The Three Napoleon Bonapartes

Kicking off the "Boning up on the Bonapartes," this post reviews the lives of Napoleon I and the two Napoleons who followed

When most people hear the name Napoleon, one person springs to mind. This guy.

Born on the island of Corsica, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) is shown here in his Paris palace shortly before invading Russia, his most profound mistake. The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries by Jacques-Louis David, 1812.

In fact, there were actually three famous Napoleon Bonapartes who lived during the 1800s, all emperors of France, two of whom dramatically altered the destiny of their country.

Who’s Who?

The first Napoleon was the brilliant military leader who conquered most of Europe. Napoleon II was but a toddler, being his long-awaited son. Napoleon III was his nephew, a starry-eyed dreamer turned escaped convict who as emperor accomplished far more than his uncle, bringing the unfulfilled dreams of Napoleon I to fruition.

The Three Napoleons: Napoleon I. Circa 1807. Napoleon II, age 7, in a painting, circa 1818, attributed to Johann Peter Krafft, M.S. Rau. Napoleon III in an 1862 work by Jean Hippolyte Flandrin.

The Ascent of Napoleon I

The rise of the three Napoleons started when the first one orchestrated a bloodless coup d'état in 1799 in Paris. This act marked the end of a tumultuous and bloody decade initiated by the French Revolution, a period marked by the fall of the monarchy, the establishment of a republic, and the execution by guillotine of 15,000 French citizens, including King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette.

Wary European monarchs, not wanting to see what happened to the French monarchs repeat in their countries, sent out troops to quash the revolutionary spirit, leading to battles that France initially lost. However, after the young general Napoleon Bonaparte galloped onto the scene in 1793, France claimed victory after victory.

In the last days of the 18th century, Napoleon, freshly arrived from Egypt, his most recent conquest for France — a victory that would soon evaporate — returned to Paris and overthrew the government. Called the “Coup of 18 Brumaire,” the Nov. 9, 1799 ouster established a three-man ruling consulate. As First Consul, Napoleon reorganized the country, created a professional army, and negotiated a brief peace with France’s fiercest foe, Britain.

Then he tweaked his title, becoming “First Consul for Life.”

The Ruler-for-life Needs an Heir

As his wife Josephine had not borne any children by him, Napoleon devised a novel succession plan in 1802: he forced his younger brother Louis to wed Hortense Beauharnais — Josephine’s daughter from a previous marriage. It was an unhappy union, but Hortense soon gave birth to a boy. However, Louis’ siblings convinced him that the child was actually Napoleon’s.

Louis’ fears were not assuaged when Napoleon announced plans to adopt the child, Napoleon Charles. Before that plan was realized, however, the boy died from croup. Hortense bore two more sons whose suitability as heirs was evident in their names — Napoleon-Louis and Louis-Napoleon — but by then Napoleon simply wanted a son of his own; besides, paranoid Louis doubted that the boys were genetically his.

Louis-Napoleon, right, shown with his mother Hortense and his brother Napoleon-Louis, later became Napoleon III and started the showy Second French Empire.

Meanwhile, Napoleon’s overseas missions were running afoul. Britain drove the French out of Egypt in 1801, even snatching the antiquities the French had unearthed, including the Rosetta Stone that finally allowed deciphering hieroglyphics.

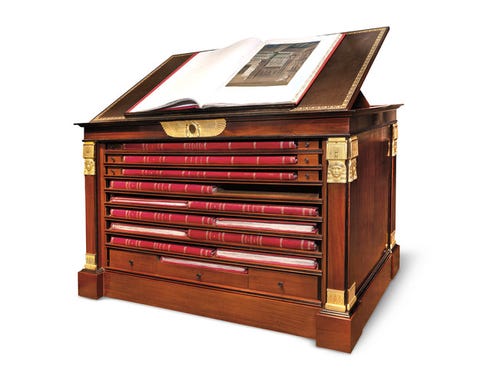

Napoleon brought over 100 artists, scientists, and scholars with him on the voyage to Egypt. Their observations and drawings were published in the 34-volume Description de l’Égypte, First Edition, Circa 1826, M.S. Rau.

