Who steamrolled the Impressionists?

As France celebrates 150 years of Impressionism, it's fitting to ask why these artists were rejected for decades. The great Paris patroness of the arts, Mathilde Bonaparte, was key.

Starting this month across France, museums are celebrating the 150th anniversary of the birth of Impressionism, or more precisely the year that Impressionists took their name. The highlight of these shows is “Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism,” which runs from March 26th to July 14th at the Musee D’Orsay in Paris — and in September the exhibition will come to The National Gallery of Art in DC.

Thanks to the patronage of Meg Tufano, I will be reviewing that show — and its hour-long virtual reality immersion — in a post later this month.

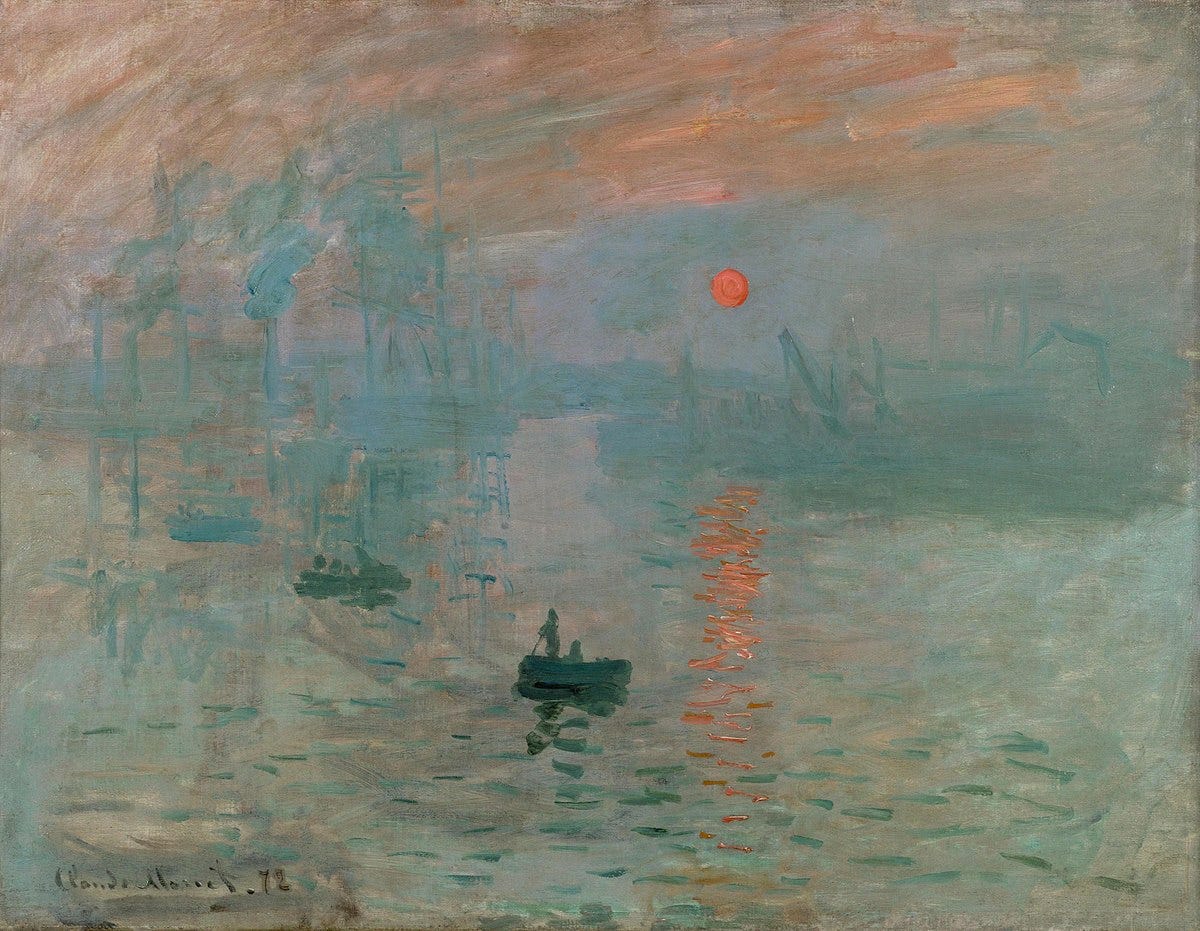

Before delving into that exhibition, however, it’s elucidating to ask why these outsider artists — which included Monet, Renoir, Cezanne, Sisley, Degas, Morisot, and Manet — were cast aside for decades.

