The Panama Canal: What's the deal?

As loads of hooey circulate about Panama, making it headline news, here's an easy-to-skim primer about the major shakers and events in the country the US helped to create.

“We’re taking it back!”

That’s what President Donald Trump said in his inaugural address — and keeps repeating. “We’re going to take it back, or something very powerful is going to happen,” Trump said last Sunday.

He was referring to the Panama Canal — the 51-mile waterway built by the United States and fully ceded to Panama in 1999. The passageway that is key to US maritime trade is being controlled by China, Trump keeps asserting —falsely.

It’s like chalk squeaking on the blackboard for Panamanians every time the US president makes the “China’s in control!” claim or threatens to wrest the canal from the country that is widely considered to have done a fine job of independently running it for 25 years.

Panama’s president José Raúl Mulino continually begs to differ with Trump on who’s operating the canal, repeatedly explaining that “every square meter” is in Panama’s hands.

The messages coming from DC also concern Panamanian Rich Cahill, who runs Panama Canal Fishing, taking tourists out on Galun Lake. “China has nothing to do with operating the canal, zero, absolutely nothing,” says Cahill, whose parents were US citizens. Almost every day, Cahill crosses the canal — and, contrary to the picture drawn by Trump, there are no Chinese troops to be seen. “We fought tooth and nail to get control of the canal. The last thing we want to do is give up the canal to anyone.”

Trump is exaggerating what may indeed be a legitimate concern: Hong Kong firm CK Hutchinson leases ports at both ends of the canal, which could cause a thorny situation in the event of war — since Hong Kong is now part of China. Also worrisome: China, now Panama’s main trading partner, is building a fourth bridge across the canal and has been angling to finance a dozen more infrastructure projects through its Road and Belt Initiative, a loan program funding major projects in over 100 countries.

The Chinese presence along the canal poses such an alarming security threat for Trump that he wouldn’t rule out military action to take back the canal, he told reporters. Of course, that probably wouldn’t be necessary — given that Panama hasn’t had a standing army or navy since the US invaded it in 1989 to oust CIA snitch turned Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega — a matter we’ll get to shortly.

Nevertheless, when Trump began his screaming, Mulino promptly initiated an audit into the two ports leased by Hutchison. Rumors in the Panamanian press are that something fishy may have been going on there with payments. According to the Rio Times of Brazil, “An ongoing audit of Hutchison’s concession could revoke the contract, opening bids to U.S. or European firms.”

Last weekend Secretary of State Marco Rubio jetted to Panama, the former senator’s first visit to a foreign country since taking the role. He delivered the message that “the United States cannot, and will not, allow the Chinese Communist Party to continue with its effective and growing control over the Panama Canal area.” Rubio added that it was “absurd” that American military vessels have to pay to use the canal, when the US is responsible for defending it in the case of attack or should its neutrality compromised.

In an apparent nod to DC, Panama’s president promptly announced that the country was dropping out of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Panama signed on with BRI in 2017, and was compelled to drop its recognition of Taiwan, the island that mainland China wants to grab.

But then the Trump administration pulled another rabbit out of the Panama hat, announcing on Wednesday that US military vessels could cross the canal free of charge!

However, that was followed up by a statement by the Panama Canal Authority, which is the agency overseeing tolls, saying that the State Department’s claim is a whole lot of horse puckey.

In his weekly press conference Mulino said the Trump administration, is putting out rafts of “lies and falsehoods” adding that the situation is growing “intolerable.” Meanwhile outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart kept trumpeting the State Department’s version, although Secretary of State Rubio himself finally walked it back, saying the US “expects” the tolls will be waived someday.

Another thing that’s surely grating on Mulino and other Panamanians: the country recently completed a major $5 billion renovation, putting in another lane, expanding width and depth, and doubling the canal’s capacity by making it possible for larger Panamax ships to get through. And the loans for that are carried solely by Panama. Matthew Tomlett, a Panama-based American who voted for Trump, likened the US threats to seize the new Panama Canal to the absurdity of the British prime minister now trying to take back the American colonies.

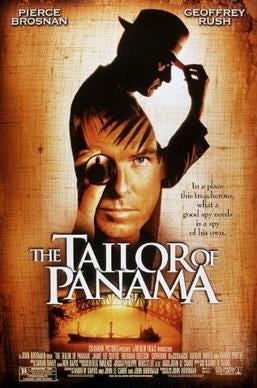

In the 2001 movie “The Tailor of Panama,” a dodgy British intelligence agent convinces the US government that Panama is selling the canal to China, prompting a US invasion.

