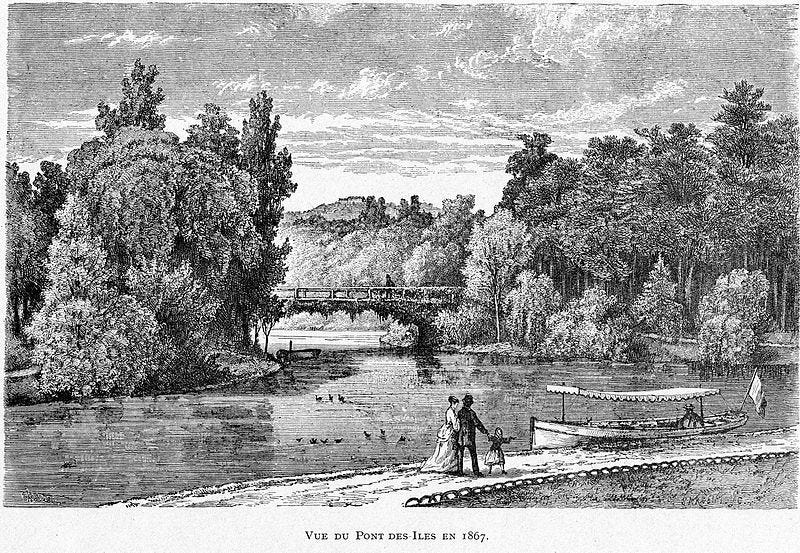

Known as Bois de Boulogne, the new green space, which included waterfalls, bandstands, and a zoo, became the hopping social epicenter of the French capital.

It wasn’t entirely wholesome.

Dotted with ponds and lakes crossed by romantic bridges, laced with nature trails for strolling or riding, and bursting with gardens — from the manicured English variety to the jungly botanical sort — “the Bois” (pronounced bwah) provided the grateful working class with an open-air escape from crowded tenements and dank alleys.

Artists, including Manet, flocked there, inspired by the picnics under the shade trees, the rowboats on the lakes in the summer, the ice skaters on the lakes in the winter, and the naked frolics through the woods any time of year.

The multi-faceted park was just as adored by the upper crust and the swelling bourgeoisie, who dined at its terraced cafes and chalet-restaurants before settling into the grandstands at the Longchamp race track, the first in Paris.

The idea for Longchamp, which was leased to the local rich man’s fraternity, the Jockey Club, was pushed through by its leading member, the slick businessman Charles, duc de Morny — half-brother of the emperor who’d masterminded his recent ascension and cashed in some chips.

But by far the biggest draw to the Bois de Boulogne, which attracted thousands of onlookers every day, was the afternoon spectacle of VIPs riding through the park, a parade of such high entertainment value that it topped to-do lists in Paris tourist guides.

The promenade began daily at 4 pm, creating huge traffic jams as elegant horsedrawn carriages entered the park for the see-and-be-seen pleasure of visiting royals, playwrights, diplomats, industrialists, composers, nobles, the Empress, and sometimes the Emperor himself.

Predictably, the beguiling courtesans, that powerful group of a dozen seductresses who became the wealthiest women in France during Napoleon III’s reign, worked this natural stage with particular elan, wanting to keep themselves in the public eye while scouting out new prey. They were self-marketed luxury items and status symbols, always wearing the latest most daring fashions — and starting new trends, from wearing dramatic stage makeup to coloring one’s hair.

Take, for instance, the most famous and stylish of the so-called cocottes, Cora Pearl, formerly a hat maker in England, who’d arrived with her dance hall owner boyfriend in the mid-1850s, being lured by the stories about the so-called “magician-emperor” Napoleon III and his sparkling renovated Paris, the most enchanting city on Earth, according to British Queen Victoria herself.

After a month of him wining and dining her in the fabulous restaurants now lining the new boulevards, spending heftily in jewelry stores and the just-opened haute couture boutiques, and browsing the world’s first department store, Le Bon Marche, between boat rides on the Seine and the afternoon “Who’s Who” parades through Bois de Boulogne, her boyfriend announced it was time to return to England.

Cora objected — tossing her passport in the roaring fireplace of their hotel suite; he left, and she stayed, along with the jewelry and dresses he’d just bought her.

Hiring a “social agent” who introduced her to princes and dukes, she quickly signed up several as her “protectors.” In turn for her regularly scheduled attention and affection, they gifted her dazzling jewels, handsome horses, and fabulous villas — even paying for her household staff and live-in chef, said to be the finest in France.

