A Dizzying Trip with the Impressionists

Musee D'Orsay's experiment with virtual reality was a nightmare for me.

Rehearsal of Ballet by Edgar Degas — one of the masterpieces on show at the Musee D’Orsay that we didn’t see.

I find world-class art museums to be daunting affairs. Drinking in room after room of art sometimes overwhelms me, but the experience I had with Meg Tufano last week in Paris blasted “Stendhal Syndrome” to whole new heights.

Five days later, I haven’t yet fully recovered from what happened at Musee D’Orsay.

“Stendhal Syndrome,” named after the experience of writer Stendhal during his 1817 museum-packed visit to Florence, is characterized by dizziness, heart palpitations, feeling faint, and general disorientation after being exposed to beautiful art. It’s not officially recognized as a syndrome, but hospitals in Florence have long documented this reaction among visitors to the Uffizi Gallery, which holds Renaissance works by the greats, including Botticelli, Da Vinci, and Michelangelo.

One of the paintings we took in at the D’Orsay after the virtual reality show, though I don’t remember seeing it at all. Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets by Édoard Manet. Even though I don’t recall taking the photo, it captures how everything looked to me post-VR: blurry and askew.

Spreading along the Left bank of the Seine in what was previously a Belle Epoque train station, the spectacular Musee D’Orsay, with its high, vaulted glass ceilings, is the size of two football fields on each of its five floors and it holds the world’s largest collection of works by Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.

The second-biggest art museum in Paris is fast gaining a reputation for its ambitious embrace of new technologies from AI to virtual reality, a trend gaining favor in the last few years, including at the Louvre, which recently ran a virtual reality experience of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

Last fall the D’Orsay’s Vincent Van Gogh exhibition offered museum-goers the chance to “talk” with an AI-generated avatar of Van Gogh, who explained his 1890 suicide saying, “In my darkest moments, I believed that ending my life was the only escape from the torment that plagued my mind.”

The exhibit also featured a 20-minute virtual reality immersion experience called “Van Gogh’s Palette” about the painter’s last months in the French village Auvers-sud-Oise.

Even though its high-tech bells and whistles were mocked by some, the 4-month Van Gogh exhibit was a huge hit, bringing in 7100 visitors per day — and breaking all records. “The show’s A.I. and immersive V.R. experiences were largely ridiculed in the press, but they proved persuasive to new audiences,” noted Artnet.

The museum is now trying an even bolder experiment with it latest exhibition, Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism, which celebrates the 150th anniversary of when Impressionism got a name. Opening on March 26, this show also includes a virtual reality experience, called “Tonight with the Impressionists.” which was originally billed as lasting a full hour, although when Meg Tufano and I arrived for the second day of the exhibit, the VR immersion had been whittled down to 45 minutes, which in my opinion is about 45 minutes too long.

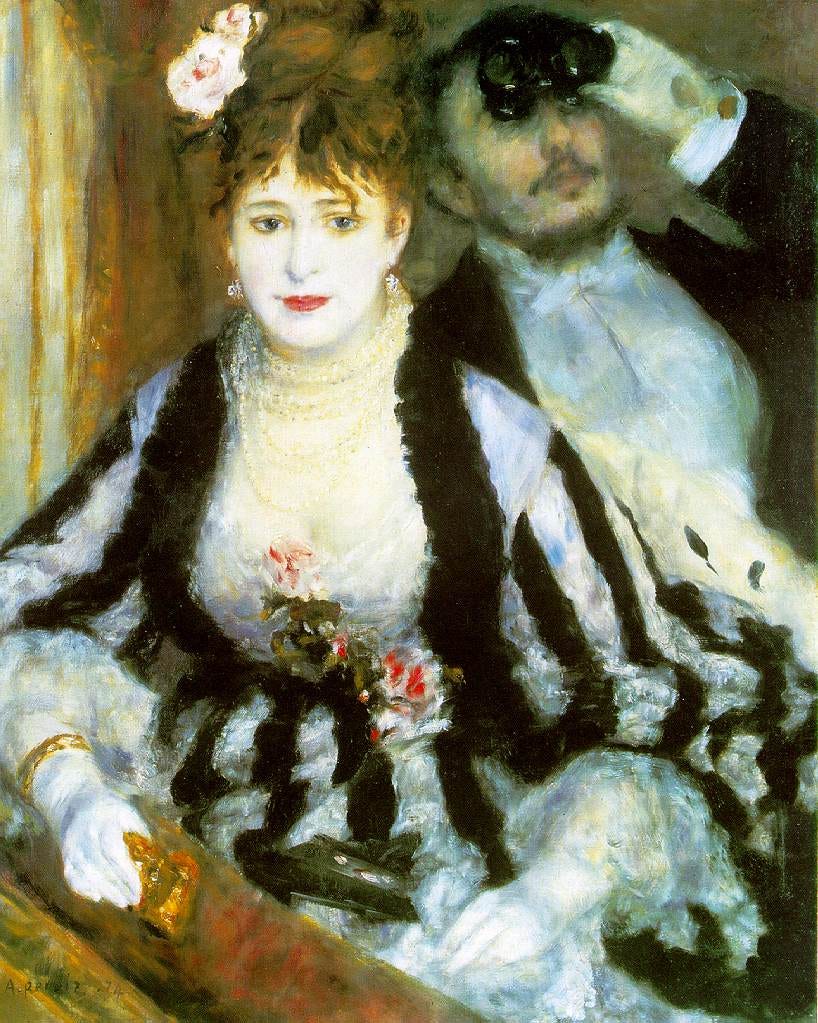

La Loge by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1874, another dazzling work displayed at the “Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism” exhibition that we amazingly missed.