Concern about Chinese activities in Panama is nothing new: In 1997, for example, US Coast Guard Captain G. Russell Evans published “Death Knell of the Panama Canal?” denouncing the Panamanian government for leasing the two ports to Hutchison, which he called “a Red Chinese ally.” A former adviser to the National Security Center, Evans hinted that Chinese donations to the 1996 reelection campaign of President Bill Clinton may have been the reason why the US government looked the other way at the time.

But there are a few other things that rarely make it into articles about Panama — from why the American attempt to build the canal succeeded when the French had failed to the reason President Jimmy Carter signed a 1977 ceding control to Panama, which conservatives and hawks have now been squawking about for nearly fifty years.

Nearly Déjà Vu

As noted in a previous post, the French attempt to build the canal during the 1880s nosedived due to ridiculous design, financing woes, and diseases — malaria and yellow fever — that killed some 22,000 workers.

Frenchman Philippe Bunau-Varilla sold the remains of the French project to the US, then financially backed revolutionaries to secede from Colombia and start Panama — an effort helped along by American gunboat diplomacy. The US promptly negotiated a canal treaty with Panama and began work in 1904.

The massive project quickly became nightmarish: the first chief engineer, John Findlay Wallace, was overwhelmed by the enormity of the task — all the more when an epidemic of deadly yellow fever descended. By 1905, laborers were fleeing Panama in swarms — and Wallace packed it up as well.

The Heroes of the Canal

Enter John Frank Stevens, a civil engineer who’d made a name for himself building the Great Northern Railway in the US, blasting tunnels through formidable mountains.

Stevens did two important things as chief engineer of the Panama Canal project: he realized it would require locks and dams. And he listened to Dr. William Crawford Gorgas. An army surgeon, Gorgas kept telling the Teddy Roosevelt administration that yellow fever and malaria weren’t caused by “bad air” — they were spread by mosquitos.

US officials initially maintained that the diseases wouldn’t affect “clean, healthy, moral” Americans like they had the French, who apparently had none of those qualities.

Gorgas and his team drained standing water, put up screens, and sprayed pesticides to kill off the deadly pest. It made all the difference. Although some 5,000 people died during the decade-long construction of the canal — some from injuries — the number was not even a quarter of the number of workers who perished during the French attempt.

Woes in the Canal Zone

The 1903 Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty, negotiated for Panama by Frenchman Bunau-Varilla who was indebted to the United States, gave the US the right to govern a 10-mile-wide strip along the 51-mile canal in perpetuity.

This 533-square-mile strip of known as the Canal Zone soon filled with some 45,000 Americans — most of them military personnel or otherwise employed by the 13 US military bases and facilities that shot up in the zone, or near it.

John McCain was born in the Zone, and Stephen Stills grew up there. Stills has said the local music influenced his own, as can be heard in his song “Panama.”

A Colony, Sorta

Many Panamanians were upset: the US effectively was running its own wealthy, isolated colony in the middle of their country. “Zonians” as those living in the Canal Zone were known, often didn’t see it that way. “It wasn’t colonialization in the traditional sense of the word,” says George, who grew up there. The Canal Zone brought jobs to Panamanians, he says, and helped to create the country’s middle class. Besides, he added, “Panama wouldn’t exist without the United States — it would still be a territory of Colombia.”

He’s referring to the Teddy Roosevelt’s gunboat diplomacy that supported the creation of the country in 1903. Implied in that protection was that Panama would allow the US to build a canal there.

However, the Americans, it may be argued, also appeared to influence elections and governments in Panama, where it wasn’t uncommon for presidents, who came from the wealthy elite, to last barely a year, sometimes only a week. In 1940, for example, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to expand US bases in Panama, President Arnulfo Arias did not support FDR’s plan, making noises about how the US would have to pay more.

What’s more, having previously served as Panama’s ambassador to Italy, Arias was widely believed to be pro-Mussolini and thus pro-Axis. Barely a year into his term, he was ousted by Panama’s National Guard, although many believed that Roosevelt was behind it.

