In today’s confusing world brimming with revisionist history, there’s only one thing I regard as stone-cold fact:

“In the beginning was the wrod.”

Because the word wasn’t born alone: it popped out with an evil twin — the accursed, lamentable typo.

The original writer who dutifully scratched the first symbols into a clay tablet surely inserted an error or five. Lord knows how many littered the first full sentence, which (I am not making this up) was an inscription carved into a fine-tooth comb: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.”

I imagine on the first take it read: “May this musk boot out the lick of the chair and the bear,” which would have been very confusing directions for a delousing utensil, forcing the inscriber to tear out his lice-ridden hair in frustration and go back to the chisel.

Even if typos are hard for modern scholars to spot in cuneiform, hieroglyphics, and Phoenician, just trust me — they’re there.

I know this because I’ve been studying typos for quite some time now — since around the time I scrawled “To Anut Angie” on a crayon drawing, a mistake my anut didn’t forget, but which did seem prophetic when she later went loopy.

My propensity for inverting letters, inserting “sound-alike” words, dropping s’s where they belong and adding them where they don’t, plagued me through the thick-pencil, cursive, and typewriter eras, and it still haunts me, even though for many years I’ve been writing on computers, discovering along the way that “White-Out” doesn’t work so well when dabbed on a screen.

Trivia item: What does liquid typo corrector have to do with “Last Train to Clarksville”? Bette Nesmith Graham in 1956 invented the former in her kitchen blender, calling it "Mistake Out." Fourteen years earlier, she’d given birth to guitarist Michael Nesmith of the Monkees. Hopefully she didn’t feel the same about him.

Having published many thousands of articles, I don’t think one has ever come out typo-free. On the very rare occasion I’ve ever turned in copy devoid of typographical errors, editors have felt compelled to insert their own. If somehow an article has made it through those hoops sans typos, the production staff puts them in for me, and proofreaders don’t weed them. A Portland editor once told me that my articles had the rare distinction of containing the worst typographical errors in the entire 30-year history of his newspaper.

I sometimes wonder if this is due to some karmic debt — if perhaps I was a typesetter in a past life inserting mistakes into the books of esteemed writers, and that now I must know their pain. But whatever the root cause, I unhappily wear the crown of “typo queen.”

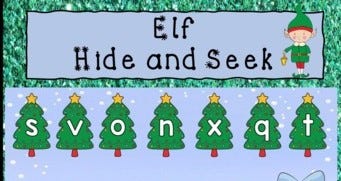

And, as reigning queen of the typo, I’ve developed a theory: the little rascals, which I suspect flew out when Pandora opened her box, are in fact living creatures — ornery elves hiding in the forests of letters. They camouflage themselves and silently hunker down in the text — and, magically, they only reveal themselves the second that you hit “Send” and the final copy goes zipping off.

And just when you’re throwing confetti celebrating that you’ve finished some massive project, the tittering typos jump out and yell, “Surprise!” and you find them all over the place and feel really stupid.

While I may be the world’s most prolific “typo-ist,” I am not alone. Scott Fitzgerald produced so many that upon reading an error-ridden edition of This Side of Paradise, literary critic Edmund Wilson declared that it was “one of the most illiterate books of any merit ever published.”

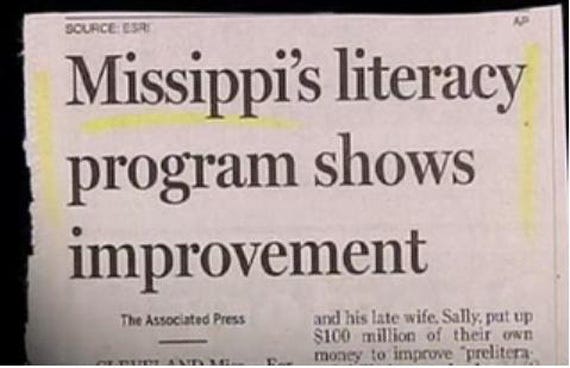

History has recorded many doozies.

For instance, Popeye the Sailor Man would instead have been downing cans of lentils, not spinach, had not a German chemist in 1870 made a typo with his decimal point, erroneously writing that one cup of the leafy green vegetable contained 35 grams of iron when the actual number was 3.5.