Napoleon’s Overseas Operations Teeter

By late 1802, Napoleon’s plan to expand into the Americas also began falling apart. Thanks to a secret deal with Spain negotiated in 1800, France now possessed the vast Louisiana Territory, including the port of New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi River. Napoleon planned to enter through that city, then claim control of the river, and send French settlers into the fertile lands to its west.

With plans to launch his operation from the French colony of Saint-Domingue — today’s Haiti — thick with sugar plantations, he sent 30,000 troops to the Caribbean island, instructing them to subdue Saint-Domingue’s rebelling slaves and use them as soldiers in the attack on the U.S. They arrived in early 1802, but over the following months, yellow fever felled half of his troops, including their commander, General Charles Leclerc — who was married to Napoleon’s sister Pauline — and the slaves refused to fight for France.

Louisiana Purchase

What’s more, Napoleon’s war coffers were nearly tapped. In 1803 when the U.S. offered to buy New Orleans for $10 million, Napoleon instead sold them the entire Louisiana Territory for $15 million — which is how the United States doubled in size overnight.

Map showing the territory gained in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Source.

Imperial Coronation

1804 was a standout year for Napoleon: his Napoleonic Code was enacted — with new laws promising freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and trial by jury. And in May, Napoleon declared himself emperor of the French people. His lavish coronation, officiated by Pope Pius VII, took place in December at Notre Dame. Even then, Napoleon showed who was boss, grabbing the jeweled headgear from the holy man and crowning himself.

In this massive work, The Coronation of Napoleon, completed in 1807, artist Jacques-Louis David painted Napoleon’s mother, Letizia, even though in reality she was on the outs with Napoleon and didn’t attend. Source.

As emperor, Napoleon was hell-bent on expanding his empire — and conquering France’s rival Britain. His planned naval attack on Britain with Spain, however, quickly turned into a disaster, when the British preemptively attacked their fleets off Spain in the Battle of Trafalgar, crippling the French and Spanish navies by destroying most of their vessels and making an invasion of Britain a non-starter.

Even if Britain now unquestionably ruled the seas, the French army was Europe’s mightiest force on land.

Pieces on the European chessboard

Leading victorious battles in today’s Italy, Germany, Austria, and beyond, the French emperor soon controlled most of the Continent, placing his siblings on thrones in the newly captured territories, from Naples to Holland.

Beyond collecting taxes, drafting soldiers, and enforcing his civil code, Napoleon insisted that his siblings, as rulers, enforce a blockade against the British and embargo British goods, a plan known as the Continental System. Napoleon hoped the Continental System would strangle Britain’s economy, but the effects weren’t ultimately very dramatic for the British, who had plenty of other markets.

Instead, the Continental System hurt the French. Raw materials couldn’t get in, exports didn’t go out, smuggling became rampant, and across the French Empire the economy teetered.

Worse, Napoleon began taking extreme actions to enforce his blockade and other decrees. Portugal refused to cut ties with Britain, so France invaded. Spain wasn’t reliable, so Napoleon invited the royal family to France, but wouldn’t let them leave, sending troops marching into Spain to install his brother Joseph as king.

Napoleon’s First Big Mistake

Those events triggered the 7-year Peninsular War, pitting France against Britain, Portugal and Spain. It bled Napoleon of so many fighters that he referred to it as “The Spanish Ulcer” and it continued throughout the rest of his reign.

Another extreme act: Angered when the pope refused to enforce his Napoleonic Code and other edicts, Napoleon had the pope kidnapped — keeping him locked up for five years. Then again, imprisoning the pope was one way to ensure that Napoleon wouldn’t get papal flack when he remarried, which he was about to do.

In 1809, Napoleon annulled his marriage to Josephine and the next year wed the Austrian emperor’s daughter — Archduchess Marie-Louise. She gave birth to Napoleon François Charles Joseph in 1811; called “The King of Rome,” he was later briefly known as Napoleon II.

