What If They Gave A War and No Missiles Came?

US conventional missile stocks are running low, while the Trump administration threatens possible military action all over the planet.

What are the two most frightening kinds of missiles? 1) The ones barreling towards you and 2) the ones no longer found in your arsenal.

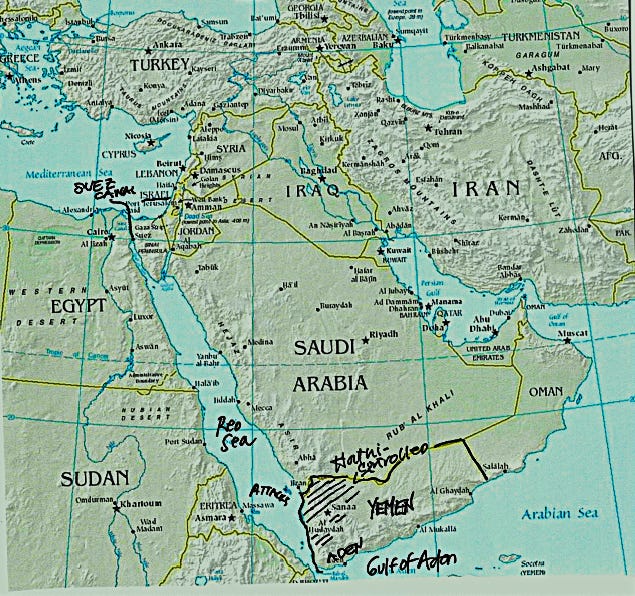

While I was researching the Houthis — now a household name thanks to the recent Signal scandal that accidentally looped in the executive editor of The Atlantic in official discussions about imminent attacks on the Yemeni militants — I stumbled upon a disconcerting fact: the American supply of conventional missiles, particularly ship-launched interceptor missiles, is dropping alarmingly low.

The world’s largest arms exporter, the US in the past few years has supplied 42% of the arms sold recently to 100 countries — and the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East have only boosted demand, while grants and sales to those two countries have helped to drain stockpiles, especially of air-defense missiles.

What’s more, the Houthi attacks on vessels entering and leaving the Suez Canal via the Red Sea has burned through more munitions — with over 800 missiles launched at Yemen and/or at Houthi drones by August 2024 — and that doesn’t include the strikes that continued through the year with a final concentrated effort in December.

According to Axios, the US had already spent $1 billion in munitions fighting the Houthi and their cheap drones by June 2024. According to Politico, the missiles used up by August included “135 Tomahawk land attack missiles that cost as much as $2 million apiece, along with 155 standard missiles from U.S. warships, which cost between $2 million and $4 million per missile.”

And now the Trump Administration is doubling down and vowing to stop the Houthi attacks on vessels traversing the Red Sea for once and for all — to free up the Suez trade route, to succeed where the Biden administration did not, to send a warning to the ayatollah in Tehran, and, I argue, to clear the way for a showdown with Iran. Which means hundreds more US missiles have been fired since March 15th.

It’s a worrisome state of affairs. “We know that the defense industry isn’t keeping up with the rate of expenditure either by the U.S. military or to support its allies and partners like Ukraine and Israel,” Dana Stroul, the top Middle East official for the Pentagon during the Biden administration, recently told Politico.

Part of the issue is the number of US defense contractors dropped from 51 at the height of the Cold War to a meager five arms makers today, according to a Congressional Research Service report last fall — and not only are missiles very pricy, arms makers aren’t exactly cranking them out. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, the company resulting from the 2020 merger of Raytheon and United Technology — RTX — produces only a few hundred Standard (interceptor) Missiles each year, and those are divvied up between the US and over a dozen allies.

Over recent months, think tanks, consultants, and US military commanders have warned that the arsenals of conventional missiles are dipping seriously low.

In October 2024, US Admiral Samuel Paparo, who heads the US-Pacific naval command, was asked whether ongoing fighting in Ukraine and the Middle East is affecting U.S. military preparedness in his part of the world. “Up to this year, where most of the employment of weapons were really artillery pieces and short-range weapons, I had said not at all,” Paparo said. “But now, with some of the Patriots that have been employed, some of the air-to-air missiles that have been employed, it is now eating into [our] stocks. … and to say otherwise would be dishonest.”

As the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) noted in a 2023 report, “The U.S. defense industrial base is not adequately prepared for the competitive security environment that now exists. It is currently operating at a tempo better suited to a peacetime environment. In a major regional conflict—such as a war with China in the Taiwan Strait— the U.S. use of munitions would likely exceed the current stockpiles of the U.S. Department of Defense, leading to a problem of “empty bins.”

This leads me to wonder about several things:

First, would the US (linking arms with Israel) have enough missiles for an effective attack on Iran? Let’s assume that a) Iran’s military is no match for the US (especially with ally Israel); b) that an attack to take out Iran’s nuclear production facilities doesn’t lead to a months-long protracted war; and c) that Iran didn’t/doesn’t yet have nuclear capabilities — and say, “Yes, it’s do-able.”

Second and more important, however, is the question of if the US could win a sustained war against China — triggered perhaps by a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. That’s way trickier.

In January 2023 — before the Israel-Hamas war and the US attacks on the Houthis further drained the US arsenal — the Center for Strategic and International Studies simulated a U.S.-China conflict, concluding that the U.S. military would use up all of its long-range anti-ship missiles in the initial days of the conflict, while joint air-to-surface standoff missiles would hold up for three or four weeks.

The Heritage Foundation, which appears to be highly influential with the Trump administration, has called the state of the stockpile a critical “missile gap”— defined as “the broad distance between the munitions the U.S. currently has and the amount we’d need to defeat China in a conflict. This gap is exacerbated by our now-limited defense industrial base and the long lead-times involved in producing more munitions.”

Third, if there’s a shortage of conventional missiles, does that increase the odds that the US might use nuclear weapons — of which we have plenty — to get the job done? Hmmm. Dunno, but an unnerving thought.

Fourth, does the US need to revamp the way it fights wars — especially against militants like the Houthis? While the Houthis attacking US warships (and commercial vessels) with drones that cost $2,000, the US shoots them down with missiles carrying a $2 million price tag. It might not be the wisest tactic.

Elon Musk controversially has suggested ditching fighter jets, such as the problem-plagued F-35, with swarms of AI-controlled drones.

It’s not like missiles will all be spent tomorrow, but it will take a few years just to get the stockpiles back to normal — and that’s assuming there’s not a major war with China or anybody else.

Teddy Roosevelt often advised “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” What’s happening lately in the US is turning that on its head, striking me as “Threaten really loudly and carry a whittled-down twig.”