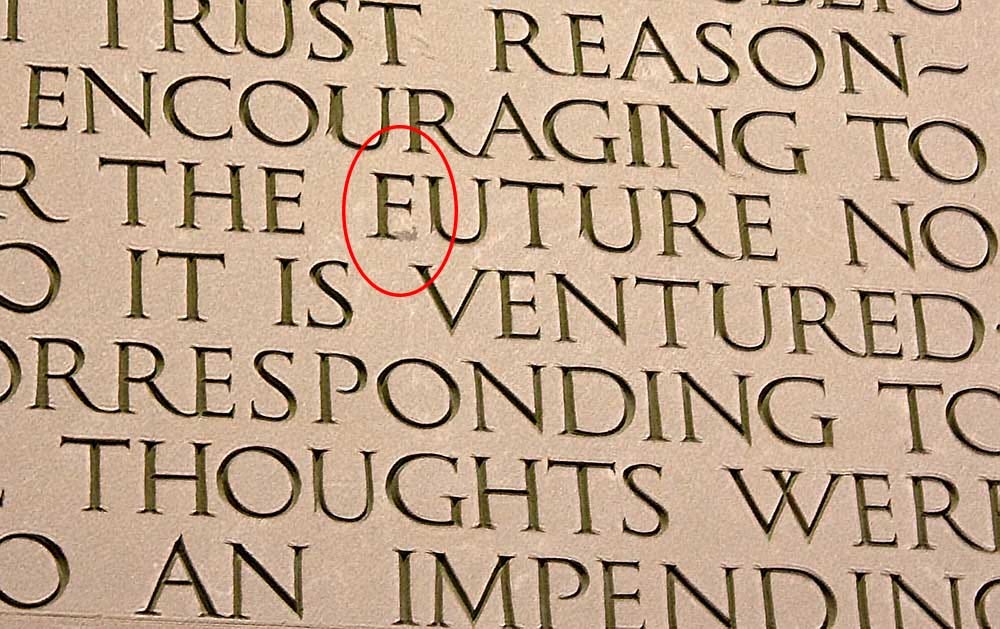

A typo caused the aborting of NASA’s 1962 Mariner 1 mission to Venus — a failure that came with a price tag of $80 million. And in 2010, a typographical error cost the director of Chile’s minting department his job, when he approved the production of millions of coins that had the country’s name spelled wrong. Even the engravers of the Lincoln Memorial chipped out an error in stone.

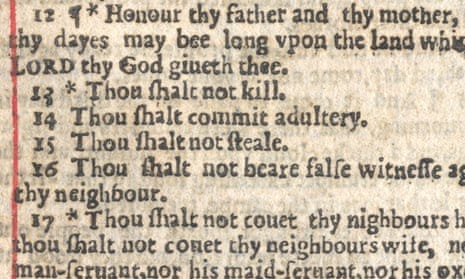

The situation grows particularly thorny when the little elves hunker down in The Good Book. In 1631, when Robert Barker and Martin Lucas printed a Bible that included a version of the Ten Commandments that accidentally encouraged extramarital hanky-panky, they were stripped of their printing license and fined what today would be a gazillion dollars or so, an amount that caused one of them to spend the rest of his life in debtor’s prison.

There are dozens of other examples of typos bearing false witness in the Bible such as “Go and sin on more” as well as advice to men to bear sons from their “lions” along with counsel to wives to “submit yourselves to your owl husbands,” which sounds sorta kinky.

Yet for all the horrifying scriptural recommendations that typos have offered, forcing thousands of sin-filled Bibles to be burned, I often wonder if there isn’t an undiscovered typo lurking in the shortest line of the Holy Writ.

To wit: “Jesus wept.”

While the plight of humanity is certainly worthy of shedding many tears, all the more since after millennia we’re still contending with heartbreaking wars, bedbugs, and lice, I prefer to think of Jesus as a pragmatic sort, who would have heeded the advice of my mother: “If you’re upset about something, just start cleaning!”

Thus, I must wonder if that two-word sentence “Jesus wept” should actually be “Jesus swept” making it a biblical illustration of the benefits of housekeeping to clear one’s head.

The reason I am rambling on about these grievous word errors is that despite multiple re-readings before I hit “Send,” I keep finding those cute li’l typo elves mucking about in my copy. Last week, for example, an alert reader notified me that I’d listed the lifetime of Karen Blixen as 1885 to 1862.

While I do think Blixen was witchy, I’m not sure that she was capable of dying before she’d been born, though if anyone could pull off such a feat, it certainly would have been her.

Nevertheless, instead of reading directly from my emailed “Rossi Reports” newsletter, I recommend that anyone wanting a smoother, relatively typo-free reading experience instead click on the post’s title, which will direct you to the webpage, where typos can be easily remedied.

In the meantime, I’ve been toying with the latest version of my epitaph: Here lies Melissa, who was fond of books, travel, and wine, and who adored her witty friends and kind Substack subscribers. However, she loved nothing more than working with wrods.

Melissa Rossi made approximately 16,000 typos while writing this essay.

This coming weekend will be the second memorial service for my friend, Bill Bradbury, former-Oregon Secretary of State. One of his duty's would have been to oversee the staff who wrote and failed to catch the following typo in the printed ballot mailed to millions; "There will be no pubic funds associated with this measure."

He laughed and laughed when it was pointed out.

This is hysterical. You know, the latest of Apple is to click the space bar and supposedly the word you want to write appears with no typo... Unless the context went wrong.