Meg and I tried to first enter the gallery showing the actual paintings, which included such masterpieces as Claude Monet’s Boulevard des Capuchines, Degas’ Ballet Rehearsal, and Berthe Morisot’s Hide and Seek, among dozens of others. However, seeing our tickets, they told us that we had to do the virtual reality experience first, before taking in the exhibit — and we were directed to the adjacent gallery, where we waited with a couple dozen people, almost all ranging in age from 40 to 80 years old, for our VR immersion.

Once the VR goggles were fitted to our heads — thus blinding us to all but the virtual reality show — we set off. Other partakers appeared as shimmery ghost outlines as we walked along with our VR guide “Rose.”

The visuals opened with Rose, clad in a 19th-century dress, telling us about the just-opened opera house and “guiding” us back in time past horse carriages to the studio where the “Show of the Rejects,” was about to open on April 15, 1874. We “walked” through the gallery, where assorted artists, including Monet, Degas, and Cezanne, discussed their exhibit opening that night.

While the virtual reality show was beautifully rendered, I was immediately thrown off by several things: the virtual people were short — the height of 8-year-olds — and their comments to each other alluded to things that weren’t at all explained, including a rivalry between Manet and Cezanne as well as how Renoir exhibited in the state-run Paris Salon under a fake name.

What’s more, about three minutes into it, I was hit with a headache, which only grew more intense, and I was unable to take notes because of the goggles, not to mention that at least thirty people bumped into me. (Meg later said I was often outside the lines, but to me I appeared to be in the so-called blue zone that travels along with you, showing you where to stand.)

Worse: the special effects. When the miniature Paul Cezanne talked to us, for example, he wanted to tell us about his work called The Modern Olympia, which was his reinterpretation of Manet’s controversial 1863 painting Olympia, requiring that we virtually zip up at the speed of light to some virtual room via an invisible elevator, an experience I didn’t relish.

More frightening: when Rose wanted to show us the painters outside working in plein air, and we had to follow her along a narrow plank over a stream — with Rose falling in. Even though I rationally knew I was not traversing a plank in real life — I was only walking on a flat floor with no stream running underneath — it was difficult for me to get my feet to virtually cross the thin board.

And that’s when vertigo set in, only exacerbated by more virtual climbs up precarious steps and more invisible elevators.

30 minutes into the VR immersion, my head was throbbing, my heart was pounding, my back felt painfully stiff, my feet hurt, and I felt like I was spinning.

“I’M DONE!” I loudly announced, ripping off the stupid goggles, and prompting a staff person to run over, ask if I was all right, and escort me to an orange couch in the decompression area, saying that she thought 45 minutes was too much. I got the impression that I wasn’t the first to have quit early. Meg appeared seconds later, also feeling dizzy and unable to complete the experience.

Thank God we stopped early because at the end of the immersion experience, a high-speed horse gallops right through you — which scared the bejeesus out of the VR partakers, to judge from reviews of it.

We had to sit there on the couch for a few minutes, and Meg finally suggested we go to the restaurant upstairs for a coffee. We must have appeared dazed because another staff member appeared to walk us to an elevator.

The café, with decorative bells hanging overhead, was beautiful — all the more with its oversized clock embedded in a window. Over coffee, Meg wondered why the experience had to include the thrills and spills, like the plank-crossing ordeal, which we agreed was gratuitous.

Furthermore, while the VR experience hinted at the artists’ disenchantment with the state-sponsored Paris art establishment, which rejected them, it didn’t provide the details and context I’d hoped for and that prompted us to delve into the disappointing VR exhibit in the first place.

Even after the coffee, I felt discombobulated, as though I’d just wobbled off a rollercoaster, and we wandered through rooms lined with paintings by Van Gogh, Manet, and Renoir, which I really couldn’t take in, because I just felt achy and wobbly. Looking through photos I snapped, I don’t recall anything — that’s how loopy I felt.

Another painting I don’t recall seeing.

So, both of us feeling nauseated, we left the grand and wonderful Musee D’Orsay — only later realizing we’d been so out of it that we forgot to return to the actual “Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism” exhibition, which was what we had first tried to enter and that displayed the actual masterpieces that had hung at the original “Salon of the Rejects” show 150 years ago.

That night heading for dinner at Georges, a fancy-schmancy restaurant with a view of the Eiffel Tour, we struggled even taking the four escalators up, having to stop after each one, feeling dizzy yet again. Though much improved, five days later I still feel light-headed.

We did feel validated, however, when the art critic for the New York Times, who raved about the actual exhibit of paintings, panned the VR immersion experience, saying it didn’t add much and that she also emerged from it dazed and confused.

So should you be heading to the Musee D’Orsay, take our advice and just drink in the lovely paintings, and skip the virtual reality goggles, unless you want to view art with that fresh-off-a-rollercoaster sensation of having your stomach wrapped around your neck.

Makes a lot of sense, indeed. Who would be willing to try such an experience for forty-five minutes? The rabbit hole is OK on paper but never wearing goggles. Apple has the new brand Vision Pro and it's heavy to wear on the head and over the nose, spatial software is still a joke and corners are too blurry. I'm trying to imagine how many times you would bump into things blindly. Nevertheless, it was an amazing read.