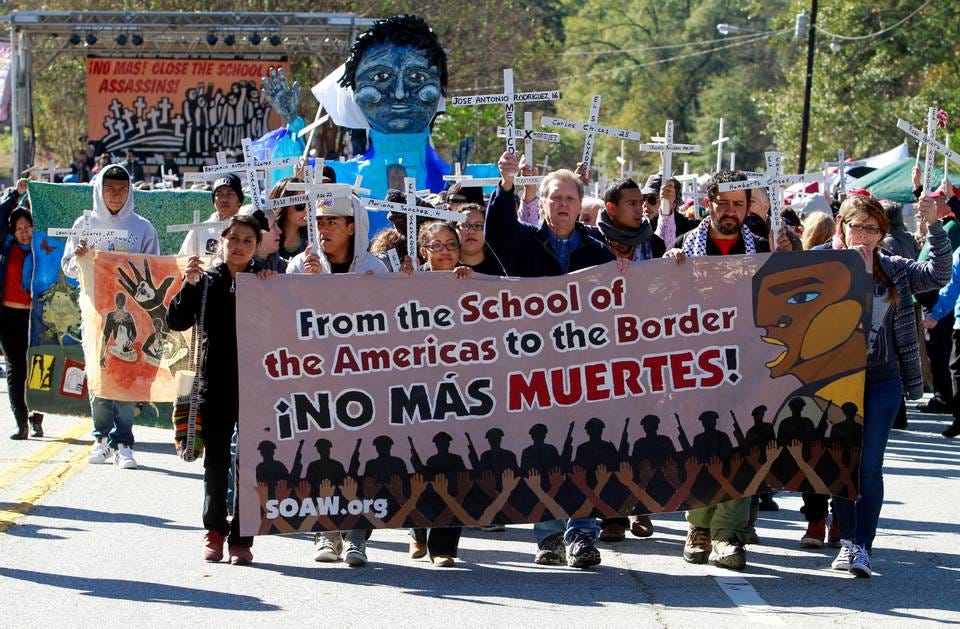

Another contentious issue in the Canal Zone: The School of the Americas run by the US Army. The volatility and violence that terrorized Central and South America during the second half of the twentieth century is very closely linked to the school’s graduates.

The School of Dictators

The original reason to start a military college in the Panama Canal Zone, where it opened in 1948, was to instill democratic values in tens of thousands of officers and cadets from across Latin America.

Instead they were trained in psychological warfare, counter-insurgency, heavy-handed interrogation techniques and other unsavory skills that could be used to steamroll Communists, wipe out indigenous peoples, and stifle others deemed a threat.

Many of Latin America’s most brutal generals, despots, junta members, and secret police graduated from the CIA-linked school. Back in their home countries — Argentina, El Salvador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Guatemala among them — they became notorious for torture, mass executions, death squads, “disappearing” opponents, running drugs, genocide, and forced sterilizations.

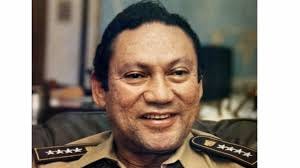

Among the alumni: Manuel Noriega.

Temperatures Rising

Through the 1950s and into the 1960s, anti-American sentiments surged as did nationalistic calls. The Americans were accused of inflicting their own culture on Panama, undercutting the local economy — low-priced goods smuggled from the Canal Zone’s commissaries hurt local stores — and instilling a militaristic mood in the country. Protests became increasingly heated as Panamanians became even more unhappy being effectively a protectorate of the United States.

Hoping to diffuse tensions, President John F. Kennedy in 1963 ordered that wherever flags were flown in the Canal Zone, the Panamanian flag should fly alongside that of the US. But that order was sometimes ignored.

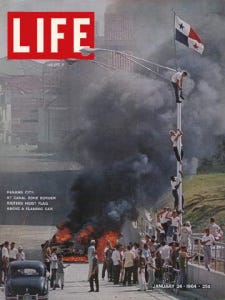

The Flag Incident

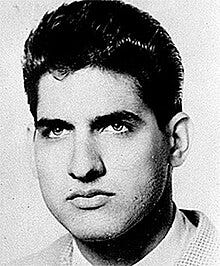

On January 9, 1964, a high school in the Canal Zone refused to fly the Panamanian flag — which was the protocol — and instead hoisted only the Star and Stripes. Panamanian students protested — and only a handful were allowed to enter the US-controlled Canal Zone where they showed up with the flag at the school.

It turned ugly: the American students and school staff verbally abused them, the flag of Panama was torn, soldiers started firing — and it spun into a riot. Twenty-one Panamanians and four U.S. soldiers died in the showdown, with hundreds injured. Panama cut diplomatic relations with the US.

The 1964 “flag incident” only galvanized anti-US sentiments and boosted nationalism — and it was deeply influential in the decision to cede the canal back to Panama.

Even after diplomatic relations were restored, the mood was frosty — all the more when the US became more deeply involved in the Vietnam War. The CIA was also using Panama as a base to run operations to try and curtail the spread of Communism, even if it meant installing oppressive leaders to do so, which did nothing to kindle warm feelings.