Granted, they embraced radical themes — ignoring the Greco-Roman classicism of mythological heroes and battles that were the standards of the era to instead focus on light-infused portrayals of nature and commoners in everyday settings — and their techniques of thickly-textured strokes and even their frequent practice of painting under the sun in plein air threatened the status quo of the day.

But there’s an even bigger reason that these French artists’ works were typically rejected from the Paris Salon — the 19th-century’s most important art exhibition in the world as well as the only game in town for Parisian artists.

And that reason is Mathilde Bonaparte, niece of Napoleon I, and the most powerful person in the art world during the mid-1800s. Mathilde’s mightiness stemmed from her deep attachment to her cousin, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, to whom she was once engaged — until her father, Jerome, annulled the engagement in 1836 after Louis-Napoleon’s first attempt at unseating the French king.

Mathilde: Rule-breaking Patroness of the Arts

Even before Louis-Napoleon was elected as France’s first president in 1848 — going on to declare himself emperor in 1852 and reign for 18 years — his cousin Mathilde was a well-known figure in Paris society, living scandalously.

In 1840, Mathilde married the wealthy Russian Anatoly Demidov, one of Europe’s richest men and a renowned art collector, living with him in St. Petersburg and Florence. She soon became disenchanted with his extramarital affairs and abusive treatment — and after he slapped her at a ball, she walked out on him, snatching back her dowry diamonds when she left.

Demidov claimed the jewels were his, but Tsar Nicholas I sided with Mathilde, who was his second cousin — and a Russian tribunal ruled that Demidov had to pay Mathilde 200,000 francs annually — around $40,000 a year, a vast sum back then, making Mathilde rich for life.

Until they became well-paid government officials during the Second French Empire (1852-70), simply because of their last name, Mathilde’s father Jerome and her brother Plon-Plon were always after her money, the source of many familial squabbles. At one point, she stopped speaking with them.

After leaving Demidov, still-married Mathilde fled to Paris in 1846, and blatantly defying social norms, she moved into a mansion with the also-married Count Émilien de Nieuwerkerke, a Dutch noble. Tongues wagged.

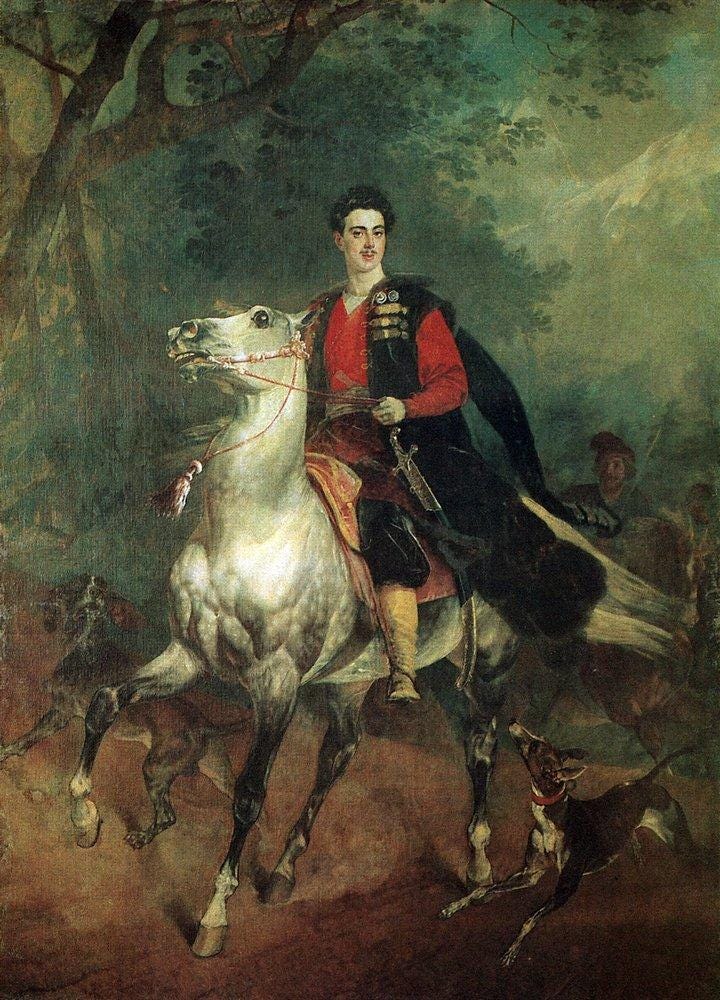

Handsome, arrogant, and imposing in stature and personality, Nieuwerkerke was nothing more than a failed sculptor until he latched his life onto Mathilde’s rising star.