Never a classic beauty, Cora nevertheless was a lively, informed conversationalist, and had both an alluring body and audacious wit, becoming as infamous for the all-night soirees at her villas and her appearances at costume balls clad in little more than Eve, as her skills in the sack. She stood out in the daily promenade, always modeling a smashing hat and dress — often with her hair and her lapdog’s fur dyed to match — from the new House of Worth, which gave her dresses for free knowing that where Cora went, eyes followed. Often she rode in her carriage unaccompanied, until then taboo, and tossed flowers to the many onlookers who called out her name.

Even though Emperor Napoleon III censored the press and sent out “morality police” — who shut down plays and banned books for lewdness — he turned a blind eye to the promenading courtesans, who were more kept women than mere prostitutes, the latter who were legal and registered in Paris during the Second Empire and subjected to weekly medical exams.

Courtesans, whose “protectors” were always wealthy and titled, skipped that rigamarole required for common prostitutes, and their splendid homes, filled with fine art and servants, weren’t brothels where clients rang; if a courtesan was interested in the latest ambassador or dashing prince in town, she sent an invitation for a formal dinner in her resplendent mansion.

In fact, as Napoleon III realized, the presence of the famous cocottes in the promenade only added more color to the park scene, which quickly became world-famous. The rip-roaring success of Bois de Boulogne in the west of Paris, soon followed by the even bigger Bois de Vincennes to the east, were early feathers in the cap of Louis-Napoleon — nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte — who had in 1848 been elected to lead the country as it first president. His inability as president to create Bois de Boulogne, or to push any of his urban renovation plans through a parliament that loathed him, had compelled President Louis-Napoleon to overthrow his own government and change his title to Emperor Napoleon III.

While most accepted this change of government with a shrug, his December 1851 coup d’etat had provoked riots in some quarters of Paris, with writer Victor Hugo among those who manned the barricades and fought the police, before fleeing to Belgium in protest. Others who resisted were exiled to Algeria.

But one high-profile protester benefitted from pushing back: Plon-Plon, the son of Jerome Bonaparte and cousin to Louis-Napoleon, whose coup d’etat he loudly opposed. However, Louis-Napoleon, who’d bought his Uncle Jerome’s support with high titles and palaces, finally won over Plon-Plon, making him Prince Napoleon, heir to the throne, paying him generously via the civil list, giving him the grand living quarters of Palais Royal as his digs, throwing in the royal yacht and a hunting lodge as well as putting him in charge of planning world fairs.

Plon-Plon’s sister, Princess Mathilde, who’d once been engaged to Louis-Napoleon, supported the coup. She requested only that her live-in lover Emilien Nieuwerkerke be made director of the imperial museums, a move abhorred by outsider artists, like Manet, as we will later explore. The emperor gifted her a mansion, the site of her weekly art and literary salons, in gratitude for her role during his presidency, when she’d served as his de facto first lady, since the president’s paramour, Harriet Howard, was hidden off to the side, being a courtesan herself.

But when the Louis-Napoleon proclaimed himself emperor in 1852, a courtesan just wouldn’t cut it for an empress. He needed a woman with a royal pedigree. Alas, none of the major royal houses in Europe would approve a marriage to this latest Bonaparte upstart, so he ended up with Eugénie de Montijo, a countess from Spain, whom the emperor wed in 1853 after the briefest of courtships.

The emperor named his favorite courtesan Harriet Howard a countess, paid her a hefty sum, gave her a castle, and shipped her off, never again seeing the woman who was the true love of his life as he had promised Eugénie.

But that didn’t mean the Emperor no longer gallivanted with courtesans, the equestrian Margaret Bellanger being among those who soon followed. Eugenie was furious, but like almost every other wife of a wealthy Frenchman, there was little she could do but try to ignore the cocottes and their world.