The Era of Military Dictatorships Begins

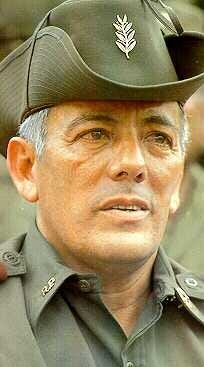

In 1968, Arnulfo Arias was again elected president; when he took office, he warned that the police and national guard were growing too powerful. Eleven days into his presidency, the head of the national guard, General Omar Torrijos, overthrew Arias in a coup d’état.

Charismatic Torrijos wasn’t as oppressive as other Latin American dictators; the general who tossed Arias was Panama’s first leader who wasn’t from the elite classes and he advocated agrarian reform; workers and the poor revered him. Nobel prize-winner novelist Gabriel García Márquez and author Graham Greene both wrote sympathetic books about Torrijos after spending time with him. For Torrijos, reducing the US presence and getting Panamanian control of the canal were key issues.

However, he wasn’t an angel: Torrijos tapped Manuel Noriega as his head of intelligence and Noriega had a knack for making problems and trouble makers disappear.

Its reputation tainted by the Vietnam War, which finally ended in 1975, the United States was condemned as being imperialistic in Panama. American analysts, including Henry Kissinger, feared that anti-US protests would spawn fresh rebels, perhaps even spread Communism. What’s more, operating the US military bases in Panama cost some $250 million a year.

In a conciliatory gesture, President Jimmy Carter began talks with Panama about ceding control of the canal to the country where it was located. In 1977, he signed the two treaties with Torrijos. Conservatives and hawks in the US have been howling ever since, but most Panamanians were elated.

The Main Points of the Panama Canal Treaty of 1977

The agreement relinquished US control over the canal by the year 2000 and guarantees its neutrality.

1. Transfer of the Canal

The US would hand over full control of the Panama Canal to Panama by December 31, 1999 — and the entire Canal Zone would be fully transferred to Panama. This ended nearly a century of U.S. sovereignty over the zone.

2. US Military Presence and Defense Role

The US would shut down its many military bases in Panama by 1999, but retained the right to defend the canal’s neutrality even after that date.

The US could also intervene militarily if canal operations or neutrality were threatened, which is what Trump appears to be arguing.

3. A Separate Canal Neutrality Treaty (Signed the Same Day) ensured that the canal remain open to all nations — Panama could not deny access to any country unless in wartime.

The treaty also came with handshake promises that Torrijos would move the country away from military dictatorship and towards democracy.

Noriega was opposed to that idea.

Rich Snitch: the Rise of Noriega

As head of military intelligence, Noriega knew lots about everybody — and he was happy to spill beans as he had been for decades. Starting in the late 1950s, the CIA paid him hefty amount to kept them up to date on Fidel Castro in Cuba; Noriega was also selling US secrets to Fidel. He also got involved with trafficking cocaine and arms, as well as making cash payments to whoever the CIA wanted to get money to.

When Torrijos perished in a mysterious plane crash in 1981, some said it was the CIA. But Panamanians widely believed it was Noriega — who soon filled Torrijos’ shoes. They weren’t a good fit.

During Noriega’s rule in the 1980s, Panama became increasingly unstable, both domestically and in its relationship with the United States. “All the young people who could get out went to a university in the States,” recalls Cahill. “It was a very rough environment — at night, you never went out alone, without a group of friends.” People were fed up; protests were constant.

“Towards the end, a lot of us were part of a movement called Cruzada Civilista — the Civilian Crusade — and went to Washington, lobbying for the United States to do something, because it was getting really bad,” says Cahill. “There were big movements of arms and drugs, lots of money laundering — and banking went down the drain. Bank of America and Chase Manhattan packed up and left.”

Once a valuable U.S. ally, Noriega was on thin ice with the US. In his 1997 memoir America’s Prisoner, Noriega said it started when he refused to work with Oliver North — as part of the CIA’s covert Iran-Contra operations to arm the Contras, the rebels fighting the Communist Sandinista government in Nicaragua; Noriega backed the Sandinistas and refused to participate.

Another issue: the US wanted to keep running the School of the Americas in Panama — despite the treaty’s clause about shutting down all US military facilities. In 1984, Noriega told them to shut down the School of the Americas — immediately.

In 1985, opposition leader Hugo Spadafora — who’d repeatedly accused Noriega of drug trafficking — was abducted and decapitated by Noriega’s forces, his corpse wrapped in a US Postal Service mail bag.