Fortuitously for both, in 1848, Louis-Napoleon — an escaped convict who’d been living in London — came to power as president of France. As the new French leader was not married, and his beloved courtesan Harriet Howard didn’t fit the bill, he tapped his former fianceé Mathilde to serve as his first lady at official events. In that role, she not only hobnobbed with heads of state and visiting VIPs, Mathilde also oversaw his soirees and cultural affairs.

What’s more, even though Nieuwerkerke didn’t have the credentials, Mathilde pressured her cousin to hire her live-in lover as director of the French national museums, including the Louvre. When Louis-Napoleon became Emperor Napoleon III in 1852 — through a coup that was partially funded by Mathilde — her cousin bought Mathilde a splendid mansion. And Nieuwerkerke’s title changed to director of imperial museums.

Mathilde’s Continuing Rise in the World of the Arts

After being crowned emperor in December 1852 and taking the title Napoleon III, her cousin needed a wife — and even though Mathilde begged him to not marry Eugenie de Montijo, he wed the Spanish countess the next month.

Nevertheless, Mathilde continued acting like a First Lady, hosting high-profile literary salons and inviting visiting VIPs, intellectuals, and creative sorts, in between throwing intimate dinner parties attended by the likes of Louis Pasteur, Gustave Flaubert, Alexandre Dumas fils, and Theophile Gautier, the leading art critic of Paris. Her salons, filled with heads of state and visiting princes, were such “to-dos” that they easily showed up the salons of Empress Eugenie, who often clucked to the emperor about Mathilde, not approving of how she was living in sin.

More detrimentally for outsider artists, Nieuwerkerke’s power was growing. As superintendent of imperial museums, Nieuwerkerke not only selected artwork: he oversaw the Paris Salon, the make-or-break event for artists, which made him the most formidable figure in the entire French art world. And Mathilde was very much in his ear.

Nieuwerkerke was caricatured as Mathilde’s poodle in this drawing La Ménagerie impériale by Paul Hadol, 1870.© Fondation Napoléon

Mathilde and Nieuwekerke: the Steamrollers

For artists, exhibiting at the Paris Salon, then an annual event, brought exposure before millions of viewers; if awarded a medal, a lucrative career was guaranteed. If rejected from the salon — or worse, poorly reviewed there — artists suffered, in some cases, having to repay those who had previously commissioned their work.

And, Nieuwerkerke’s tastes, like Mathilde’s, were conservative.

"Mathilde did not have an official position, but she was very influential in the art world — with the artists and the writers too, and, of course, her boyfriend Nieuwerkerke," Annick LeMarrec, archivist at Corsica’s Musee Fesch, which recently held a show of Mathilde’s paintings, told me. "But Mathilde was very conservative in her artistic tastes. She supported academic, classical art. She hated Monet, Manet, Courbet, and the other modern artists."

It was said that Mathilde was the key person in all Nieuwerkerke’s artistic calls, including who won awards. The power duo favored historical works and portraits of heroes, including Napoleon I, and were certainly not supporters of new movements springing up, be they the flicked paint capturing nature en plein air favored by the likes of Monet and Pissarro, or the new realism pushed by Courbet, which captured the lives of peasants and streetwalkers.

Paintings of Men Who Don’t Change Their Boxers

Upon seeing Jean-François Millet’s Man with a Hoe, a painting of a farmer in a field, Nieuwerkerke attacked it as “the painting of democrats” — a high insult in his book — that exalted “men who don’t change their underwear.”

The most influential art critics of the day — most dear friends of Mathilde, who often dined with the princess and Nieuwerkerke — typically mirrored their opinions, and few dared to openly defy them, underscoring the power Mathilde exerted over the art world.

Whether as a result of Mathilde’s whispering in his ear or simply his inflated ego, Nieuwerkerke also pushed through reforms that further hurt artists, particularly those who were unknown. In 1853, he changed the Paris Salon from a yearly event to a bi-annual exhibition; he claimed the move was to give painters more time to produce works of quality, but the reality was it meant less work for him. And he also changed the jury that selected the painting from artists to the elite government-appointed members of Academie of Beaux-Arts, who were more likely to be academics and nobles than painters themselves.

Artists like Manet, Monet, and Pissarro saw their works rejected nearly every year in the first decade that Nieuwerkerke was in power, although in what smacks of nepotism, the works of Mathilde — an accomplished watercolorist — were several times displayed — as were those of Nieuwerkerke himself.

Nieuwerkerke’s tastes and changes were already provoking backlash from outsider artists, who took to loudly protesting under his office windows at the Louvre, when his status soared further: in 1863 he was also appointed superintendent of the École of Beaux Arts, which gave him even more room to impose his prosaic tastes on the leading art school in France.

