The Whisper Train to Paris

Long train rides used to be wild adventures. Now they're remarkably efficient, but sterile.

A train trip from Barcelona to Paris sounded festive, even adventurous, my friend Meg and I recently decided, envisioning that we’d be drinking in the French countryside over fantastic food and wine in the chic dining car. So of course we booked the 7-hour trip.

The idea of rail travel flooded my brain with memories of wonderful night trains from Paris to Florence, the trains clacking past gold-lit mountain villages as I dined on cheese and fine Bordeaux, feeling the greatest happiness I’d ever known.

Whether in Europe or the US, people on trains often told me moving stories — and bizarre ones. People like Nathalie, the young Amsterdam artist, whose thrill was taking MDMA and spending entire nights in dark train tunnels.

There was just nothing that could compare with the rush of a train roaring past you, mere inches away, while you’re high on Ecstasy in a dark tunnel — I should try it, she said.

People like the conductor who every trip waved at his wife from the caboose, as the train passed their West Virginia home, only later telling me about the time his train derailed, panic still evident in his eyes.

My memories turned to Mike, the kindly former Marine, whose wife had just left him — with their newborn twins — and who spent our entire train ride from Portland to Chicago trying to convince me I should step up as Wife Number 2. And Wendigo, the young nanny who’d just been fired after totaling the family car, who (like Mike and a dozen others) later looked me up, though only Wendigo nearly started my Portland apartment on fire.

That was the same 31-hour trip on the so-called “Empire Builder,” when I met Ivan, perhaps the most deranged, but memorable, of all the people I’ve encountered on trains.

We became acquainted in the bar car where Mike and I teamed up for rounds of “Hearts,” winning game after game.

This was decades ago — back when people smoked cigarettes, and you could even smoke them in the bar cars of trains, which now sounds totally debauched, but made for rollicking good times back then.

Ivan, with his pale skin, glasses, and short brown hair, struck me as a socially inept nerd. After 20 minutes of intently watching our card game in the bar car, which wasn’t that fascinating, Ivan finally worked up the nerve to introduce himself.

Could he bum a cigarette, Ivan asked me. I gave him one. Thirty minutes later, he asked for another. I gave it to him. When he asked for a third cigarette, I declined — noting I’d brought one pack for the entire ride to Chicago.

“Oh sorry, sorry, I didn’t know,” Ivan said, mortified. He’d pay me back, he promised. I assured him it was no big deal.

The next morning, when the train stopped at Whitefish, Montana, the conductor announced we had a 15-minute stop if we wanted to stretch our legs. Mike, Wendigo, and I were already in the bar car having coffee, and I noticed that Ivan was among those who disembarked. Just as the whistle blew, he ran back to the train.

Ivan appeared in the bar car minutes later, looking flushed, and holding a bag. “Melissa, I wanted to pay you back for those cigarettes,” he said, pulling a carton of Merits from the paper sack.

“Ivan, you didn’t have to repay me,” I said. Especially with a carton of Merits, the worst cigarettes ever.

“And I got you some candy too!” he said, dumping a mound of chocolate bars on the table. Then he took off.

“That guy is seriously weird,” said Mike, who began dealing cards.

An hour or so later, the train pulled up to the station in Shelby, Montana. Oddly, armed state patrol officers entered the train. We heard yelling, more yelling, and the sound of people running.

Then we looked out to see Ivan being escorted off the train in handcuffs.

He’d held up the tobacco stand at the Whitefish station.

“Isn’t the key to a heist confusing authorities about where you’re heading next?” I asked. Authorities had known exactly where the train-bound robber was heading.

“Maybe he planned to hijack the train,” volunteered Mike.