Flipping Off Uncle Sam

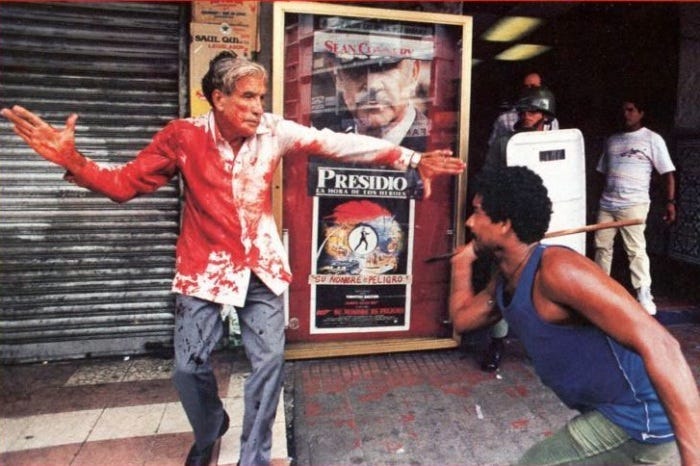

Reports of Noriega’s deep involvement in drug trafficking and money laundering — once tolerated, if not facilitated, by U.S. intelligence — became impossible to ignore. His grip on power tightened through violent crackdowns — including via a goon squad called The Dignity Battalions. And during the 1988 presidential campaigns in the US, Noriega kept saying he had “something on Bush'' — although what he was referring to has never been revealed.

Noriega wrote in his book that the US government offered him $2 million — and asylum in a third country with his family — if he’d just step down from power and onto the plane they had waiting. He refused.

The US, he said, was trying to place a candidate in the 1989 elections. When that candidate won, Noriega invalidated the presidential election results. He began baiting the US in his public speeches.

On December 15, Noriega declared war on the United States. The next day Noriega’s security forces killed an unarmed US Marine. And on December 20, the skies over Panama filled with US war planes and paratrooper-filled helicopters; more troops poured out from war ships, with 26,000 troops deployed to take down one man.

“They blanketed the isthmus,” says Cahill. “The US unleashed all the toys. Stealth fighters, stealth bombers, Apache helicopters. It was the first time a Humvee was in war. Very futuristic.”

Over the next few days, at least 500 Panamanians died, including hundreds of civilian, and 23 American soldiers were killed in action.

“The US was thinking we’ll just go in there and get Noriega and come back out,” says Cahill. “Well, that was not the case, because Noriega hid.” Four days later Noriega surfaced — at the Vatican Embassy in Panama City, where he was granted asylum.

So the US set up speakers and more speakers, surrounding the embassy with them. And they blasted Noriega out of the embassy with high-decibel rock-and-roll. “You Can Run, But You Can’t Hide,” "Welcome to the Jungle," by Guns N' Roses, "Wanted Dead Or Alive," by Bon Jovi, and “Refugee” by Tom Petty were among the selections.

“When that happened, the country erupted,” recalls Cahill. “It was like a concert. It was so loud. And then they put in heat lamps and they cooked the embassy. Those guys were sweating in there. The air conditioner units melted down.”

On January 3, 1990, not long after hearing “I Fought the Law (and the Law Won),” Noriega emerged — in full regalia, wanting to surrender to an officer as a prisoner of war. But as he walked out, a black car raced up, DEA agents ran out and tackled him to the ground.

The capturing officer made him don a dirty t-shirt for his mug shot — and he was jetted off to Miami when he was found guilty of drug running, racketeering, and money laundering and sentenced to 40 years.

A New Era Sans Military

With Noriega gone, Panamanians voted in a new president, and set upon rewriting the constitution. The country soon abolished the military — now one of the few places in the world without a standing army.

After that, Panama began prospering. Now it’s like a little Dubai, says Cahill.

Until recently, the United States has taken mostly a hands-off approach to Panama, despite its strategic importance.

Panama has flourished since gaining full control of the canal in 1999, rising as a major financial hub and trade center. Its reputation was tainted, however, following the 2016 release of the Panama Papers, exposing how the country’s lax regulations enabled tax evasion and money laundering on a massive scale.

Despite this, Panama’s economy is going gang-busters, fueled by banking, logistics, a booming real estate sector, and tourism. The expanded canal has doubled its capacity, reinforcing its role as a cornerstone of global commerce with more than $270 billion worth of cargo passing through annually.

While Trump’s claims about China controlling the canal are false and his concerns may be exaggerated, he has undeniably put Panama back on the global radar — and it’s only helped tourism, which is soaring to new heights. Cahill says, thanks to Trump’s spotlight, his business is booming.

good stuff!

Essential reading.