Previously, artists had been able to submit as many works as they wished to the jury; that year, announced Nieuwerkerke, they could submit only three. This rankled even established artists such as Ernest Meissonier, who frequently exhibited in the Paris Salon — some years as many as six of his works were selected by jury for display: now he could only exhibit a trio every two years.

The Painters Strike Back

Along with Ernest Meissonier and Eugene Delacroix, hundreds of artists signed a petition, presented to the Nieuwerkerke’s boss, the Minister of State, by Edouard Manet and Gustave Doré, protesting the change. Nieuwerkerke dismissed their concerns and proceeded with his plans, which led Meissonier and others to boycott the 1863 Salon.

That year, Nieuwerkerke’s academic, traditionalist standards were even more vigorously enforced when he urged the jury to be even more selective: of the more than 5,000 paintings submitted that year, a mere 2,000 were accepted.

The news that 60 percent of the pieces had been rejected was met with fury, and newspapers prominently featured the fiery public debate. So many complained that — to the chagrin of Mathilde and Nieuwerkerke — the emperor felt compelled to hold another exhibition, the Salon des Refusés, or the Exhibition of Rejects. where the works of Manet, Pissarro, and Whistler were among those shown.

Even though Nieuwerkerke tried to strangle publicity of the event, thousands showed up to take in the works of the rejects, and despite being ridiculed by most art critics, it help to solidify the movements of these outsider artists.

Reactions to the Outsiders

Given the scandal surrounding the 1863 Salon, Nieuwerkerke was forced to walk back his previous changes: the Paris Salon, he soon announced, would return to being an annual exhibition. And in the 1864 Salon, artists were again part of the jury, which was instructed to be more open-minded: that year only a third of the art works submitted were rejected. Two works of Manet were exhibited in the 1864 Salon, although they did not receive critical acclaim.

Mathilde’s friend, the critic Gautier, was particularly scornful of Manet, characterizing his work, Incident at the Bull Ring, which was shown that year as “completely unintelligible.”

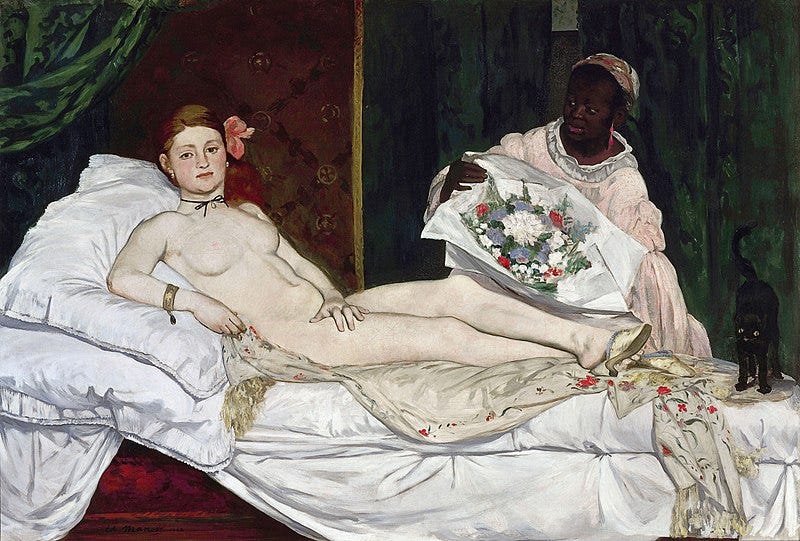

In the 1865 Salon, Manet exhibited Olympia, a realistic nude seen as so shocking that not only did it provoke the Empress Eugenie to smack it with her fan, it required guards to keep the masses from attacking it, until finally it was rehung much higher.

While Zola regarded it as “a masterpiece,” Gautier described the painting of a woman in bed as “a puny model stretched out on a sheet."

Monet also was accepted into the 1865 Paris Salon with two well-reviewed seascapes, though in the more conservative Salon of 1867, Monet’s works were rejected. He was so dejected that shortly thereafter he tried to commit suicide by jumping into the Seine.

Outsider artists demanded that the government stage more officially recognized “Shows of the Rejects,” but Nieuwerkerke managed to stifle their demands for more outsider exhibits during his tenure. They wouldn’t hold another one until 1874.

Throughout it all, Mathilde, Nieuwerkerke, and Gautier, who became Mathilde’s personal librarian in 1868, remained critics of the style that in 1874 would be dubbed Impressionism.