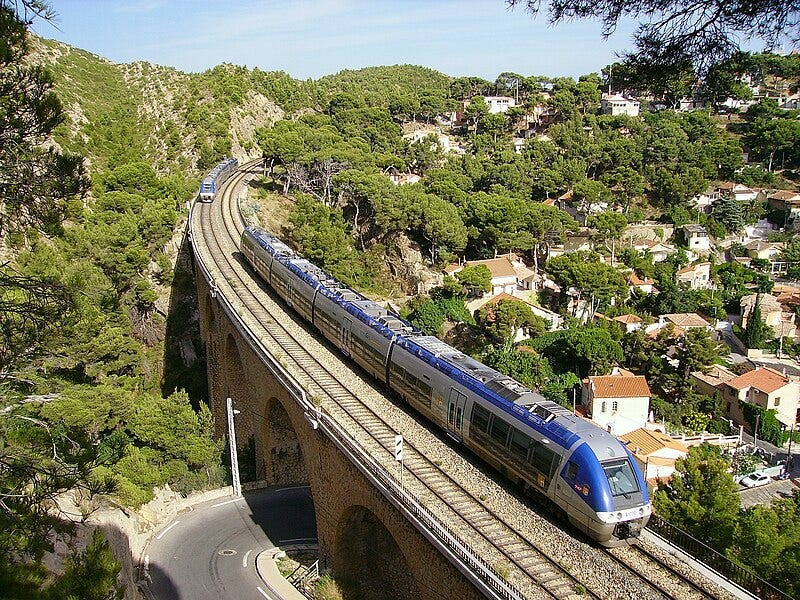

So with these and a dozen more train tales swirling around in my brain, Meg and I embarked Tuesday morning on the sleek SNCF train bound for Paris, realizing our seats were in different cars. Unlike the trains I’d previously ridden on, there weren’t closing door compartments holding four or six seats; instead, the seats were laid out two-by-two with no tables — like a commuter train.

There wasn’t a dining car, and even the snack car lacked tables, holding only a few bar stools, most of them occupied by people who weren’t even drinking or eating.

But the strange thing about the train was that it was silent. A conductor didn’t even come through asking for tickets. And none of the passengers were talking, although in the seat across the aisle from me, two women were whispering — in such low voices I couldn’t even ascertain what language they were speaking. Even in the snack car, the only sound was people putting in their orders.

Even the train itself was noise-free. It no longer rumbled through villages — it glided. It didn’t even whistle as it passed.

A few hours into the journey, I committed a faux pas and began chatting in a low voice with my neighbor. She was a cellist, I discovered, who after her last gig in Madrid was taking four trains to her next gig in Vienna. When I asked why she was taking so many trains instead of flying, she said even though the trip was more expensive by rail, she wanted to help fight climate change. “That’s reassuring,” I said, my voice approaching normal talking level.

The man in the seat in front of me — an American, who looked like political pundit Steve Schmidt — swung his head around. “Could you keep it down?” he demanded, thereby ending our 3-minute conversation.

I wrote a note to my neighbor. “Was I being loud?” I asked. She shrugged and rolled her eyes toward the man sitting in front of us. When she got off at the next stop, we mouthed our adieus.

Towards the end of our journey, I met Meg in the snack car for lunch. “I got in trouble — for talking,” I told her.

“Me, too,” she said. “We were having a serious discussion about politics, but after a couple of hours, the man across the aisle asked us to be quiet.”

“I got shut down after a couple of minutes,” I said. “Guess you’re not supposed to talk on trains anymore.”

“He said you’re only allowed to whisper,” said Meg.

After lunch, we returned to our separate cars, and our journey continued noise-free and devoid of arrests or any commotion as we glided past vineyards and fields.

On the upside, the ride on the Whisper Train was smooth and on time, and — unlike Amtrak trains — the windows were sparkling, the seats were clean, and even the restrooms remained immaculate throughout the whole 7-hour journey.

Nevertheless, the Whisper Train trip was entirely soulless, leaving us with nary a story to tell or name to add to our address books once we disembarked in Paris at Gare de Lyon.

________________________________________

This is an excerpt from my memoir Gypsy with a Laptop.

In the past, before the era of mobile phones, people on trains used to read newspapers, printed books and magazines, smoke while enjoying coffee, drink alcohol, and socialize freely. However, nowadays, with noise-canceling headphones and ear pods, people act like they are isolated from the world, staring at their mobile screens. Even I still wear a facemask if I have to share the same space without proper ventilation. It seems like we are living in a new world, where technology has changed the way we interact with each other.