The celebrations didn’t last long. Napoleon soon turned on his former friend Russian Tsar Alexander I. Since 1807, the two had been allies. However, the Continental System devastated the Russian economy and after a few years, the tsar broke the alliance.

Napoleon’s Most Foolish Move

In 1812, Napoleon invaded Russia in retaliation. Napoleon’s 6-month Russian campaign was a fiasco: the Russian forces rarely fought the French, instead burning crops and towns before they arrived. When Napoleon entered Moscow, he found it emptied and ablaze, his troops weren’t equipped for the harsh winter, food ran out, and his soldiers abandoned him. Of the 600,000 troops Napoleon marched in with, 500,000 didn’t march out.

The Russian campaign proved his undoing since nothing was gained, and so many were lost. Given his weakened army, Napoleon was ultimately defeated by a grand coalition of European powers in 1814. Forced to abdicate, Napoleon was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba. French King Louis XVIII was installed on the French throne — and Marie-Louise and Napoleon’s son fled to her family in Austria.

Ten months later, when Europe’s leaders met in Vienna to decide how to reclaim their lost lands, Napoleon escaped his exile and returned to France, ruling for 100 days. However, his French forces were defeated in the Battle of Waterloo, which marked the end of the reign of Napoleon I.

Au revoir, Napoleon

Before being exiled to the Atlantic Island of St. Helena, Napoleon tapped his son as successor, an idea rejected by the victors. But in the fifteen days it took to get King Louis XVIII back on the throne, Napoleon II was officially the ruler of France, although the boy, then 4, remained in Austria, unaware he was emperor.

The returned French king banished all Bonapartes from France. Many relocated to Rome, but Hortense moved to Switzerland with her youngest son, Louis-Napoleon, then 7. Louis-Napoleon, who’d known Napoleon only as a child, soon became obsessed with the idea that the Bonapartes must reclaim the imperial throne.

When Napoleon died in exile on May 5, 1821, eyes turned to his son, but by then he was more Austrian than French. Known as Franz, Duke of Reichstadt, he had no desire to rule France. In 1932, at age 21, he died of tuberculosis, accurately summing up his life in his final hours: “My birth and my death, that is my story.”

The Empire Surprisingly Continues

The Napoleonic tale could have ended right there. But it didn’t. Napoleon’s quixotic nephew Louis-Napoleon took matters into his own hands and kept trying to overthrow the French monarchy. His first laughable attempt in 1836, when he marched through Strasbourg startling citizens with calls to support him, resulted in Louis-Napoleon being banished to the U.S. by the French king.

However, when his mother was on her deathbed, Louis-Napoleon returned to Switzerland. When Hortense died, he inherited a hefty fortune and moved to London, where he lived as a bon vivant.

In 1840, just before Napoleon’s exhumed remains were finally returned to Paris as the first emperor had requested, a cause for country-wide celebration, Louis-Napoleon tried to seize upon the nostalgia — and attempted another coup in Boulogne, again causing only a ridiculous spectacle. He was arrested and tried, and at age 32, he was sentenced to life in a French prison.

Disguised as a workman, he escaped in 1846, returning to London. Surprisingly, Louis Napoleon — an escaped convict who was living in England — was elected as the first president of France in 1848.

The new constitution allowed presidents to serve only one 4-year term, so at the end of 1851, Louis-Napoleon successfully overthrew his own government — claiming they were trying to overthrow him. The next year he declared himself Emperor Napoleon III and launched the opulent Second French Empire (1852-1870), the most glittering era France had ever known — during which he entirely modernized Paris, making the French capital the belle of the global ball.

La Place de la Concorde, Paris by H. Claude Pissarro. M.S. Rau.

The glitz, the glory, and the modernization continued for eighteen years, until 1870, when an ill-planned war against Prussia ended in defeat for France, pulling the plug on the Second French Empire overnight, and spelling a final end to the rule of the three Napoleons of the 19th century.

A similar version of this post appears on the M.S. Rau Antiques website.

Interesting story! Went to the Napoleon museum in Paris, this helped make it make sense!

Perfect! With this illuminating read, I feel now set and ready for the imminent Ridley Scott's film.