She Made Her Friends Rich

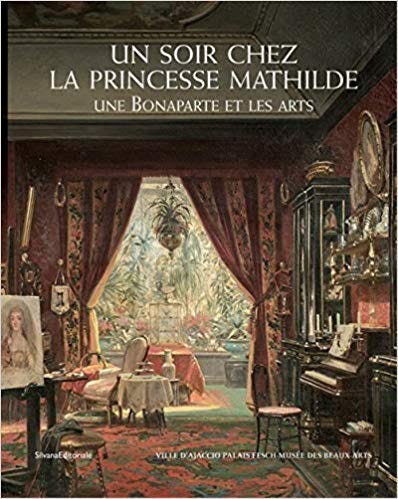

Although Mathilde’s influence was detrimental to many outsider artists, she was a generous patron of the arts to others. She bankrolled the production of a controversial play of the Goncourt Brothers — Henriette Maréchal — and widely instilled a trend of home decoration and beautification. A fan of Eugene Giraud, her painting teacher, and his brother Charles, she helped to popularize paintings of the interiors of Parisian notables, including of her own home, and she ensured that her cousin’s government bought many of their works.

With her soirees and salons often captured in the writings of that era’s diarists and journalists, including Horace de Viel-Castel and the Goncourt Brothers, Mathilde, they record, was growing more anxious and less enamored of Nieuwerkerke, who was playing around on the side. In 1869, she finally kicked him out — and soon began a romance with another artist, Claudius Popelin.

End of an Era

Without Mathilde’s backing, Nieuwerkerke’s days were already numbered, but in 1870, the Second French Empire came crashing down, after Napoleon III declared war on Prussia, losing the war in mere weeks. The mightiest man in French art lost his post, and Mathilde’s important role within the government likewise evaporated with the emperor’s September 1870 surrender.

Nevertheless, after a brief stay in Belgium, Mathilde returned to France. In the years that followed, Mathilde — who married Popelin in 1873 — continued her Paris dinner parties and salons, the seat of critic Theophile Gautier now often filled by his same-named son. In her later years, she befriended Marcel Proust, then a fledgling author.

Proust who was so intrigued by the last remaining Bonaparte of note — Louis-Napoleon had died in 1873 — that he implored Mathilde to write her memoirs, offering to serve as her secretary in the endeavor. Alas, she declined the offer.

By 1881, Manet had become immensely popular, and the next year he was awarded the Star of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Shortly thereafter, he received a congratulatory note from Nieuwerkerke, now living in Italy. Manet responded via a mutual friend: "Tell him I appreciate his good wishes, but that he could have been the one to decorate me. He would have made my fortune and now it's too late to compensate for twenty lost years."

Manet died several months later of syphilis.

In January 1904, Princess Mathilde passed away in Paris, her five decades of salons and soirees finally ended. At the news, the younger Theophile Gautier commented, “The death of the princess means more than an ordinary occasion for mourning; it is an historical event. Amid all the beautiful and noble things that are passing away shattered by time or by the hands and the evil passions of men, we may say that the disappearance of Mathilde’s salon tolls the knell for the end of a world.”

But the outsider artists that Mathilde and Nieuwerkerke blocked from acceptance got the last laugh.

The writers of Soir Chez La Princesse Mathilde Bonaparte, published in 2019, characterize her as “a Gertrude Stein who arrived too soon, a whimsical Peggy Guggenheim in the wrong era.” But, in looking back at her legacy, they ask “Should we blame her for not having known how to see Delacroix or Courbet, Manet or the Impressionists?”

For me, the answer is yes.

In the end, Mathilde’s rigidness hurt her estate nearly as much as it hurt outsider artists. When her collection, which had been so highly regarded during her lifetime, was sold after she died, it fetched little. As the authors of Soir Chez La Princess Mathilde note, “Her collection focused on the ultimate refinements of classicism, while the romantic became universally famous during her lifetime. When sold at auction, her collection of masterpieces disappointed everyone. The artists that Mathilde had loved during the Second French Empire had passed out of fashion at the beginning of the 20th century."

And Mathilde, the grand patroness of French art, may now be best remembered not for what she collected, but the masterpieces that she passed over.

A similar version of this post appears on the M.S. Rau website.

Proust was in his early twenties when he offered himself as Mathilde's biographer and wasn't as popular as one might think. This was mostly because of his mother, who was a wealthy Jewish heiress of Germanic ancestry. As a result, many people including Mathilde considered him an outsider and refused to accept him. Nevertheless, this rejection fueled his ambition to be accepted at any cost. At that time, French society was openly anti-Semitic. Years later, in 1894, the Dreyfus Affair created a divide in high society, and things only got worse from there.