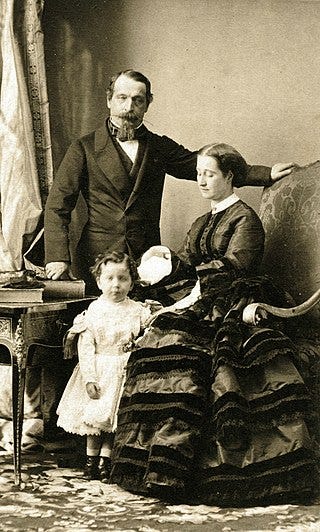

The existence of this shadow reality set up an absurd social dynamic. Courtesans’ benefactors had wives and families, but that life was compartmentalized and often shoved to the side. These cocottes offered rich men escape into the luxurious, frivolous, and alluring demi-monde, as courtesan society was known, being a parallel world of great food, scintillating banter, wild parties and antics, and memorable romps in the bedroom. Courtesans, the most independent women in French society, were begrudgingly accepted, but not officially acknowledged — they couldn’t sit in the same church pews as high-class women and they weren’t invited to royal balls, for instance — despite being extremely influential and a source of secret awe.

If a high-society woman encountered a noble acquaintance with a cocotte at his side, she was to pretend she hadn’t seen him — and vice versa. Acknowledging a woman of status while in the company of a “demi-mondaine” was a grand faux pas, as a new diplomat to Paris quickly discovered: while riding with a courtesan, his carriage passed that of the empress, and he raised his hat and bowed his head — causing a scandal as a result.

And during the 1850s and 1860s, courtesans had plenty of wallets to lighten. With the glittering renovated city being unveiled by the emperor, whose financial support spurred technological leaps and brought 15,000 miles of train track and telegraph wires crossing France — and who also staged two major world fairs, big deals in those days, that were attended by millions — the moneyed crowd was racing to Paris by train, by carriage, by steamer boat to revel in what even British Queen Victoria called the most enchanting city on the planet.

The emperor hired Georges-Eugène Haussmann, an administrator with engineering know-how, to transform Paris into “the capital of all capitals.” Haussmann knocked down dark medieval quarters and opened up the city, creating wide tree-lined boulevards that made for orderly traffic and mandating that new buildings along them be uniform in design — with stone facades, wrought-iron balconies, and Mansard roofs.

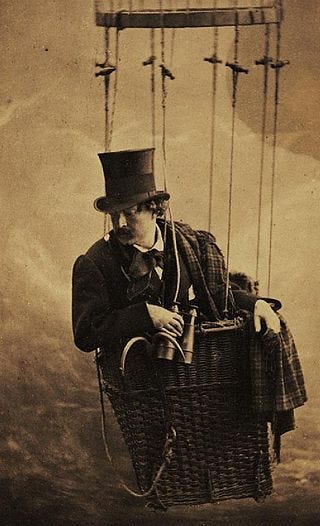

He built aqueducts to bring clean water into the city where until then water — for cooking, cleaning, bathing — had been delivered on foot. Gas mains brought lights to homes, theatres, and streets. and glass-and-iron train stations and bustling markets opened their doors, while a green necklace of more parks and more squares appeared across Paris. Photography took off — the courtesans popularized photo calling cards — and aerial photography was born with Nadar, who shot pictures from his air balloon.

Due to phenomenal tourism, increased foreign investment, and loose banking practices, the money kept pouring into Paris, where the merchant class swelled; and, as usual, the rich kept getting richer thanks to booming businesses and land speculation. Gambling, debauchery, and vice snaked through the scene, helped along by the emperor’s half-brother, Charles, duc de Morny, a conspirator in Louis-Napoleon’s coup d’etat, who was made president of the lower house of parliament.

A few hours northwest of Paris, de Morny founded a seaside gambling town, Deauville, famous for its racetracks and casino, which became another decadent playground for nobles and the well-heeled.

Culture was bursting at the seams — the well-to-do, including Princess Mathilde, held weekly salons to discuss art, books, and politics; costume balls were frequent and well-attended; Offenbach’s operettas and music made can-can the rage; millions poured in to savor the refined (and sometimes scandalous) works at the annual Paris art salons where thousands of paintings were hung to the ceilings; fantastic restaurants abounded and orchestras played free concerts in the parks — and with pockets fattened with new wealth, and the emperor’s beautification efforts astounding both Parisians and visitors, the imperial charade of the Second French Empire, which lasted 18 years, became the most opulent and luxurious era France had known.

But as we will explore in Part 3, the empire was marred by depravity and weakened by ridiculous wars, which ultimately brought the beautiful facade crumbling down.

Did you miss Part 1 of this series? Here’s the link.

Nicely done, Melissa. And profusely documented. I guess the golden era of the French courtesans is long gone, instead we have these cheap and ridicule celebs, second rate royals, and nepo babies without any single merit, besides infesting the tabloids with nonsense, victimization, and mediocrity.